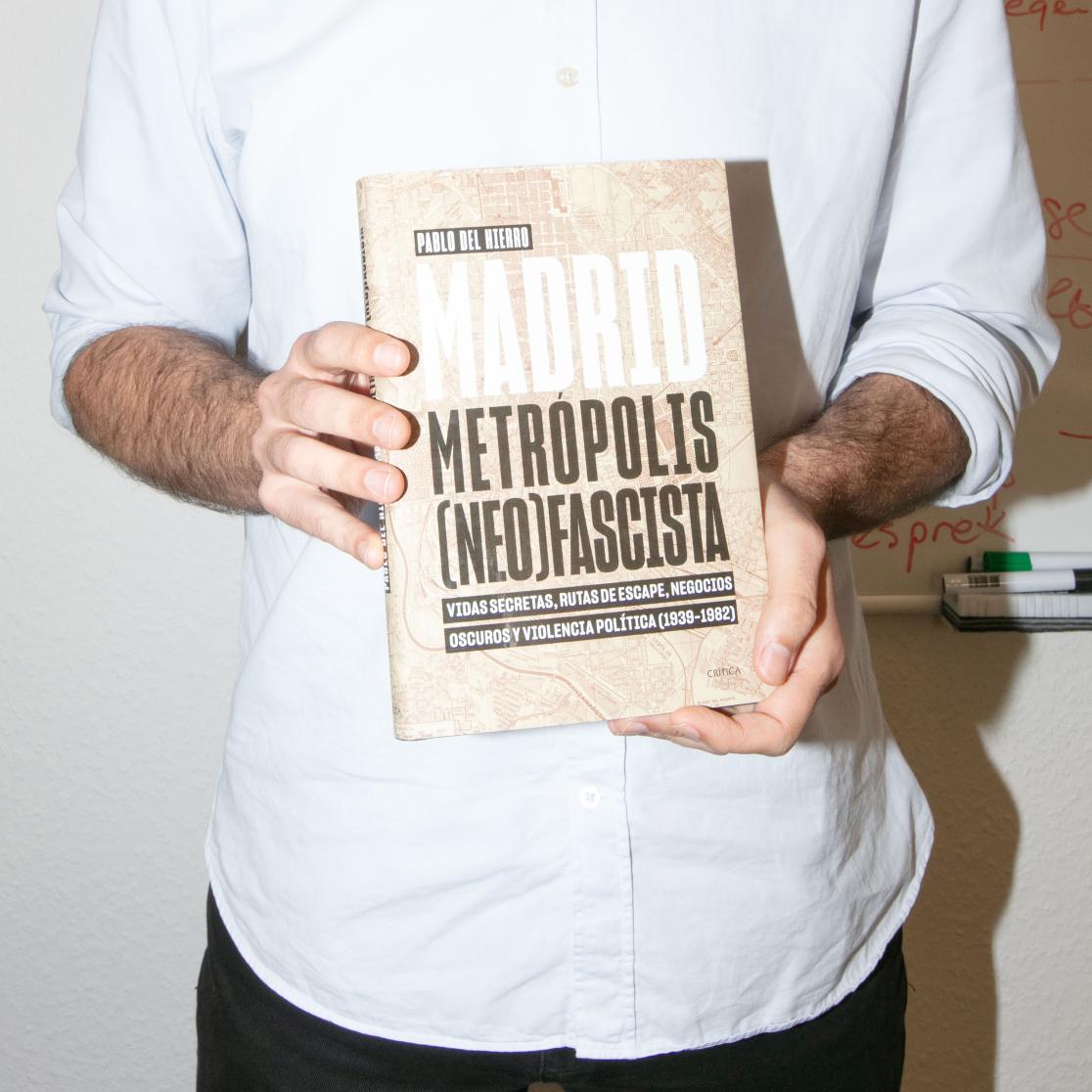

(Neo)fascist metropolis

Pablo del Hierro’s work on transnational fascism in his native Madrid has led to a book, a documentary, the FASoS Valorisation Prize and a political campaign to remove a fascist monument.

Pablo del Hierro was 13 when he passed a statue of General Franco astride a horse in Madrid. His native city used to boast many fascist monuments, and he had never given it much thought. This time, however, a large neofascist rally had gathered by the statue. “My friend was wearing this red Che Guevara shirt. A group of skinheads saw us and chased us. We really had to run to get to safety,” Del Hierro recalls. “That’s when I was first confronted with how real and violent neofascism really is.”

It wouldn’t be the last time. A lifelong Atlético de Madrid supporter, Del Hierro was in the stadium when a far-right faction member killed a fan of Real Sociedad, a club based in the Basque region associated with fierce opposition to Franco. Indeed, much of Del Hierro’s research into neofascism is linked to the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s ascension to power in 1939.

“After 1945, Madrid was one of the few remaining refuges for fascists. The Franco regime provided safety. Intellectuals and political activists arrived from all over Europe to share ideas and best practices, which led to even more immigration.” While the importance of cities like Lisbon and Buenos Aires waned due to cultural and political changes, Madrid remained a hub for fascism well into the 1980s.

Transnational ultranationalists

Ultranationalism would seem a strange bedfellow for transnational collaboration. “The remaining fascists had to make a virtue out of necessity. Even during the interregnum years, far-right groups across Europe tried to collaborate, but couldn’t bridge their ideological differences. WWII left them decimated and scattered; they had to stick together regardless of their prior disagreements.” Del Hierro traces how the Europeanist tendencies that developed in Madrid became mainstream among younger neofascists.

To Del Hierro, recent election results are best understood in a historical context. “Movements like Identity and Democracy [a far-right political group in the European Parliament] are nothing new. As early as 1979, far-right groups tried to forge an alliance for the first elections to the European Parliament. These initial projects failed for different reasons—but through repeated trial and error, they learned.” The idea of leaving the EU had been gaining traction among such parties across Europe, but the consequences of Brexit exposed that policy as a pipedream. “They adapted. None of these parties suggest leaving the EU anymore. The rhetoric has shifted towards reforming in a similar vein to the 1950s slogan, ‘Yes to Europe, not this Europe.’”

Understand, not underestimate

If all this makes the far right look like formidable political operators, that is Del Hierro’s intention. “If we want to fight fascism, we need to stop minimising it. We need to understand it better. We have to dispel the myth that extremists are inept, incompetent ignoramuses. They are truly dangerous, well-organised and well-resourced. They keep learning and seem to have found a formula for success.”

To understand the evolution of the far right, he says, it is crucial to study the underlying network of intellectuals and think tanks across Europe, but also to dispel the myths surrounding their voter base. “They are products of their conditions. Secularism and globalisation are seen as having eroded people’s sense of identity. At the same time, the 2008 economic crisis has left people feeling that living standards have declined and will continue to do so.” The far right’s success among younger voters can be attributed to its appeal to this pessimistic outlook, along with its social media savvy.

“They’ve found a way to address the zeitgeist in a way that traditional parties haven’t,” Del Hierro says. A vague sense of decline and decadence, a once-glorious Europe of nations betrayed by the global elite. “And then you offer easy solutions to address those problems. Get rid of foreigners, so it’s easier to find jobs, housing and so on.”

He stresses that simply dismissing people’s concerns—or indeed the shrewd political operators who exploit them—is counterproductive. “When I started this line of research around 12 years ago, my colleagues said it was just a fringe phenomenon and not worthy of attention. But I became convinced that this was a serious problem that would only get worse.”

Difficult societal conversations

Del Hierro published his findings in an academic journal that attracted the attention of publishers. The subsequent book reached journalists, producers and political activists. “Much of it is about the urban geography of Madrid; it’s very visual. So they decided to make a documentary, which will likely be broadcast next year for the 50th anniversary of the end of the Franco dictatorship. After that, we’ll take a longer version to festivals to reach more people.”

Del Hierro is also working with political activists. “The United Left movement has sent several petitions based on my research to remove a fascist monument in Majadahonda [a municipality near Madrid]. There are far-right gatherings there every year, but the right-leaning local government is still undecided.” The controversial Historical Memory Law calls for the removal of all monuments that glorify Franco’s reign, which lasted until 1975. “Rather than destroying monuments, I think we should contextualise them. It’s very complicated, but it’s good that this conversation is finally happening in Spain.” Del Hierro’s journey has led him back to the kind of monument where it all began—and there is still plenty of work to do.

Text: Florian Raith

Photography: Paul van der Veer

Also read

-

Flour, family, and forward thinking: the evolution of Hinkel Bäckerei

In the heart of Düsseldorf, the comforting aroma of freshly baked bread has drifted through the streets for more than 130 years. Since its founding in 1891, Hinkel Bäckerei has evolved from a small neighborhood bakery into a cherished local institution.

-

Contribute to a Voice for Children in Conflict Areas

Dr Marieke Hopman and Guleid Jama are launching a new research project on the role of children in peacebuilding in conflict areas.

-

Administrative integration through agency governance The role of Frontex, the EUAA and Europol

PhD thesis by Aida Halilovic