The Legal Philosophy of Role-Playing Games

In this blog, Michele Ubertone aims to show that the cognitive and rational skills that are involved in role-playing are also at the heart of legal practice. Cognitive developments we all go through in the early stages of our lives, train and develop a distinctive cognitive ability, a form of rationality that is intrinsic both to law and to literature.

You Wake Up in The Middle of the Night…

You wake up in the middle of the night. You hear screams coming from the street. You get up. You are still in your pyjamas. You look out the window. You see nothing. The usual Bouillonstraat, the law school in front of you, the red garbage bags that someone put out on the wrong day and nothing else. You go back to bed, when you hear that voice again. It is female voice, and this time you distinctly hear the word 'Help'. You decide to put on your slippers and go down to the street to get a better view. You take your phone with you, it is 3.47 am. You already dial 112, but you don't initiate the call. As you look around, the door inexplicably closes behind you. You have no keys. How could you be so stupid? Now you are on the street in your pyjamas and slippers with your phone in your hand. What do you do?

This could be the beginning of a role-playing game session. In this case, I was the Game Master, and you were invited to act as a player. A role-playing game is a type of game in which participants assume the roles of fictional characters in a jointly created world. The game is run by a narrator, or Game Master (GM), who controls all aspects of the world that do not depend on the character's decisions: past events, natural phenomena, the geography of the world, etc., as well as the decisions of all non-player characters (NPCs). But all the rulings that the Game Master makes about the world are based on the demands of the players.

In this case, for example, you may ask how the door of your building that was just shut behind you looks like, or if there is someone you know in the building that you may feel comfortable calling. These aspects of the world didn’t exist before you asked these questions. But the role-playing game creates a system of rules that allows to determine in a reasonably objective manner how the world will respond to the player’s demand. There are infinite choices you can make: you may decide to run to the police station, to call a friend, to break a glass of a window of the Faculty of Law to go hide in an office or lecture room… Whatever you decide to do the role-playing game has some rule, procedure or ritual that defines what will happen. There may be dices to roll or it may be for the Game Master to decide. But as the players make decisions, as dice rolls are made, as the Game Master has made his or her rulings, a whole virtual world starts to emerge.

The characteristics of the player characters (PCs) and the world are partly defined by the players or the GM, and partly constrained by the rules of the game. Players interact with each other and the game environment through verbal narration. Rules, dice rolls, and previous decisions made by the players and the GM partially pre-determine the consequences of the players' actions. This gives internal coherence and objectivity to the imaginary world in which the story takes place and limits the GM's discretion.

In what follows, I will attempt to show that the cognitive and rational skills that are involved in role-playing are also at the heart of legal practice. In doing so, I am following an old and noble tradition, that of lawyers who, tired of talking about statutes and regulations, decide, for no apparent reason, to try to find far-fetched excuses to talk about something less boring than law. This is sometimes perceived like a solipsistic divertissement, a sort of exit strategy from the boredom of legal science, and something which is only useful to the amusement of the person who engages in this exercise but of little or no interest (scientific or otherwise) for everyone else. The most famous case is that of Law and Literature. But there are many others. The comparison between the judge and the historian. The comparison between and legal and musical interpretation. Sometimes these kinds of operations seem sterile or far-fetched, but I would like to present an argument to convince you otherwise.

Role Play as a Basic Cognitive Ability

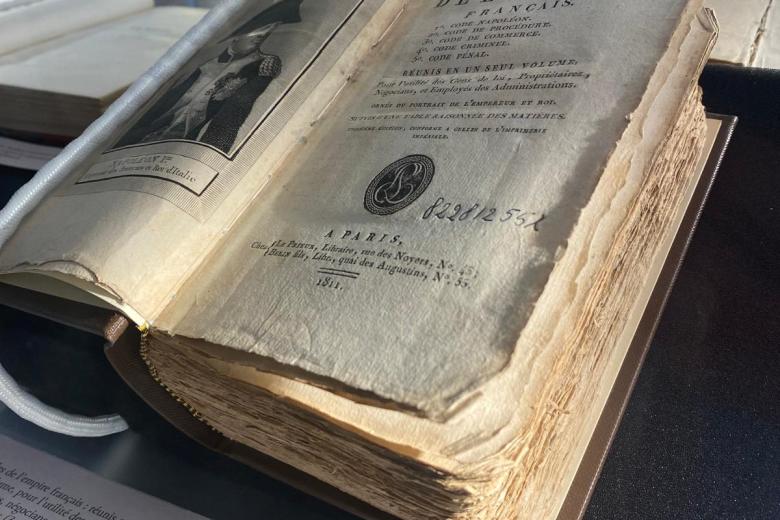

The concept of role-playing became institutionalised in the 1970s with the invention of Dungeons and Dragons, but in reality, it is based on much more ancient practices and intuitions, present in many different activities fundamental to the development of human culture.

According to Jean Piaget, in the cultural and social development of the child, play has a fundamental function. There are three types of play that the child must necessarily go through in order to develop in a healthy way, in which the child’s way of playing progressively develops.

The first phase that starts with birth is characterised by sensorimotor play: this consists in starting to use objects creatively as tools. It is in this phase that children develop the ability to recognise “affordances”, i.e., physical properties that allow objects to obtain certain desired effects or to perform certain desired functions. For example, a child of this age may like to play with the house keys, learning how they can make different types of sound when they are shaken.

In the second phase, starting at 18 months of age, children enter the phase of what is called symbolic play. In this case, children start to be interested in objects and people not merely in virtue of their physical properties, but in virtue of their symbolic properties. This is when children start to pretend that a pen is a phone or to pretend that the house dog is a dragon or that their bed is pirate ship or they themselves are princesses or policemen.

This is when role play proper begins and when children start to interpret the world not only in terms of physical functions, but in terms of what John Searle calls “status functions”. Status functions are the building blocks of social reality. A status function is a function that an object or person can perform not in virtue of its physical structure but in virtue of the symbolic value it is attributed.

A good way to explain this distinction is to compare a wall and a border. Both a wall and a border have the function of delimiting territory, but while the wall performs this function thanks to its physical structure, a border performs its function merely through the recognition of its status, i.e., by being recognized as a border.

This symbolic phase is one of intense role playing and it is necessary to lead to the third and final phase, games with rules. Only after understanding the normative symbolic value of physical objects children develop the ability to attribute symbolic or normative value to abstract entities like rules, points, powers, bonuses, rights, and obligations.

A Distinctive Type of Rationality Involved in Role-Play and its Connection to Law

This cognitive development we all go through in the early stages of our lives trains and develops a distinctive cognitive ability, a form of rationality that is intrinsic both to law and to literature. I will try to explain what this rationality consists of with the word of John Ronald Ruel Tolkien, the author of the Lord of the Rings. The quote is taken from a 1938 essay titled On Fairy Stories.

“What really happens is that the story-maker proves a successful 'sub-creator'. He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is 'true': it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside. The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather art, has failed. You are then out in the Primary World again, looking at the little abortive Secondary World from outside.”

We can see Piaget’s development of play as a transition from the Primary World to the Secondary World. While the sensorimotor phase of play is totally located and understandable in terms of the physical properties of the Primary World, the second phase, the Symbolic phase, where children start to role play is somewhat liminal: it is located somewhat in between the two worlds. Children are interacting with fictional entities (like a pirate ship or a dragon) but these always have a one-to-one correspondence to properties of physical entities (like the child’s bed which represents the pirate ship or the house dog which represents a dragon). In the final phase, the phase of games with rules, some elements of the game are abstract, they don’t have any correspondence to the physical world, they only exist in virtue of being mentally represented. The final phase is characterised by elements that are fully located in the Secondary World, elements like violations, rounds, points and obligations.

I believe that the type of rationality that is developed through roleplay, especially in the second phase, is essential to the type of intelligence that is required to the good lawyer. Intelligence is often defined as the ability to solve problems, the ability to select the most efficient means to achieve given ends. This is a fundamental aspect of intelligence; it is what is called “instrumental rationality”. But I think that this is not the fundamental skill that we as lawyers should be training.

The cognitive skill that constitutes the common ground between legal practice and role-play can be termed "hermeneutic rationality," which is in some sense the opposite of instrumental rationality. While instrumental rationality focuses on finding the appropriate tools to achieve predefined ends, hermeneutic rationality involves the ability to define ends that can be reached with the available tools. This distinction is crucial for understanding the broader cognitive and social benefits of role-play.

Let’s go back where we began. You are in front of your door, in Bouillonstraat, with a potential killer hiding in the vicinity… What do you do? In order to answer this question, you have to ask the Game Master questions. What do I see around me? Is there anyone? Can I see any light coming from behind the windows in the street? Do I have any friends I can call? By asking these questions, you interpret and complement the Secondary World. The right questions start with an acknowledgement of the elements of the Secondary World that can be inferred by the story so far, and consist of developing these elements in a way that makes sense from a narrative point of view.

I think what lawyers are doing is not much different from that. In saying this I am not saying anything particularly new. I am just adapting a very famous metaphor put forward by Ronald Dworkin. Ronald Dworkin's comparison of law to a chain novel is a central theme of Dworkin’s legal philosophy, and particularly of his theory of legal interpretation. Dworkin develops this comparison in his book "Law's Empire", where he argues that the process of judicial decision-making is akin to a group of authors writing a novel in sequence, each building upon the chapters written by their predecessors. In this metaphor, each judge is both an author and a critic, tasked with interpreting and continuing the narrative in a way that maintains coherence and integrity with what has come before. Dworkin emphasises that judges should not merely find or invent meanings but should aim to create a single, coherent narrative that fits and justifies the legal principles established by previous decisions.

I think it is this collaborative world building that constitutes the fundamental common ground between role-playing and law.

M. Ubertone

Main research interests:

- Legal argumentation

- Evidence (expert evidence, fact-law distinction)

- Law and language (semantic externalism, division of linguistic labor)

- Law and cognitive science (extended mind, division of cognitive labor)

-

Object- and Problem-Based Learning (OBL & PBL): A Fruitful Amalgamation for the Development of Legal Education

Patrons at the Arthur W. Diamond Law Library at Columbia University (USA) can encounter a duplicate of an automobile wheel that relates to the 1916 court case heard by Judge Benjamin Cardozo in MacPherson v. Buick Motor Co. The wheel is an object that hangs on a wall on the fourth floor of the...

-

Solo l’Italia? Gabry Ponte’s Eurovision song underlines striking limitations to Italy’s effective control over its cultural heritage imagery

The staging of San Marino representative’s performance during Eurovision might be in violation of Italian cultural heritage law – yet, the principle of territoriality prevents Italy from taking effective legal action.

-

Academic Curiosity in the Realm of the Law

Legal science evolves in many ways. Academic curiosity is an important drive in that evolution, opening paths of exploration and igniting awareness on the needs of society. Curiosity–in all its forms–deals with exploring, discovering, and learning towards acquiring new knowledge. Its etymology...