What do we really value? Rethinking our approach to education at UM in the age of GenAI

As part of an EDLAB research fellowship, Robyn Ausmeier spoke with UM staff and students about how they’re using GenAI in their teaching and learning. Their experiences reveal not just practical insights but also deeper questions about creativity, assessment, and the role of educators.

In this article, she reflects on the lessons learned, the ongoing challenges, and what these insights reveal about the values at the core of UM education.

Two years of GenAI at UM: what have we learned?

It is now over two years since the public release of ChatGPT-3.0 in November 2022. Moving beyond the initial waves of panic and uncertainty, we have reached a fitting time to reflect on what we have learned from the increased presence of GenAI at Maastricht University. It is clear to everyone that GenAI is here to stay and that this technology will continue to necessitate changes in higher education. However, what is less clear, is how we can better respond to the changes brought about by AI going forward.

As part of an EDLAB research fellowship, in August 2023 I began researching the ways in which UM staff and students engage with GenAI in their teaching and learning practices. The focus of the project was specifically on use cases and I conducted in-depth interviews with staff and students who are actively using GenAI.

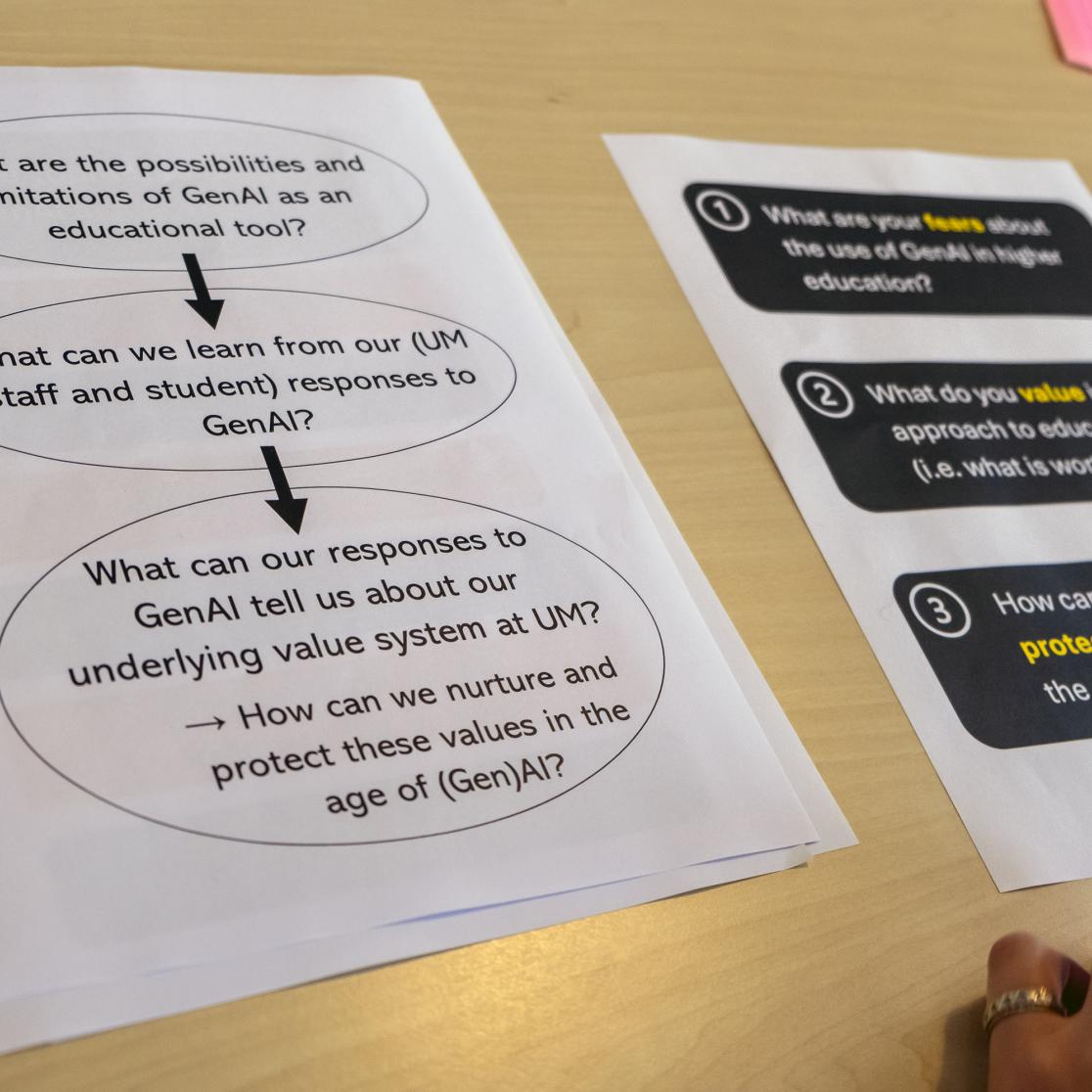

Going into this research, I intended to shed light on the limitations and possibilities of GenAI as an educational tool at UM, but ultimately I found myself more interested in what our collective and individual responses to GenAI can tell us about the values we believe to be at the heart of higher education.

Responding to uncertainty

As with the sudden moves to online and hybrid education following the COVID-19 pandemic, responses to GenAI were initially emergency measures and had to be adopted with haste. This meant that, for most of us, there was limited time to adapt and learn about the tools. Assessments had to be quickly rethought to become more ‘GenAI proof’ and to limit (uncritical) use of GenAI in final assignments, and classroom discussions were notably altered. For example, one staff participant observed that as GenAI became more widely embraced, some students began using these tools to answer the learning goals. As a result, she noticed that class discussions became more surface-level, where the students’ answers began to sound increasingly alike. While using GenAI as a critical companion or a thinking partner can be a useful tool for learning, its uncritical adoption raised concern amongst the participants.

With these changes, staff and students inevitably encountered a lot of uncertainty. When asked about responses to this uncertainty, one of my staff participants, an early adopter of GenAI, said he had observed three stages in the staff responses: denial, resistance, and then (often reluctant) action. He commented that “GenAI was the giant elephant in the room” and that it was only necessity that led to a reaction. Another participant reflected that in academia we tend to be slow in adapting to change, as opposed to in industry. Having worked in both, she observed that in academia there is a greater fear of change, and instead of taking a chance on something new, academics often stick with what is ‘good enough’ or ‘tried and tested’.

While participants raised valid reasons to be sceptical regarding the growing use of GenAI (including copyright concerns, AI bias, and the environmental toll, among others), I see this as motivation to further engage in the discussion, not to shy away from it.

Unpacking our fears

From the staff interview responses, there were mixed feelings about the increasing use of GenAI in educational settings. Some participants were excited about the potential of GenAI to enable new learning opportunities, while others highlighted the possible risks and negative impact of GenAI on higher education.

Loss of creativity and originality

One of the main fears expressed by staff participants was that GenAI use would lead to a decreased quality of education, where there is less creativity and originality in student output due to an over-reliance on GenAI tools. For example, one participant said his main fear was that students would not learn to develop their own academic voice, and would instead rely on the formatting and language offered by GenAI. He said that this was something he had already started to notice in students’ work, where the structure and writing style were becoming increasingly uniform, especially in Humanities subjects, where it is not just about what you write, but also how you write.

The changing role of educators

Another fear was that the role of educators could be fundamentally challenged, and that their value could be undermined by the introduction of GenAI tools in higher education. This was highlighted in an experience shared by a younger tutor, who spoke about a class assignment where students were allowed to use GenAI. She expected the students to still ask her questions, as they usually did, but noticed that this didn’t happen. Reflecting on this, she said it made her feel easily replaceable, and she began questioning the value of her work. However, it also helped her to recognise the unique skills she could still offer, such as interpersonal communication.

Are shortcuts replacing learning?

Thirdly, there was a fear that the learning process would be compromised by GenAI usage, with these tools being used to take shortcuts and replace the work instead of augmenting it. From the student interviews, these fears took a different form. While some did express their concerns that educational quality would be diminished, the two main fears were that they would be incorrectly accused of AI fraud, or that their education might not adequately equip them for a future of work where AI is central. However, it is also important to note that this differed largely depending on the faculty, with one participant from FSE stating he felt empowered to use GenAI in his classes, while two students from FASoS expressed their uncertainty about how (and if) they should use GenAI for learning purposes.

Ongoing concerns

From these insights, there were a few clear differences between the staff and student perceptions, as well as points where they converge. Major fears expressed by both groups concerned assessment, yet the cause of the fear differed (for staff, the decreased work quality and potential fraud cases, and for students the fear of false allegations and insufficient training on GenAI). In both groups the experiences and perceptions of GenAI were largely heterogeneous, ranging from those staff and students who were very cautious about GenAI use, to those who fully embraced it. Even though my participants were all actively engaging with GenAI themselves, and were therefore more open to its potential, they still expressed concerns about the ongoing effects of GenAI use on higher education.

Finally, what stands out when addressing the fears of both staff and students, is that there is a general atmosphere of mistrust, where students are often assumed to be guilty before proven innocent. Many of the staff fears clearly assume that students will uncritically use GenAI and that they are not also motivated by a desire to learn. If we truly value community and collaboration at UM, this aspect of trust is something to address.

(Re)assessing our values

Reflecting on the abovementioned fears, I became interested in what these reveal about the core value system at the heart of our educational practice. In addressing the uncertainties, we can consider what it is that we are anxiously protecting and what we believe is worth defending.

My participants expressed a desire to protect critical and creative thinking in academia, and to recentre the importance of the learning process rather than the output, which they saw as core values of education at UM. However, the interview responses still displayed a preoccupation with assessment as a means to measure this learning process and to determine the level of creativity and originality. Considering this, what seems to remain most valued is the centrality of final assessments and educational output.

Rethinking our approach to education in the age of GenAI therefore means rethinking the place and value of assessment in our educational practice, specifically what and how we assess. If an assignment is so easily done by ChatGPT (and other GenAI tools), is this really what we want to assess? And if we truly value the learning process, how can we better assess this process and not only the output?

Time for reflection

When starting this research, I was hoping to find a set of best practices for using GenAI in teaching and learning at UM. However, the more I spoke with colleagues and explored the topic, the more I began to question what we really want and expect students to get out of their UM education.

For example, are UM’s core learning principles of Collaborative, Constructive, Contextual and Self-directed (CCCS) learning still at the heart of our education? If not, (how) can we use the disruptions caused by GenAI as an opportunity to recentre these foundational principles? Rather than emerging with a roadmap for how to better use GenAI as an educational tool, I have instead come to question the very destination toward which we are headed. Considering the current political climate in the Netherlands, where the (monetary) value of higher education is being questioned, there is an evident need for a more unified vision of what we can uniquely offer as educators and as an educational institution.

My recommendation for moving forward (with GenAI) is therefore to stop and collectively reflect on what we actually want to be the core values of our education at Maastricht University, and how we can better work toward this vision.

By Robyn Ausmeier, 2023-2025 research fellow at EDLAB, Maastricht University.

Interested in more Teaching & Learning insights?

Also read

-

Teacher Information Points at UM

UM faculties now host Teacher Information Points (TIPs) that offer local, “just-in-time” and on-demand support for teaching staff. The aim is simple: to provide help that is closely connected to day-to-day teaching practice.

-

As a teacher, how confident are you in your digital skills? Discover your capabilities in just 25 minutes

Maastricht University invites all teaching staff to take part in the Jisc Discovery Tool pilot to explore your digital strengths.

-

UWC Maastricht students get a taste of education innovation at EDLAB

On 21 October 2025, EDLAB hosted students from United World College Maastricht for the second year in a row, as part of their Youth Social Entrepreneurship programme.