Facebook’s data sharing practices under unfair competition law - longread

This is a brief analysis of Facebook’s data sharing practices under unfair competition rules in the US and EU. A paper on this topic co-authored by myself and MEPLI research fellow Stephan Mulders will be available shortly, and it will be presented at the Amsterdam Privacy Conference in October 2018.

2018 has so far not been easy on the tech world. The first months of the year brought a lot of bad news: two accidents with self-driving cars (Tesla and Uber) and the first human casualty [1], another Initial Coin Offering (ICO) scam costing investors $660 million [2], and Donald Trump promising to go after Amazon [3]. But the scandal that made the most waves had to do with Facebook data being used by Cambridge Analytica [4].

Data brokers and social media

In a nutshell, Cambridge Analytica was a UK-based company that claimed to use data to change audience behavior either in political or commercial contexts [5]. Without going too much into detail regarding the identity of the company, its ties, or political affiliations, one of the key points in the Cambridge Analytica whistleblowing conundrum is the fact that it shed light on Facebook data sharing practices which, unsurprisingly, have been around for a while. To create psychometric models which could influence voting behavior, Cambridge Analytica used the data of around 87 million users, obtained through Facebook’s Graph Application Programming Interface (API), a developer interface providing industrial-level access to personal information [6].

The Facebook Graph API

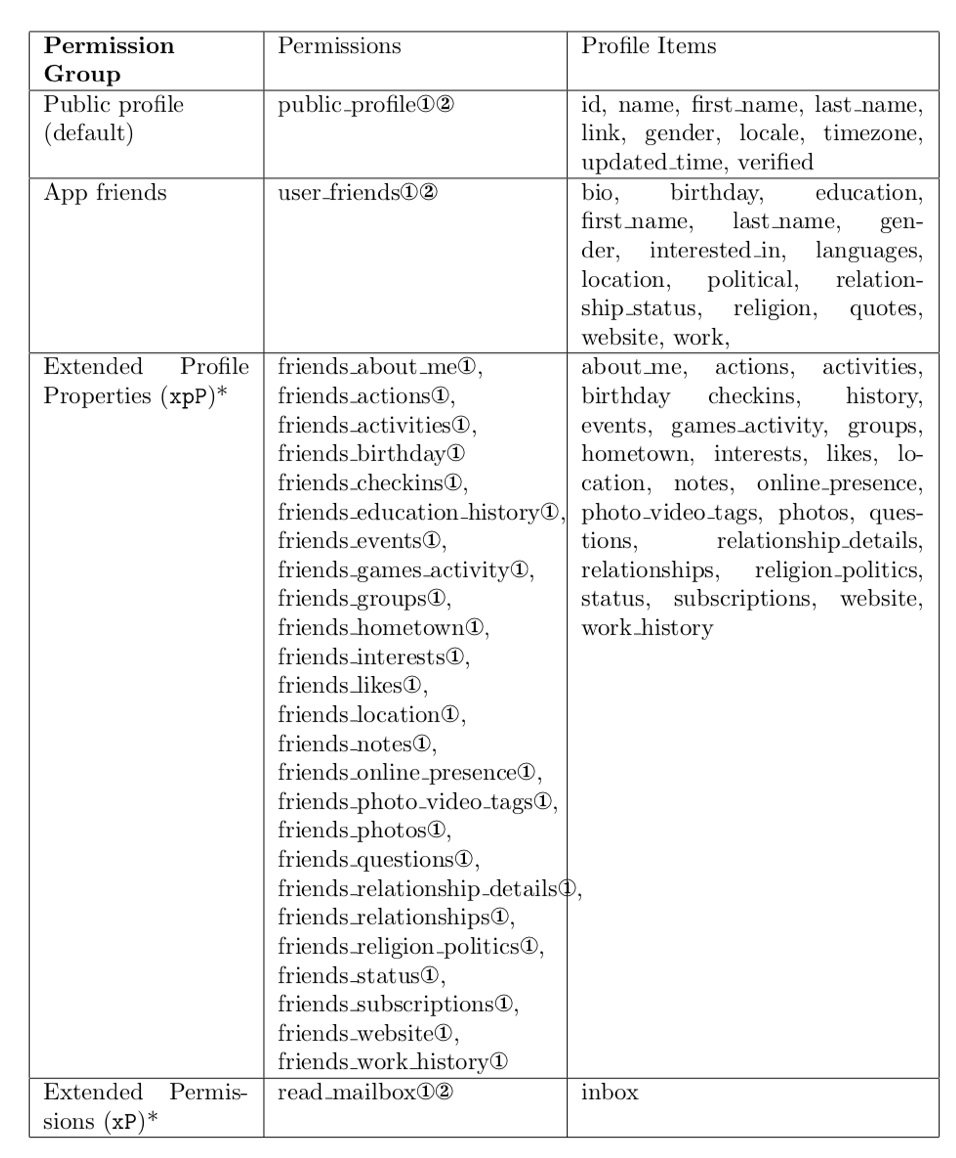

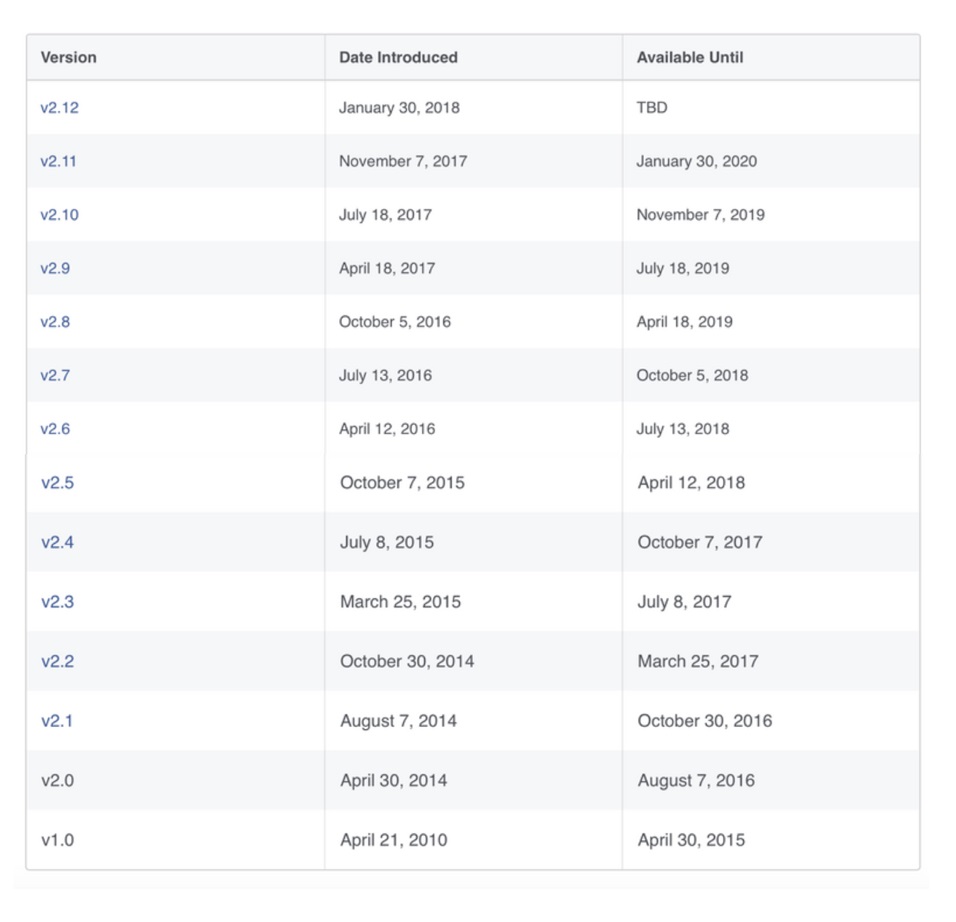

The first version of the API (v1.0), which was launched in 2010 and was up until 2015, could be used to not only gather public information about a given pool of users, but also about their friends, in addition to granting access to private messages sent on the platform (see Table 1 below). The amount of information belonging to user friends that Facebook allowed third parties to tap into is astonishing. The extended profile properties permission facilitated the extraction of information about: activities, birthdays, check-ins, education history, events, games activity, groups, interests, likes, location, notes, online presence, photo and video tags, photos, questions, relationships and relationships details, religion and politics, status, subscriptions, website and work history. Extended permissions changed in 2014, with the second version of the Graph API (v2.0), which suffered many other changes since (see Table 2) [7]. However, one interesting thing that stands out when comparing versions 1.0 and 2.0 is that less information is gathered from targeted users than from their friends, even if v2.0 withdrew the extended profile properties (but not the extended permissions relating to reading private messages).

Cambridge Analytica obtained Facebook data with help from another company, Global Science Research, set up by Cambridge University-affiliated faculty Alexandr Kogan and Joseph Chancellor. Kogan had previously collaborated with Facebook for his work at the Cambridge Prosociality & Well-Being Lab. For his research, Kogan collected data from Facebook as a developer, using the Lab’s account registered on Facebook via his own personal account, and he was also in contact with Facebook employees who directly sent him anonymized aggregate datasets [8].

The Facebook employees who sent him the data were working for Facebook’s Protect and Care Team, but were themselves doing research on user experience as PhD students [9]. Kogan states that the data he gathered with the Global Science Research quiz is separate from the initial data he used in his research, and it was kept on different servers. Kogan’s testimony before the UK Parliament’s Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee does clarify which streams of data were used by which actors, but none of the Members of Parliament attending the hearing asked any questions about the very process through which Kogan was able to tap into Facebook user data. He acknowledged that for harvesting information for the Strategic Communication Laboratories – Cambridge Analytica’s affiliated company – he used a market research recruitment strategy: for around $34 per person, he aimed at recruiting up to 20,000 individuals who would take an online survey [10]. The survey would be accessible through an access token, which required participants to login using their Facebook credentials.

Access Tokens

On the user end, Facebook Login is an access token which allows users to log in across platforms. The benefits of using access tokens are undeniable: having the possibility to operate multiple accounts using one login system allows for efficient account management. The dangers are equally clear. On the one hand, one login point (with one username and one password) for multiple accounts can be a security vulnerability. On the other hand, even if Facebook claims that the user is in control of the data shared with third parties, some apps using Facebook Login – for instance wifi access in café’s, or online voting for TV shows – do not allow users to change the information requested by the app, creating a ‘take it or leave it’ situation for users.

On the developer end, access tokens allow apps operating on Facebook to access the Graph API. The access tokens perform two functions:

- They allow developer apps to access user information without asking for the user’s password; and

- They allow Facebook to identify developer apps, users engaging with this app, and the type of data permitted by the user to be accessed by the app [11].

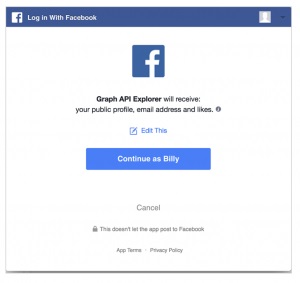

Understanding how Facebook Login works is essential in clarifying what information users are exposed to right before agreeing to hand their Facebook data over to other parties.

Data sharing and consent

As Figure 1 shows, and as it can be seen when browsing through Facebook’s Terms of Service, consent seems to be at the core of Facebook’s interaction with its users. This being said, it is impossible to determine, on the basis of these terms, what Facebook really does with the information it collects. For instance, in the Statement of Rights and Responsibilities dating from 30 January 2015, there is an entire section on sharing content and information:

| You own all of the content and information you post on Facebook, and you can control how it is shared through your privacy and application settings. In addition: |

|

(1) For content that is covered by intellectual property rights, like photos and videos (IP content), you specifically give us the following permission, subject to your privacy and application settings: you grant us a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to use any IP content that you post on or in connection with Facebook (IP License). This IP License ends when you delete your IP content or your account unless your content has been shared with others, and they have not deleted it. (2) When you delete IP content, it is deleted in a manner similar to emptying the recycle bin on a computer. However, you understand that removed content may persist in backup copies for a reasonable period of time (but will not be available to others). (3) When you use an application, the application may ask for your permission to access your content and information as well as content and information that others have shared with you.We require applications to respect your privacy, and your agreement with that application will control how the application can use, store, and transfer that content and information. (To learn more about Platform, including how you can control what information other people may share with applications, read our Data Policy and Platform Page.) (4) When you publish content or information using the Public setting, it means that you are allowing everyone, including people off of Facebook, to access and use that information, and to associate it with you (i.e., your name and profile picture). (5) We always appreciate your feedback or other suggestions about Facebook, but you understand that we may use your feedback or suggestions without any obligation to compensate you for them (just as you have no obligation to offer them). |

This section appears to establish Facebook as a user-centric platform that wants to give as much ownership to its customers. However, the section says nothing about the fact that app developers used to be able to tap not only into the information generated by users, but also that of their friends, to an even more extensive degree. There are many other clauses in the Facebook policies that could be relevant for this discussion, but let us dwell on this section.

Taking a step back, from a legal perspective, when a user gets an account with Facebook, a service contract is concluded. If users reside outside of the U.S. or Canada, clause 18.1 of the 2015 Statement of Rights and Responsibilities mentions the service contract to be an agreement between the user and Facebook Ireland Ltd. For U.S. and Canadian residents, the agreement is concluded with Facebook Inc [12]. Moreover, according to clause 15, the applicable law to the agreement is the law of the state of California [13]. This clause does not pose any issues for agreements with U.S. or Canadian users, but it does raise serious problems for users based in the European Union. In consumer contracts, European law curtails party autonomy in choosing applicable law, given that some consumer law provisions in European legislation are mandatory, and cannot be derogated from [14]. Taking the example of imposing the much lesser protections of U.S. law on European consumers, such clauses would not be valid under EU law. As a result, in 2017 the Italian Competition and Market Authority gave WhatsApp a €3 million fine on the ground that such contractual clauses are unfair [15].

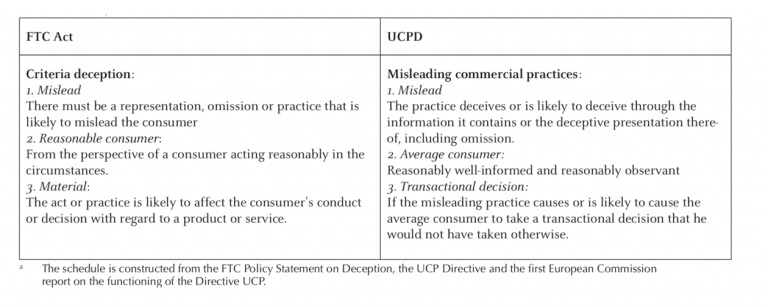

Apart from problems with contractual fairness, additional concerns arise with respect to unfair competition. Set between competition law and private law, unfair competition is a field of law that takes into account both bilateral transactions, as well as the broader effect they can have on a market. The rationale behind unfair competition is that deceitful/unfair trading practices which give businesses advantages they might otherwise not enjoy should be limited by law [16]. As far as terminology goes, in Europe, Directive 2005/29/EC, the main instrument regulating unfair competition, uses the terms ‘unfair commercial practices’, whereas in the United States, the Federal Trade Commission refers to ‘unfair or deceptive commercial practices’ [17]. The basic differences between the approaches taken in the two federal/supranational legal systems can be consulted in Figure 2 below [18]:

Facebook’s potentially unfair/deceptive commercial practices

In what follows, I will briefly refer to the 3 comparative criteria identified by van Eijk et al.

The fact that a business must do something (representation, omission, practice, etc.) which deceives or is likely to deceive or mislead the consumer is a shared criterion in both legal systems. There are two main problems with Facebook’s 2015 terms of service to this end. First, Facebook does not specify how exactly the company shares user data and with whom. Second, this version of the terms makes no reference whatsoever to the sharing of friends’ data, as could be done through the extended permissions. These omissions, as well as the very limited amount of information offered to consumers, through which they are supposed to understand Facebook’s links to other companies as far as their own data is concerned, are misleading.

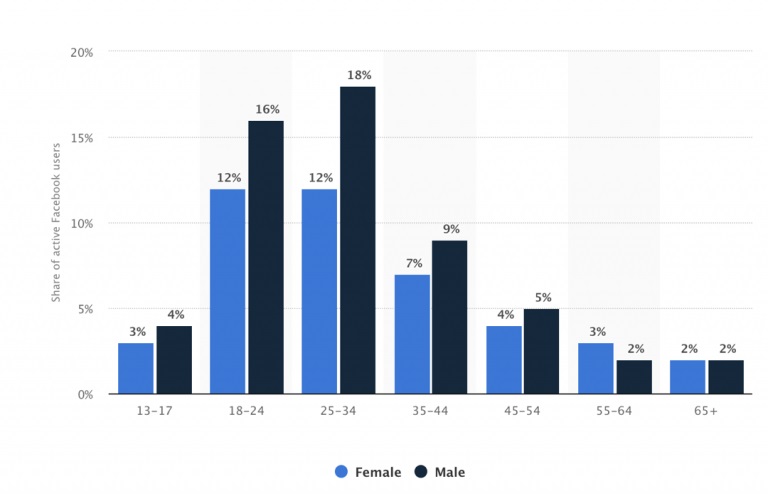

The second criterion, that of the reasonable/average consumer, is not so straightforward: the information literacy of Facebook users fluctuates, as it depends on demographic preferences. With the emergence of new social media platforms such as Snapchat and Musical.ly, Facebook might not be the socializing service of choice for younger generations. However, official statistics are based on data that includes a lot of noise. It seems that fake accounts make up around 3% of the total number of Facebook accounts, and duplicate accounts make up around 10% of the same total [19]. This poses serious questions regarding the European standard of the average consumer, because there is no way to currently estimate how exactly this 13% proportion would change the features of the entire pool of users. There are many reasons why fake accounts exist, but let me mention two of them. First, the minimum age for joining Facebook is 13; however, the enforcement of this policy is not easy, and a lot of minors can join the social media platform by simply lying about their age. Second, fake online profiles allow for the creation of dissociate lives: individuals may display very different behavior under the veil of anonymity, and an example in this respect is online bullying.

These aspects can make it difficult for a judge to determine the profile of the reasonable/average consumer as far as social media is concerned: would the benchmark include fake and duplicate accounts? Would the reasonable/average consumer standard have to be based on the real or the legal audience? What level of information literacy would this benchmark use? These aspects remain unclear.

The third criterion is even more complex, as it deals with the likelihood of consumers taking a different decision, had they had more symmetrical information. Two main points can be made here. On the one hand, applying this criterion leads to a scenario where we would have to assume that Facebook would better disclose information to consumers. This would normally take the form of specific clauses in the general terms and conditions. For consumers to be aware of this information, they would have to read these terms with orthodoxy, and make rational decisions, both of which are known not to be the case: consumers simply do not have time and do not care about general terms and conditions, and make impulsive decisions. If that is the case for the majority of the online consumer population, it is also the case for the reasonable/average consumer. On the other hand, perhaps consumers might feel more affected if they knew beforehand the particularities of data sharing practices as they occurred in the Cambridge Analytica situation: that Facebook was not properly informing them about allowing companies to broker their data to manipulate political campaigns. This, however, is not something Facebook would inform its users about directly, as Cambridge Analytica is not the only company using Facebook data, and such notifications (if even desirable from a customer communication perspective), would not be feasible, or would lead to information overload and consumer fatigue. If this too translates into a reality where consumers do not really care about such information, the third leg of the test seems not to be fulfilled. In any case, this too is a criterion which will very likely raise many more questions that it aims to address.

In sum, two out of the three criteria would be tough to fulfill. Assuming, however, that they would indeed be fulfilled, and even though there are considerable differences in the enforcement of the prohibition against unfair/deceptive commercial practices, the FTC, as well as European national authorities can take a case against Facebook to court to order injunctions, in addition to other administrative or civil acts. A full analysis of European and Dutch law in this respect will soon be available in a publication authored together with Stephan Mulders.

Harmonization and its discontents

The Italian Competition and Market Authority (the same entity that fined WhatsApp) launched an investigation into Facebook on April 6, on the ground that its data sharing practices are misleading and aggressive [20]. The Authority will have to go through the same test as applied above, and in addition, will very likely also consult the black-listed practices annexed to the Directive. Should this public institution from a Member State find that these practices are unfair, and should the relevant courts agree with this assessment, a door for a European Union-wide discussion on this matter will be opened. Directive 2005/29/EC is a so-called maximum harmonization instrument, meaning that the European legislator aims for it to level the playing field on unfair competition across all Member States. If Italy’s example is to be followed, and more consumer authorities restrict Facebook practices, this could mark the most effective performance of a harmonizing instrument in consumer protection. If the opposite happens, and Italy ends up being the only Member State outlawing such practices, this could be a worrying sign of how little impact maximum harmonization has in practice.

New issues, same laws

Nonetheless, in spite of the difficulties in enforcing unfair competition, this discussion prompts one main take-away: data-related practices do fall under the protections offered by regulation on unfair/deceptive commercial practices [21]. This type of regulation already exists in the US just as much as it exists in the EU, and is able to handle new legal issues arising out of the use of disruptive technologies. The only areas where current legal practices are in need of an upgrade deal with interpretation and proof: given the complexity of social media platforms and the many ways in which they are used, perhaps judges and academics should also make use of data science to better understand the behavior of these audiences, as long as this behavior is central for legal assessments.

References

|

[1] Will Knight, ‘A Self-driving Uber Has Killed a Pedestrian in Arizona’, MIT Technology Review, The Download, March 19, 2018; Alan Ohnsman, Fatal Tesla Crash Exposes Gap In Automaker’s Use Of Car Data, Forbes, April 16, 2018. [2] John Biggs, ‘Exit Scammers Run Off with $660 Million in ICO Earnings’, TechCrunch, April 13, 2018. [3] Joe Harpaz, ‘What Trump’s Attack On Amazon Really Means For Internet Retailers’, Forbes, April 16, 2018. [4] Carole Cadwalladr and Emma Graham-Harrison, ‘Revealed: 50 Million Facebook Profiles Harvested for Cambridge Analytica in Major Data Breach’, The Guardian, March 17, 2018. [5] The Cambridge Analytica websitereads: ‘Data drives all we do. Cambridge Analytica uses data to change audience behavior. Visit our political or commercial divisions to see how we can help you.’, last visited on April 27, 2018. It is noteworthy that the company started insolvency procedures on 2 May, in an attempt to rebrand itself as Emerdata, see see Shona Ghosh and Jake Kanter, ‘The Cambridge Analytica power players set up a mysterious new data firm — and they could use it for a ‘Blackwater-style’ rebrand’, Business Insider, May 3, 2018. [6] For a more in-depth description of the Graph API, as well as its Instagram equivalent, see Jonathan Albright, The Graph API: Key Points in the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica Debacle, Medium, March 21, 2018. [7] Iraklis Symeonidis, Pagona Tsormpatzoudi & Bart Preneel, ‘Collateral Damage of Facebook Apps: An Enhanced Privacy Scoring Model’, IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive, 2015, p. 5. [8] UK Parliament Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee, ‘Dr Aleksandr Kogan questioned by Committee’, April 24, 2018; see also the research output based on the 57 billion friendships dataset: Maurice H. Yearwood, Amy Cuddy, Nishtha Lamba, Wu Youyoua, Ilmo van der Lowe, Paul K. Piff, Charles Gronind, Pete Fleming, Emiliana Simon-Thomas, Dacher Keltner, Aleksandr Spectre, ‘On Wealth and the Diversity of Friendships: High Social Class People around the World Have Fewer International Friends’, 87 Personality and Individual Differences224-229 (2015). [9] UK Parliament Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee hearing. [10] This number mentioned by Kogan in his witness testimony conflicts with media reports which indicate a much higher participation rate in the study, see Julia Carrie Wong and Paul Lewis, ‘Facebook Gave Data about 57bn Friendships to Academic’, The Guardian, March 22, 2018. [11] For an overview of Facebook Login, see Facebook Login for Apps – Overview, last visited on April 27, 2018. [12] Clause 18.1 (2015) reads: If you are a resident of or have your principal place of business in the US or Canada, this Statement is an agreement between you and Facebook, Inc. Otherwise, this Statement is an agreement between you and Facebook Ireland Limited. [13] Clause 15.1 (2015) reads: The laws of the State of California will govern this Statement, as well as any claim that might arise between you and us, without regard to conflict of law provisions. [14] Giesela Ruhl, ‘Consumer Protection in Choice of Law’, 44(3) Cornell International Law Journal569-601 (2011), p. 590. [15] Italian Competition and Market Authority, ‘WhatsApp fined for 3 million euro for having forced its users to share their personal data with Facebook’, Press Release, May 12, 2018. [16] Rogier de Vrey, Towards a European Unfair Competition Law: A Clash Between Legal Families : a Comparative Study of English, German and Dutch Law in Light of Existing European and International Legal Instruments(Brill, 2006), p. 3. [17] Nico van Eijk, Chris Jay Hoofnagle & Emilie Kannekens, ‘Unfair Commercial Practices: A Complementary Approach to Privacy Protection’, 3 European Data Protection Law Review1-12 (2017), p. 2. [18] The tests in Figure 2 have been simplified by in order to compare their essential features; however, upon a closer look, these tests include other details as well, such as the requirement of a practice being against ‘professional diligence’ (Art. 4(1) UCPD). [19] Patrick Kulp, ‘Facebook Quietly Admits to as Many as 270 Million Fake or Clone Accounts’, Mashable, November 3, 2017. [20] Italian Competition and Market Authority, ‘Misleading information for collection and use of data, investigation launched against Facebook’, Press Release, April 6, 2018. [21] This discussion is of course much broader, and it starts from the question of whether a data-based service falls within the material scope of, for instance, Directive 2005/29/EC. According to Art. 2(c) corroborated with Art. 3(1) of this Directive, it does. See also Case C‑357/16, UAB ‘Gelvora’ v Valstybinė vartotojų teisių apsaugos tarnyba, ECLI:EU:C:2017:573, para. 32. |

This is a crosspost from the Stanford Transatlantic Technology Law Forum Newsletter, Issue 2/2018 More blogs on Law Blogs Maastricht - image by Flickr: Spencer E Holtaway

-

The technique of academic research: on research lines and second brains

An important part of becoming a fully-fledged academic is the development and curation of a research line. A research line is the main research topic and the thread throughout (large parts of) a career. It could be law and technology in private law, globalisation in public law, human rights in...

-

Don’t sweat the small stuff? The new proposal for the EU directive on corporate sustainability due diligence

On 23 February 2022, the European Commission released the much anticipated proposal for the Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence. The aim of this Directive is to reduce human rights violations and environmental harms across the global value chain by making large companies carry out...

-

M-EPLI’s commitment to the “private side” of a sustainable world continues…

Achieving a sustainable way of life requires massive societal changes and (private international) law should enable, rather than hamper, the realization of such essential goals.