Who wants to use my (m)ap(p)?

Brigitte Le Normand, Associate Professor in History, researches socialist Yugoslavia in a global context. She has had three broad research agendas, all focusing on modernisation processes in the former socialist country. Her last big research project was about Rijeka, the main port in Yugoslavia. In unravelling its complex history, Brigitte embarked on a journey to engage communities in creating digital narratives.

Rijeka’s multifaceted history

Rijeka, a city located in present-day Croatia has a tumultuous past. It was part of the Habsburg Empire until the First World War. When the empire was dissolved after the First World War, the majority of inhabitants spoke Italian, but a significant number spoke Croatian as well – and many people spoke both languages. Initially, Rijeka became a free city, but it was later absorbed by Italy, and at the end of the Second World War, Yugoslavia took control of the city. As a result, Italians and Croatians hold contrasting memories of Rijeka’s past, shaped by historical events and cultural shifts.

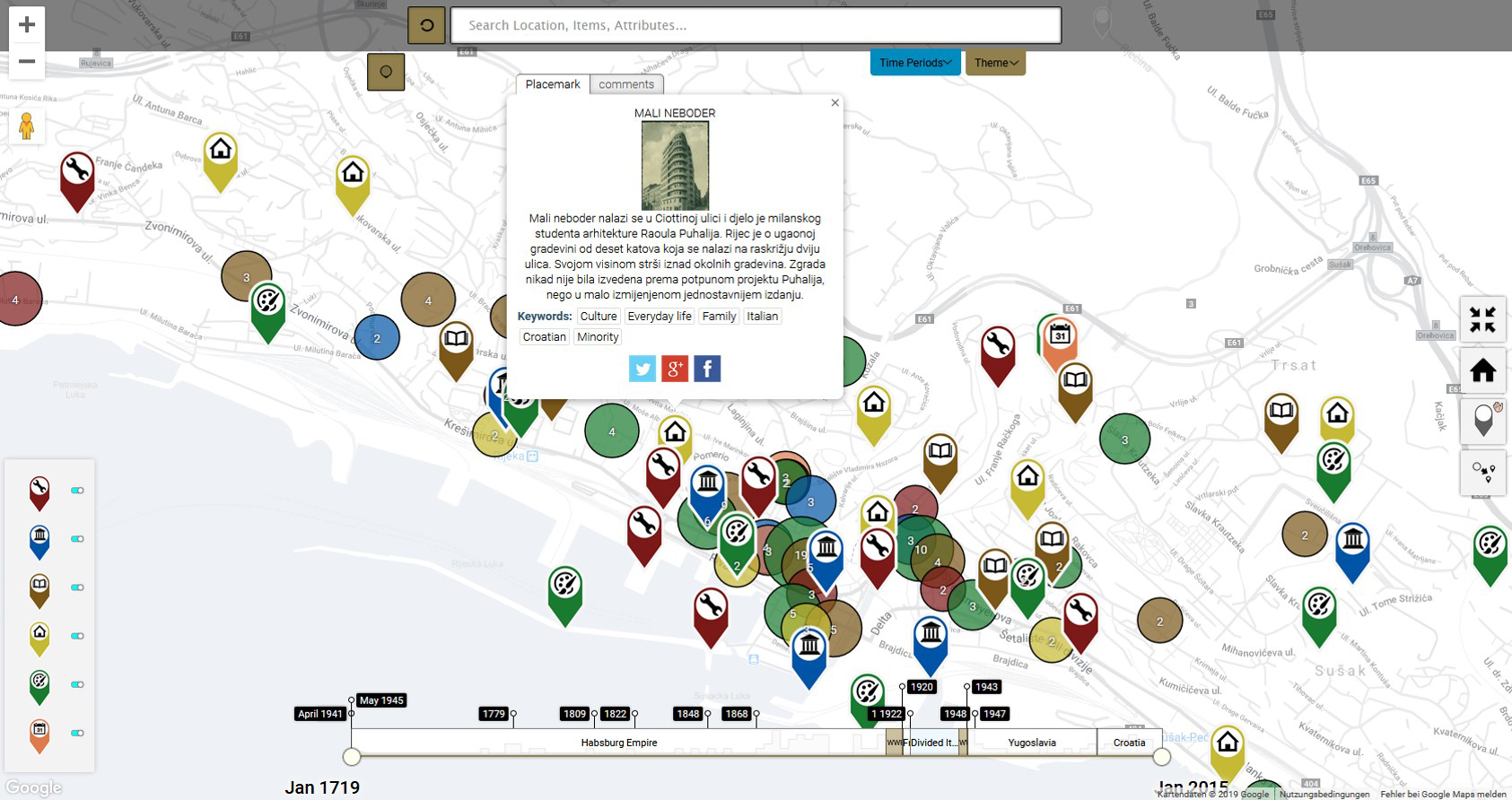

Mapping Rijeka’s stories

Driven by a desire to bridge these narratives and foster a shared understanding of Rijeka’s history, Brigitte created an interactive online map. “Since I knew that there were so many strong and contrasting memories about Rijeka’s history, I thought inhabitants would be interested in contributing to the crowd-sourced map. Ultimately, only a few did so.” Brigitte draws several lessons from this. “I think the problem was threefold. First, the platform that hosted the interactive map wasn’t as user-friendly as I thought it was. Second, potential users didn’t know what was in it for them when they would contribute to the map. They already had their own network and used other platforms to reach their audience. Third, my assumption that Croatians and Italians would want to interact with each other was wrong: they did not want to speak to those on the other language side.”

Even though the map was a bust, it was ultimately not a waste of resources. “Although the map did not fit its original purpose, it was used as a teaching tool, and a way to research and upload material to learn how to communicate historical research in an enticing way. Moreover, there are a handful of people that have found the map and started uploading their stories. It would be interesting to find out who these people are and what brought them to use the map.”

Walking the history of Rijeka with an app

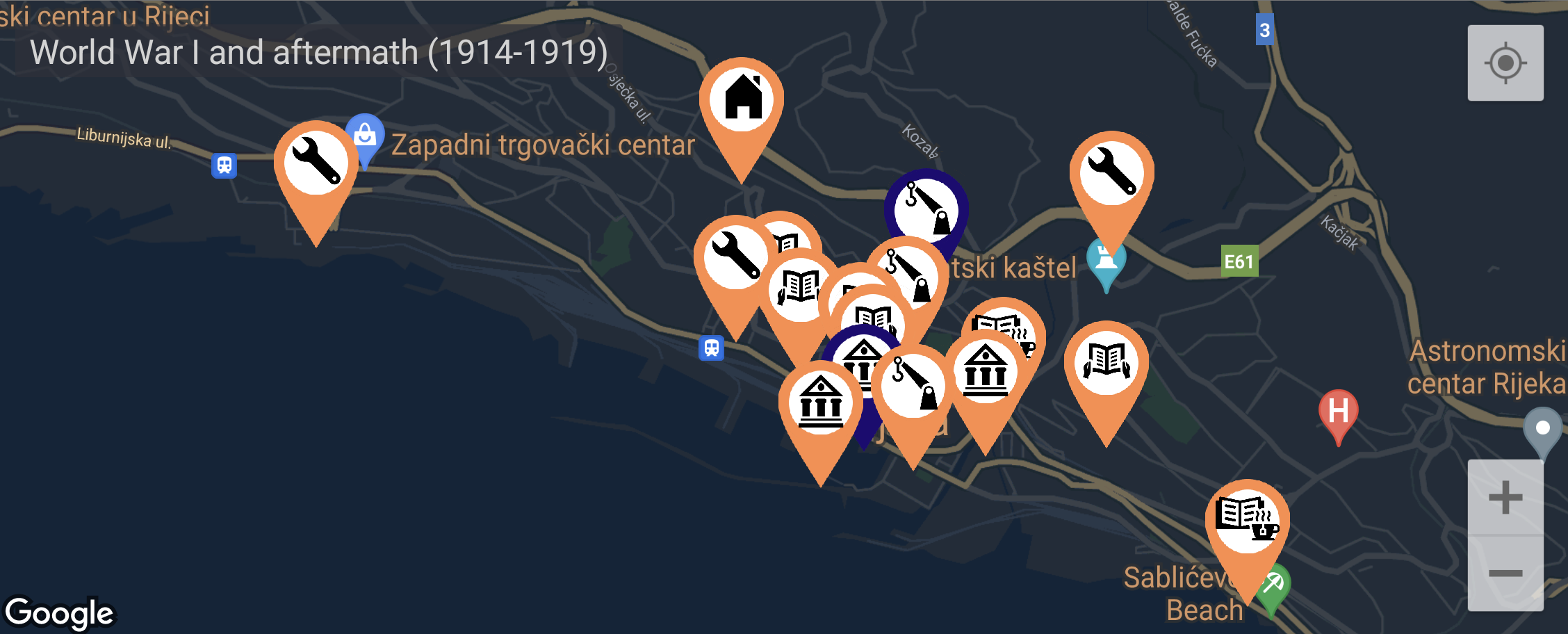

The failure of the map made Brigitte rethink her target audience. Who did she want to reach with the stories of Rijeka? “The people on the street. A map on the internet isn’t very usable then, so the idea of the creation of a mobile phone app about the history of the city emerged. I also learned from my previous mapping experience and decided not to rely on the Rijeka community to map this history. Instead, I invited historians to share their research. They would be able to craft high-quality content, transcending national narratives and offering a comprehensive view of the city's past, showcasing the many different stories that can be told about it.”

Yet, while the resulting app is impressive, it has struggled to reach its intended audience. Part of the problem may have been the effort to appeal to a universal user, including locals, tourists, and individuals of all ages. However, locals perceived themselves as already familiar with the city's history, while older demographics were less inclined towards mobile apps. High school students and tourists emerged as the primary users, albeit with varying degrees of engagement. “Students use it mainly because their teachers tell them to do so. At least since we now know which groups use the app, we can tailor the content much better.”

Recognizing the challenges faced by local educators during the COVID-19 pandemic, Brigitte redirected her focus towards tourists. “The tourist board in Croatia wanted to attract more tourists as they were hit hard by travel restrictions from other countries, but they seemed to be going through a constant reorganisation which made it difficult to create momentum. Here, I learned another valuable lesson: I should have had a local partner who could have helped me with effective promotion and outreach.” She continues to work on finding ways to promote the app with tourist audiences.

Lessons learned

Reflecting on these challenges, Brigitte returns to the drawing board with renewed determination. While the app may not have met initial expectations, users from outside of Rijeka have been enthusiastic, and researchers have expressed interest in the app as well. “My idea right now is to create a platform for other researchers who want to make such an app.” Brigitte emphasizes the importance of involving stakeholders from the outset, integrating their insights into the design process. On top of that, the entire process has allowed her to reflect on the potential and the challenge of research impact. “As academics, we publish a lot and we try out new approaches to generate outreach. But the real question is: has your work resonated in society; has anyone read it?”

Despite her own critical self-reflection, Brigitte cautions against fixating on failure, viewing setbacks as integral to academic research. “We celebrate our successes but we don’t know what to do with failure. A more open dialogue about failure would be beneficial, as it helps us to reflect and ultimately contributes to success.” In her quest to elucidate the multifaceted history of Rijeka, Brigitte remains committed to engaging communities, transcending boundaries, and embracing failure.

By: Eva Durlinger

Portrait picture by: Eric Bleize

Also read

-

The University Fund Limburg's new Annual Fund Campaign is live!

Every year during the holiday season, the UM community comes together to uphold a special tradition: supporting projects that contribute to a healthier, fairer and more sustainable society. Will you join us?

-

SBE researchers involved in NWO research on the role of the pension sector in the sustainability transition

SBE professors Lisa Brüggen and Rob Bauer are part of a national, NWO-funded initiative exploring how Dutch pension funds can accelerate the transition to a sustainable society. The €750,000 project aims to align pension investments with participants’ sustainability preferences and practical legal...

-

Fresh air

Newly appointed professor Judith Sluimer (CARIM) talks about oxygen in heart functioning and the 'fresh air' the academic world needs.