Should a trade mark owner be able to stop others from marketing the same product after removing the trade mark?

Most people’s gut-feeling would say yes… because it sounds unfair. The CJEU also opines yes, but bends EU trade mark protection rules considerably and thereby increases EU trade mark protection for trade mark proprietors regarding two aspects: 1) the scope of when a sign is used in the course of trade, and 2) the scope of the right of first marketing.

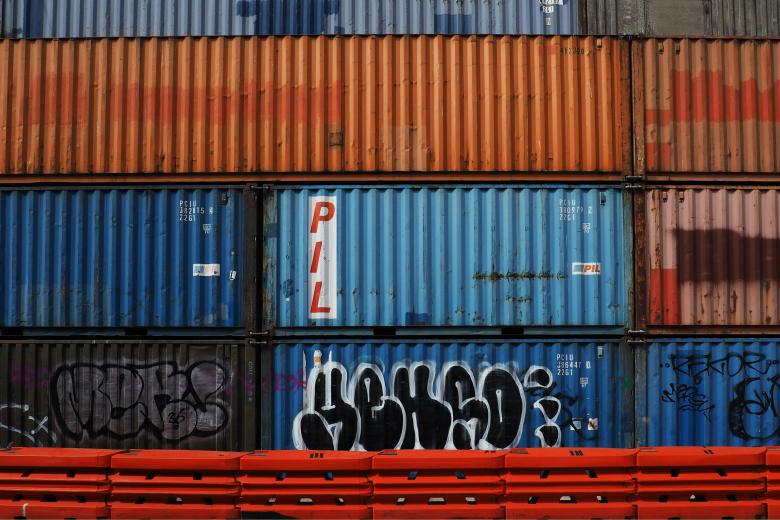

In the case at hand (C-129/17), Mitsubishi, one of the major market players in forklift trucks, markets these trucks under their trade mark MITSUBISHI in several countries in the world, among others in Asia. The Belgian company Duma and its affiliate GSI acquire such trucks in Asia and put them under a customs warehouse procedure, prior to importing them into the European Economic Area. During this procedure they remove the Mitsubishi mark (= de-branding), make the necessary modifications to render the goods compliant with EU standards and affix their own marks to the forklift trucks (= re-branding).

Use in the course of trade

It is a fundamental principle of trade mark law that a trade mark can only be infringed if a third party uses an identical or similar sign to the trade mark in the course of trade (Art. 9 Reg 2017/1001 and Art. 10 Dir 2015/2436). Looking at the facts of the case, one has to acknowledge, as did Advocate General Campos Sánchez-Bordona in his Opinion, that Duma and GSI do not “use” an identical or similar sign to Mitsubishi; to the contrary, they remove the trade mark and use their own sign, which is different from the Mitsubishi mark. Nevertheless, the CJEU finds that Duma and GSI’s active conduct of de-branding is done with a view on importing and marketing goods and therefore must be regarded as “use in the course of trade”. Such a finding is contrary to the law of EU Member States such as the UK and Germany, as the Advocate General had noted (Opinion, para. 61ff). The Court thereby considerably broadens the concept of “use” to include activities relating to the mark, e.g. de-branding, taken as a preparation of putting the goods, detached of the mark, on the market.

Exhaustion of rights

The same rationale is applied by the CJEU in the analysis as to whether the de-branding infringes Mitsubishi’s right to control the first marketing of forklift trucks bearing the mark (exhaustion of rights). Indeed, this right of first marketing relates to products carrying the trade mark, not to products that enter the market without or with another trade mark. However, the CJEU finds that the removal of the mark deprives the proprietor of this essential right because it prevents the goods from bearing the mark at first marketing (C-129/17, para. 42). Evidently, the Court does not have difficulties in broadening the scope of the right to first marketing, possibly because an amendment of current EU trade mark law (not yet applicable during this case) also broadens the scope of protection in similar situations (Art. 9(4) Reg 2017/1001 and Art. 10(4) Dir 2015/2436). Ultimately, this approach seems to favour market segmentation, arguably to the detriment of consumers.

Unfair competition

Strikingly, the legal claims brought in the national procedure focused on the right of first marketing and not on an unfair competition claim. Accordingly, it could have been argued that the general appearance of the trucks was so similar to Mitsubishi trucks (because they are the same product) that consumers are likely to be confused as to the origin of the product. In fact, during the national procedure, it had been established that consumers could indeed tell when looking at the forklift trucks, even though they did not carry the Mitsubishi mark anymore, that they looked like Mitsubishi trucks. However, this did not lead to an assessment of a possible infringement of the trade dress of the product under unfair competition rules. This may, however, have been the better avenue to stop third parties from marketing the same product without the brand, where consumers still recognize those products as being the trade mark proprietors’ goods. While the CJEU achieves the same result, it did so by broadening trade mark protection, arguably without a good justification.

| More blogs on Law Blogs Maastricht |

A. Moerland

Anke Moerland is Professor of Intellectual Property, Frontier Technologies and International Trade in the International Law Department, Maastricht University. She holds a PhD on Intellectual property protection in EU bilateral trade agreements from Maastricht University.

-

The way to Geneva and INC-5.2 after the IACtHR Advisory Opinion on the Climate Emergency and Human Rights

How might the IACtHR Advisory Opinion on climate emergency and human rights reshape the Plastics Treaty negotiations?

-

Trading Softly? The EU’s Quiet Shift Toward Clean Trade and Investment Partnerships

For decades, multilateralism has been the guiding principle for regulating international trade relations between states. The European Union (EU) has long championed this approach, firmly believing that global cooperation - ideally through consensus among all countries - is the most effective way to...

-

Rules Under Fire: The Case for International Trade Law Today

On 17 April, many of us had the pleasure of attending an IGIR Expert Lecture by John Clarke, former Chief Agriculture Negotiator of the European Union and former Head of the EU Delegation to the World Trade Organization and the United Nations in Geneva. He is currently a fellow at the Maastricht...