Performance-enhancing pill

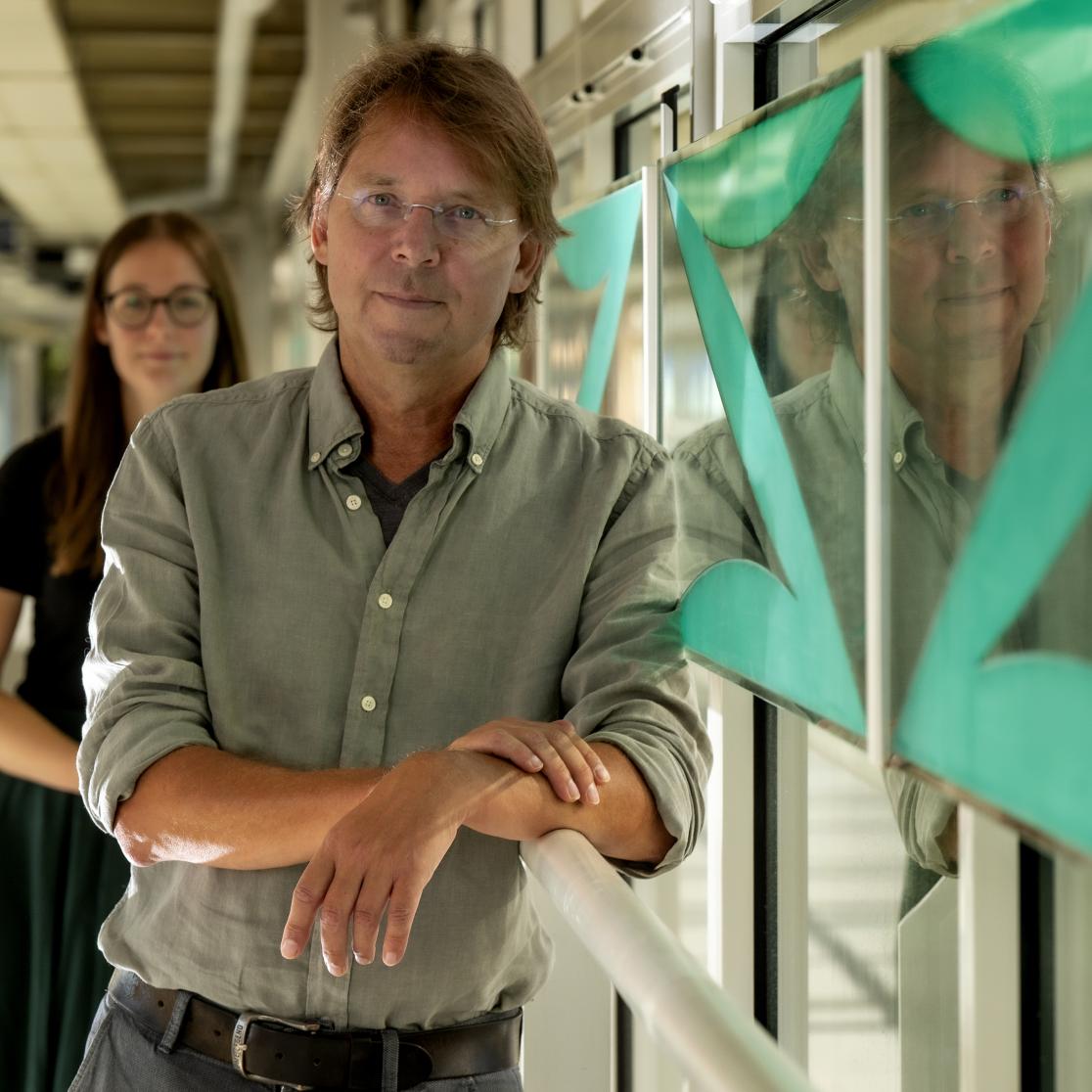

Increasing numbers of young people reportedly make regular use of low doses of LSD or other illegal substances to improve their cognition. Disquiet among parents and educational institutions is growing. Nadia Hutten investigated this phenomenon during her PhD, supervised by Professor Jan Ramaekers. How dangerous is this type of ‘microdosing’? And does it actually enhance students’ performance?

No, Hutten has never used drugs to improve her own mood or cognition. Nor does she personally know anyone who does. Yet this type of drug use lies at the heart of the research for which she recently obtained her PhD. “I kind of fell into this field, building on interesting previous projects at the Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience,” she says.

Cocaine and creativity

Hutten investigated whether students actually function better after using drugs. Word has it that cocaine makes you more creative, or that a microdose of LSD helps you study faster. But is it true? “Not per se,” says Hutten. She asked healthy volunteers between the ages of 18 and 30 to perform various tasks after taking cocaine, cannabidiol, LSD or a placebo. “Only a minority of participants reported feeling or performing significantly better. That being said, we did measure a subtle improvement in some people’s responsiveness while performing the tasks.”

“Nadia’s research demonstrates once again that drugs affect everybody differently,” says her supervisor Jan Ramaekers. “We should point out, however, that this study wasn’t double-blind. Some participants were aware they’d been given either a placebo or drugs; the resulting expectation can influence what they report.”

Just a coffee then

Research like Hutten’s can shed light on the actual impact of low-dose drugs, something we still know little about. How dangerous is regular use? And does that danger extend to the unlawful use of medicines, such as Ritalin? “Although long-term data is lacking, we don’t expect microdosing psychedelics like LSD to cause long-term harm,” Ramaekers says. “We do know that abuse of other substances, such as amphetamines, can lead to health damage. We see less danger in the use of LSD: it’s not a toxic substance and is known to be relatively safe. At the same time, we don’t expect people to perform better after a low dose of LSD than after a cup of coffee. The effects are minimal.”

New claims

Society has long been preoccupied with the downsides of drugs. In recent years, however, attention has turned to potential upsides and clinical applications: the use of cannabis as a painkiller, for example, or mushrooms as antidepressants. “These developments give rise to a more positive view of drugs, which in turn results in new uses, such as microdosing psychedelics when studying,” Ramaekers says. “It’s important to respond to these new claims and practices from a scientific perspective. We have to acknowledge their presence, not immediately dismiss them as nonsense, and above all examine them with a critical eye.”

Distorted picture

With rising public interest in the topic, the media has begun to report more frequently on drugs to improve cognition. These messages sometimes present a distorted picture. “One recent headline reported that 20% to 30% of students use cognition-enhancing drugs, but that’s not systematic use,” Hutten says. “It’s mainly students who’ve tried it to cope with study stress or for the sake of experimentation. We don’t see that as a major problem in society. But it can be a signal for university administrators to consider issues such as whether the study load is too intense.”

“We need to communicate transparently about LSD microdosing,” Ramaekers adds. “All the media attention for the potential applications of microdosing psychedelics creates false expectations. The first controlled studies, like Nadia’s, show that the effects are negligible. But few publications report on this and thereby temper users’ expectations. The media and research institutes have an important role to play here. People need a realistic picture of the effects of a low dose of drugs, so they can weigh up the pros and cons for themselves.”

Not mapped out

How does Hutten look back on her PhD research? “It was an instructive process, thanks in part to Jan and my two other supervisors. Jan in particular taught me to view things from a broader perspective.” Ramaekers is satisfied too. “Nadia has developed both as a scientist and as a person.”

Hutten’s work offers ample opportunities for follow-up research. “We could zoom in on the clinical applications of microdosing drugs, or on the impact of low doses on different types of productivity or creativity. I’m also working on a study with older participants, instead of students,” she says. In other words, there is no shortage of work to be done. And after that, Hutten hopes to stay in the world of research. “Which is definitely not to say my career is already mapped out.”

Text by: Milou Schreuders

Photography by: Harry Heuts

Jan Ramaekers is professor of psychopharmacology at Maastricht University. His research group focuses primarily on the relationship between drug use and behaviour. Ramaekers studied psychology in Groningen, specialising in experimental psychology. In 1989 he relocated to UM, where he was closely involved in the establishment of the Institute of Human Psychology and the Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience.

Also read

-

A new wave of talent emerges from the School of Business and Economics

On Sunday, November 30, 2025, the Maastricht University School of Business and Economics (SBE) proudly celebrated the achievements of over 1,461 graduates from both bachelor’s and master’s programs. The festive ceremony took place at the MECC Maastricht and marked a significant milestone for the SBE

-

Roy Broersma (CEI): Guiding Aestuarium from idea to venture

Roy Broersma, director of the Center for Entrepreneurship & Innovation (CEI) at SBE, has been closely involved in guiding Aestuarium from an early student startup to a growing venture. From spotting their potential during the Brightlands Startup Challenge supporting them through CEI.

-

From Study to Startup: The story behind Famories

When Lennie and Neele graduated, while many of their classmates were busy fine-tuning CVs and stepping into roles at top companies, they took a detour by recording podcasts with their grandmas. What began as a charming way to cherish family memories has blossomed into Famories, a vibrant startup with a...