Feeling lonely in PBL: a personal reflection

In this article, Carolina Cicati, a teacher at the Law Faculty of Maastricht University, explores how crucial trust is for effective Problem-Based Learning (PBL), even over brief periods. Drawing on her own experiences as both a student and a tutor, she discusses the challenges of building a collaborative learning environment when groups change frequently. The article encourages both students and educators to actively consider ways to create a more trusting and inclusive learning experience for everyone involved.

Feeling lonely in PBL

During my bachelor's programme at Maastricht University, it was customary for tutors and tutorial groups to switch every eight weeks. At first, I was delighted to meet new people from diverse backgrounds. However, this practice had an unintended consequence. Suddenly, I found myself feeling isolated on my academic journey. The intensive tutorial meetings, lasting seven weeks each, followed by the exam week, made it challenging to develop trustworthy relationships with my tutor and classmates.

I quickly learned that people come and go, but my academic progress must remain consistent. I moved on, but I felt something was missing in my study experience, that had to do with working with my fellow students, as fellow learners.

From student to student-tutor

My perspective changed in my third year of studies when I was selected to become a student-tutor. I joined a small, tight-knit group of students who were all embarking on a similar journey. Our 18-hour training served as the foundation for our future collaboration. Our seasoned, experienced student-tutor peers became our mentors and friends, welcoming us into their existing community. We all gathered in the student-assistant room, which became our refuge. We had regular meetings with our peers and our coordinator. Our coordinator played a crucial role in our dynamic, always available to offer guidance and support when needed.

Looking back, I now realise that, next to some similarities, these two experiences have a few key differences. Some of the aspects that stood out in my student-tutor time were the consistent composition of the group over a longer period, a smooth introduction of new members, the role of our coordinator as a supportive figure, and our awareness of the team dynamic. These factors created a safe space for us where we could trust each other and our coordinator.

Dysfunctions in teams

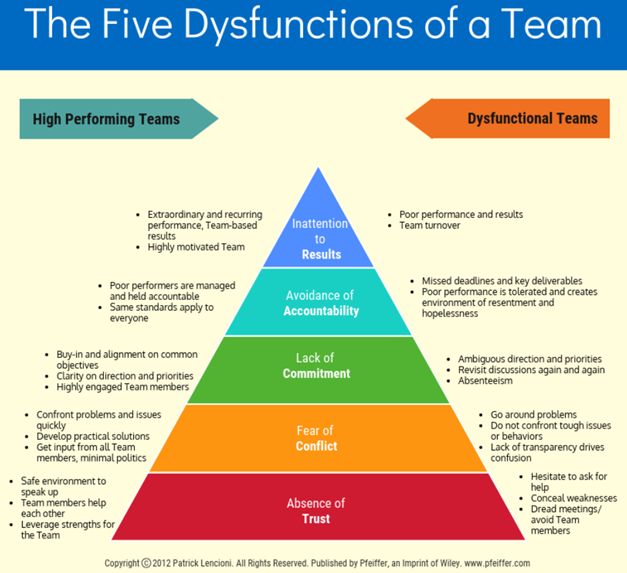

These experiences made me think about the Lencioni pyramid. Patrick Lencioni, an expert in organisational management and leadership, believes that a well-functioning team should be able to engage in healthy issue-oriented conflict and hold each other accountable for their behaviour. Lencioni identifies five common dysfunctions that a team must overcome to achieve desired results. These dysfunctions include the absence of trust, fear of conflict, lack of commitment, avoidance of accountability, and inattention to results.

The first step to overcoming these dysfunctions is establishing trust among team members so they can be vulnerable to each other (vulnerability-based trust). This is particularly relevant in teams where you cannot predict how someone would behave (predictive trust). This idea is also discussed by Harvard Professor Amy Edmondson, who states that "when people working in a group don't trust each other, and when psychological safety is low, they tend to focus more on achieving their own goals rather than cooperative goals’’.

The Five Dysfunctions of a team, Patrick Lencioni

Lessons from organisational management

Although both authors focus on how teams function in organisational environments, their findings are also relevant in educational settings. After all, when students participate in a problem-based learning (PBL) tutorial group, they are, in fact, supposed to function as a team of learners. The goal of the tutorial group is to generate knowledge individually and as a team, meet learning objectives, and solve an ill-structured problem. That seems to be the essence of ‘collaborative learning’: rather than just absorbing and transferring knowledge, students work together, feel comfortable asking for help or admitting their weaknesses, and overcome emerging cognitive conflicts.

Varying experiences in PBL tutorial groups

Clearly, the experience of participating in a tutorial group can vary. Some students see the frequent changes in tutorial groups as positive, especially if they don't feel like they fit well in their current group. Meeting new classmates and building friendships can be a benefit of switching groups. Additionally, having the opportunity to interact with different tutors throughout the programme can be advantageous, as each tutor has a unique style and can offer different perspectives on the subject matter.

The student's personality, life stage, and interest in a subject can affect how easily they adapt to new groups and teachers and how often they prefer to switch groups. For instance, an introverted student may prefer a stable group for an extended period, while an extroverted student may be keen to interact with a large variety of people.

Occasionally, I meet students who find it hard to show vulnerability and struggle to trust their teammates. They are uncomfortable with acknowledging uncertainty, saying things like "I don't have the answer; please help," "I want to hear others' perspectives," "I could be wrong," or "What ideas do you have?". Unfortunately, the limited time available in tutorials and the need to maintain a focus on the subject matter often prevent tutors from adequately addressing the needs of these students.

Interestingly, in my experience, when the distrustful students are absent in a tutorial session, the group dynamic might improve temporarily. However, upon their return, if the students are simply perceived as “the problem”, and the tutor and peers neglect or fail to integrate them back into the group, it could further damage the dynamics.

Building trust in short-term learning environments

It can be quite a challenge to find an approach that accommodates all students, given the advantages and challenges of any system or strategy one may implement. Building a trust-based environment in a short time is an even bigger challenge. However, the need for trust and psychological safety that Lencioni and Edmondson talk about is a condition for collaborative learning for all students – extroverts and introverts. So we may want to think about this a bit more.

With this article, I don’t intend to propose definitive solutions to the identified problem that affects the composition or frequency of tutorial groups in an educational programme. Currently, many academic programmes at UM apply short-term learning in PBL tutorial groups. Moreover, students may encounter similar environments in their professional lives, such as being part of short-term projects.

I do hope, however, that this reflection invites teachers and students to recognise the issue of establishing trust in short-term learning environments and consider potential actions that can be taken at the individual level to build more trust. How can we achieve this? Are we doing enough?

During the first tutorial, both tutors and course coordinators run introduction rounds, which is an excellent way for everyone to get to know each other. Group projects and explicitly inviting students to speak with each other during breaks are great means to build trust. Other ways to accommodate the group include reflecting and providing feedback on the group dynamic and making new arrangements.

Ultimately, flexibility and openness to personalise the dynamic in each group depend largely on the willingness of both students and tutors to find common ground that works well.

Sources:

- Patrick Lencioni, 'Five Dysfunctions of a Team', 2002

- Patrick Lencioni, 'The Ideal Team Player: How to Recognise and Cultivate The Three Essential Virtues', 2016

- Amy Edmondson, 'Teaming: How Organisations Learn, Innovate, and Compete in the Knowledge Economy', 2012

By Carolina Cicati, Teacher, Department of Private Law, Faculty of Law, Maastricht University.

This article is a publication of edUMinded, the Maastricht University online magazine on Teaching & Learning.

Interested in more Teaching & Learning insights?

Also read

-

Teacher Information Points at UM

UM faculties now host Teacher Information Points (TIPs) that offer local, “just-in-time” and on-demand support for teaching staff. The aim is simple: to provide help that is closely connected to day-to-day teaching practice.

-

As a teacher, how confident are you in your digital skills? Discover your capabilities in just 25 minutes

Maastricht University invites all teaching staff to take part in the Jisc Discovery Tool pilot to explore your digital strengths.

-

UWC Maastricht students get a taste of education innovation at EDLAB

On 21 October 2025, EDLAB hosted students from United World College Maastricht for the second year in a row, as part of their Youth Social Entrepreneurship programme.