Solo l’Italia? Gabry Ponte’s Eurovision song underlines striking limitations to Italy’s effective control over its cultural heritage imagery

The staging of San Marino representative’s performance during Eurovision might be in violation of Italian cultural heritage law – yet, the principle of territoriality prevents Italy from taking effective legal action.

The 2025 Eurovision Song Contest

The Eurovision Song Contest represents a celebration of cultural identity through joyful and creative artistic expression, as each spring representatives from 52 participating countries perform their original songs on stage. As one could expect, the competition is not insulated from political tensions and controversies: this year, in particular, Israel’s participation to Eurovision was the subject of harsh criticism, with Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez explicitly calling for this state’s exclusion from the contest. At its chore, however, the competition remains a moment of international convergence around traditionally over-the-top performances. This spirit was perfectly embodied by this year’s representative for San Marino, Italian DJ Gabry Ponte, who competed with a song titled “Tutta l’Italia” (All of Italy). While Mr Ponte acknowledged the peculiarity of representing another country, and with a song “dedicated” to Italy no less, the Eurovision rules do not prohibit such instances, and “Tutta l’Italia” made its way to the big final, on Saturday 17 May 2025.

The performance

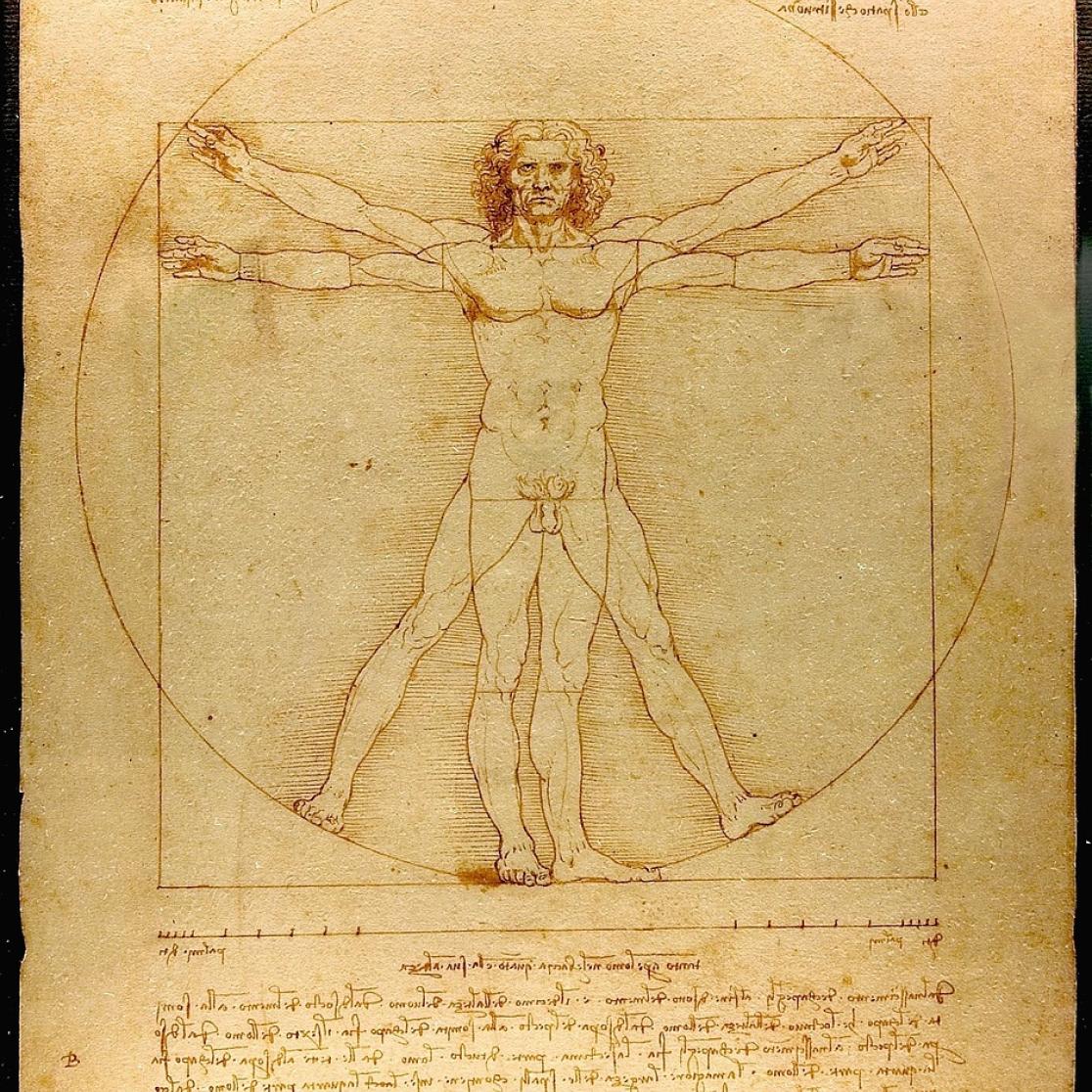

Unlike the other performers, Gabry Ponte faced a specific challenge: as a DJ, he could not rely on spectacular choreography or vocal virtuosity to meet the trademark camp standards the Eurovision public has come to expect. Nevertheless, the staging of his performance captivated the audience with a series of powerful visuals that framed Mr Ponte, his vocalists and two live musicians throughout the song. As the accordion and the tambourine played the first notes, Michelangelo’s David emerged from the screens behind the stage and began to emphatically chew some fluorescent pink gum. Cue the flame machines, the chorus, some quick fireworks, and then, to accompany the new verse, a new image: Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. The drawing was then encapsulated in a €1 coin, which was tossed into the Trevi Fountain (echoing the lyrics: e quante monetine, ma i desideri son degli altri/how many coins, but the wishes belong to someone else). Finally, the video showed, in the following order: the Colosseum, The Creation of Adam from the Sistine Chapelle, and Atlas holding the Globe, enclosed by a semicircle of columns with Corinthian capitals.

The protection of cultural heritage

These visuals emphasise the overall vibe of the song, which is markedly nationalistic – but not sovereignist – and relies on a series of Italian clichés: la mamma, spaghetti, the Mona Lisa, football, fashion, food and Craxi. Differently from these elements, however, the Italian cultural heritage imagery that was projected on the background during Mr Ponte’s performance is protected by law. Articles. 107-109 of the Codice dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio (the Italian cultural heritage law) subject the reproduction of cultural goods in public collections to the previous authorisation of the museums or institutions in their possession, against the payment of a fee. While Art. 108 provides for an exception for creative uses, and for the promotion and valorisation of the Italian cultural heritage, this only applies to non-profit-making activities. This raises the question: did the artistic team of Gabry Ponte obtain the prior authorisation of the Italian institutions for the creative use of the cultural heritage imagery?

Previous controversies

To answer this question, we reached out to Gallerie dell'Accademia di Venezia and Galleria dell'Accademia di Firenze which hold, respectively, the first two images that appear on screen, Michelangelo’s David and Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. The museums replied that they never received any authorisation request. Mr Ponte’s artistic team’s choice to pick these two artworks is particularly striking in light of recent case law that specifically targeted their unauthorised use(s). In 2017 the Florence tribunal ordered a travel agency to stop using the David to promote its tours; in 2023, the same tribunal condemned Condé Nast (editor of GQ Italy) to pay damages for a cover of model Pietro Boselli posing as the David. In 2022, the Venice court of appeal ordered German toy manufacturer Ravensburger to stop selling puzzles depicting the Vitruvian Man. Perhaps inadvertently, “Tutta l’Italia” visuals thus brought to the stage two of the most litigated images from the Italian cultural heritage.

Territoriality

The legislation in question is, in itself, rather controversial, and is often criticised by legal scholars, especially for its overlap with copyright law and the possible encroachment on the public domain. The issue has been discussed in several academic fora (most recently, at Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore; we also refer you to an upcoming conference at University of Florence). According to the relevant case law, which goes well beyond the few cases mentioned here, Italian courts have adopted a progressively expansive approach to the application of Articles 107–109. This regime however took a hard hit in 2024, when Ravensburger decided to challenge the Italian judgment before a German court. The Venice Court of Appeal had in fact ordered the cessation of production and the withdrawal of all the existing puzzles from the market, both in Italy and abroad, basing these extraterritorial effects on the “universal vocation” of the Italian cultural heritage law. The German tribunal, on the contrary, excluded that Articles 107–109 could apply outside of the Italian territory. Not only did Italy’s immunity defence fail, but so did its legislation, falling under the principle of territoriality.

Limited protection

At the basis of the expansive interpretation of Articles 107–109 lies the concern for disrespectful and debasing uses of imagery that belongs to the Italian cultural heritage. Cultural goods are therefore given personality rights, which are exercised on their behalf by their institutional custodians. As noted elsewhere, in its current form this approach lends itself to unclear standards and unnecessarily protective legal stances. The Ravensburger case highlighted the possible short circuits caused by this regime, which ended up banning a perfectly fine instructive puzzle from commerce. It also exposed the ineffectiveness of an overly restrictive system that cannot be enforced beyond State borders.

Now, Gabry Ponte’s provocative use of that same imagery further reveals just how limited the reach of Articles 107–109 truly is. We might go as far as to presume that, if the Galleria dell'Accademia di Firenze had a problem with GQ’s choice to have a handsome model pose as the David, they might also object to an animation that makes him chew and explode pink gum all over his face (despite Reddit user autistic_girl_autumn’s comment that “the imagery of the statue chewing gum sold this performance for me”). Nevertheless, since the Eurovision was broadcasted from Switzerland (just across the Italian border), it remained beyond the Italian judge’s reach. Supreme irony: were Gabry Ponte to perform “Tutta l’Italia” again in San Marino, he could use the same visuals with impunity within the very heart of the Italian State.

Conclusions

It is a rare thing being able to see so clearly the limits of a piece of legislation. It is even more unique to have them broadcasted on a global stage, in between a French ballad and an Albanian banger. Perhaps such excentric display might provide a normative push to amend an overprotective regime that, most likely, can govern… solo l’Italia (only Italy).

L. Solaro

Livia Solaro is a Ph.D. researcher at Maastricht University's Law Faculty. Under the supervision of Prof. Lars van Vliet and Prof. Marta Pertegás Sender, her research investigates restitution of Nazi-looted art, with a focus on the litigation taking place in the US.

-

Object- and Problem-Based Learning (OBL & PBL): A Fruitful Amalgamation for the Development of Legal Education

Patrons at the Arthur W. Diamond Law Library at Columbia University (USA) can encounter a duplicate of an automobile wheel that relates to the 1916 court case heard by Judge Benjamin Cardozo in MacPherson v. Buick Motor Co. The wheel is an object that hangs on a wall on the fourth floor of the...

-

The Legal Philosophy of Role-Playing Games

In this blog, Michele Ubertone aims to show that the cognitive and rational skills that are involved in role-playing are also at the heart of legal practice. Cognitive developments we all go through in the early stages of our lives, train and develop a distinctive cognitive ability, a form of...

-

Academic Curiosity in the Realm of the Law

Legal science evolves in many ways. Academic curiosity is an important drive in that evolution, opening paths of exploration and igniting awareness on the needs of society. Curiosity–in all its forms–deals with exploring, discovering, and learning towards acquiring new knowledge. Its etymology...