The proliferation of game clone in China versus copyright law

“Game clone” means two kinds of act: one is the act of game piracy, where the second game is a reproduction or abridgement of earlier games. Another act is that of creating games where second game contains similar elements as compared to earlier games.

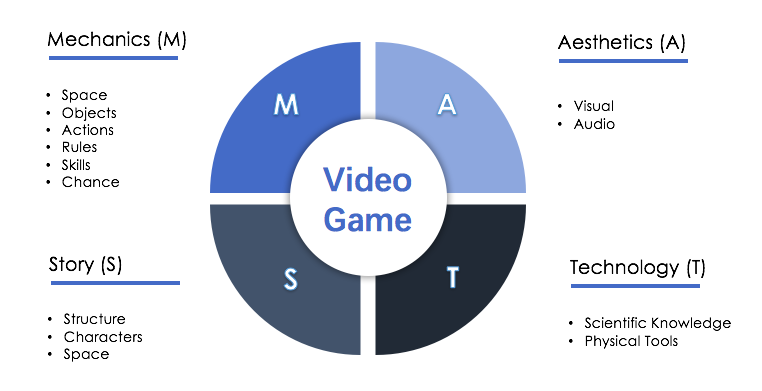

“Similar elements” here refer to design elements of a videogame - “mechanics” (including game rules and other abstract relationship among the components in a videogame), “story”, “aesthetics” (the presentation of a videogame), and “technology” (the programs and other technical ways in creating a videogame).

Elements in a video game

Copyright protection for videogames

In nowadays China, the booming of videogame industry results in a proliferation of game clone. In order to avoid the negative effects from that development, more game developers enforce the copyright their games enjoy and hence put forward more lawsuits. Since a videogame is not a typical subject matter in copyright law, a court presented with an infringement claim needs to decide on a series of issues: (1) whether a videogame is protectable under copyright law; (2) if so, what kind(s) of work(s) are protected; (3) what rights may be infringed by the act of game cloning; and (4) how to decide upon such an infringement. Based on that background, Xiao Wang’s PhD research aims at identifying gaps in Chinese copyright law when addressing the above issues; and if so, how to fill those gaps.

Lack of guidance at international level

Since China is a member of a series of international copyright treaties in the world wide, international treaties, such as the Berne Convention, the World Copyright Treaty, and TRIPs Agreement, provide limited guidance in solving above legal issues brought by the proliferation of game clone in China. Outstanding issues - including the originality requirement, the categories of works a videogame falls in, and the decision-making on infringement - should be further decided on the national level. Therefore, this research uses US and Japan as reference countries, the approaches of which are compared to and considered for China. These countries have been chosen as objects for comparison for the following reasons. First, the US has a different legal tradition (copyright tradition) to China, and Japan has the same tradition (author’s right tradition) as China. Second, the US and Japan have world-wide influential videogame industries and have a lot of videogame cases.

Chinese perspective

That national comparison tells us that for China, further analysis and suggestions are needed in the following three aspects: (1) Since US, Japan and China all protect videogames separately as videogame computer program and videogame screen display, is protecting the videogame as a whole better than as separate subject matters? When protecting the screen display, the US and Japan consider it as a whole under the label of “audiovisual/cinematographic work”, while China focuses more on the static images under the label of “works of fine art”. Which approach should China adopt? (2) US courts carry out a more detailed analysis on the scope of protection of both videogame computer program and screen display as compared to Japan and China. What can Chinese courts learn from that experience? (3) When comparing the disputed videogame screen displays, US, Japanese and Chinese courts all claim that they take the perspective of ordinary observer. This approach is strongly criticized because there are many technical elements in the screen display that are beyond the recognition by an ordinary observer. What perspective should Chinese courts take in this perspective? Xiao Wang’s research seeks to answer these questions.

|

Written by Xiao Wang, PhD candidate at Faculty of Law, Maastricht University |

-

Protection of reputable marks beyond confusion: does “due cause” help to strike a balance between trade mark proprietors and content creators?

Content creators, exercising their freedom of expression, may use trade marks in their content in a way that might damage the interests of trade mark proprietors (e.g. use of Nike shoes in a porn movie). How does EU trade mark law address these different interests?

-

Computer-Implemented Inventions: has the term “invention” in the EPC lost its meaning?

The European Patent Convention defines subject-matter that is not eligible for patent protection, such as methods for doing business. However, when implemented by a computer, non-eligible subject matter becomes eligible for patent protection. Is this desirable?

-

The ambigous nature of the amended European trademark functionality doctrine

EU trade mark law excludes certain signs from becoming registered trade marks. In particular, shapes cannot be registered if they are necessary for achieving a technical result. In 2015, the amended Regulation broadened this exclusion to ‘another characteristics'. But what is now covered exactly?