How making videos changed my dismissive view of PBL

This is the story of...

...a teacher who was always somewhat sceptical of education theory but who changed his point of view after implementing PBL in his own way.

The Past

Yes, that teacher is me, just to be clear. And to tell this story, I need to go to The Past.

I used to be a researcher who liked teaching. I even liked teaching so much that after 15 years of research work, I voluntarily chose to drop research in 2015 to focus almost entirely on teaching. I wanted to teach, and in my case, teach math, as we can all agree that math is beautiful – and if you don't believe it, I'll convert you :-)

Diagrams vs direct contact with students

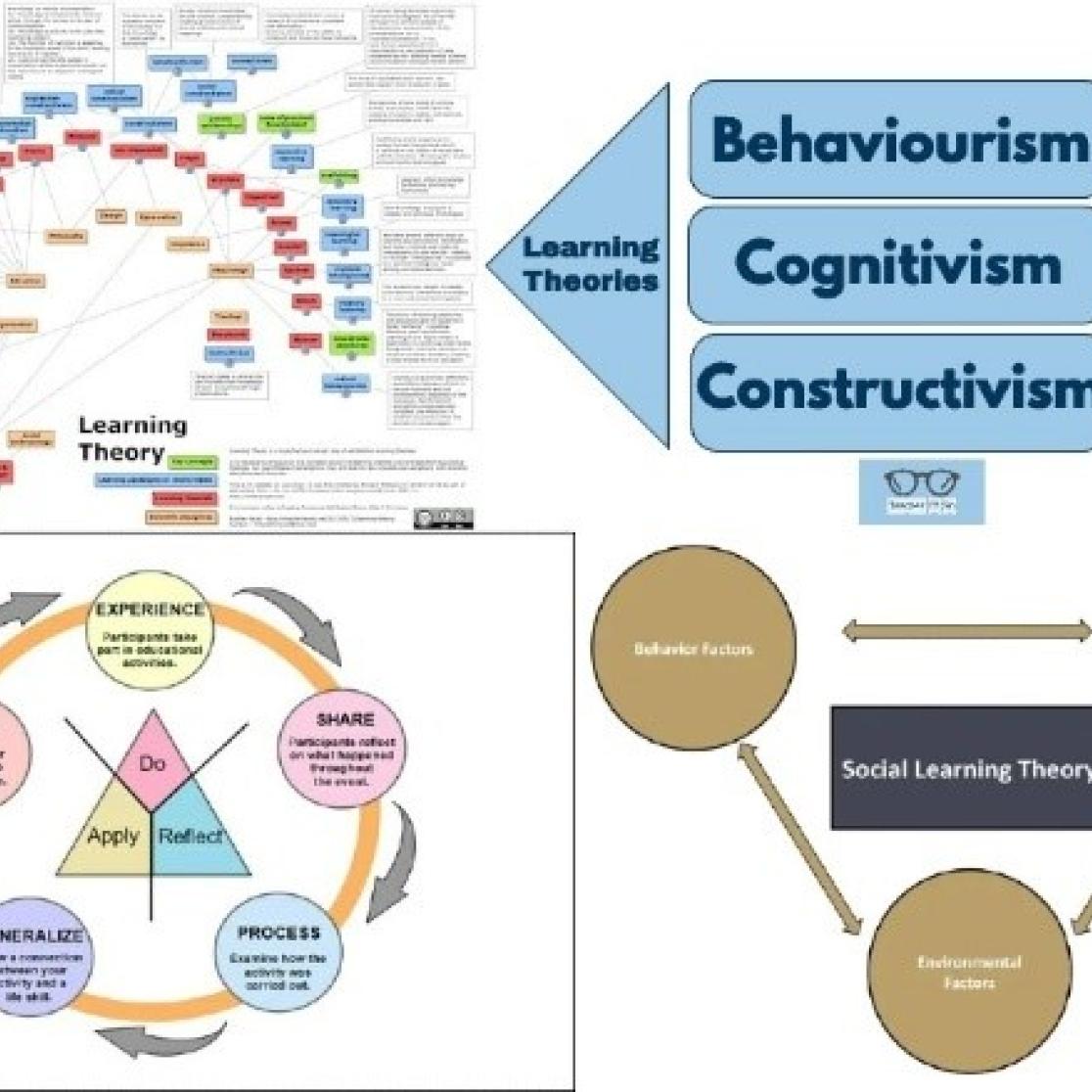

I was not interested in education theory, and my experience with "researchers in education" was mainly that they showed big diagrams of related education concepts, which were far away from my actual teaching. It felt similar to spending hours optimising how to play basketball using Excel sheets and calculators, only to discover that none of this matters when playing basketball.

I just wanted – and want, actually – to stand with my feet in the mud of actual contact with students and explain stuff to them. If these evil education researchers became in charge of your career path (for example, because you had to get a teaching qualification like UTQ), they imposed their theory on you, and you had to try to fit your practice into their theory. These theories all resembled each other and asked you to divide stuff into 3, 4, 5 or more boxes. (Recognise CCCS, anyone?)

Flip flop

In 2015, I taught at an education institution that trained future high school math teachers. Since we were asking our students to be Modern Teachers, we felt morally obligated to do some innovative teaching ourselves, too. My primary experience with innovative teaching happened in one class, which I flipped. Instead of lecturing, I made explanatory videos and turned the class meetings into meetings where students did exercises and asked questions. I diligently prepared my videos by making slides, practice runs, and a bit of video post-editing. Very, very time-consuming.

When the class finally took off, the students bombarded me with questions. Instead of working on exercises as anticipated, the class meetings became more like lectures, where I found myself explaining everything again because students were not used to working with videos. It was very nice that I wanted to flip, but the students did not. So, instead of flipping, the class flopped. For me, this experiment later turned out to be an important learning experience.

The Pandemic

Oh yes, we all remember that. Teachers suddenly had to become adept at online teaching, parents suddenly had to endure their kids joining class at home, and it took 10 months to get a new dishwasher delivered (much to my chagrin). Like many colleagues, I was teaching online and making videos again. I was the most experienced in this task in my department, due to the 2015 flipped classroom bout mentioned above, and I began to do it "quick and dirty" as there was absolutely no time to make slides. Also important: students got used to this method of receiving education, consisting of watching videos by themselves. They changed...

PBL and Algebra

Before coming to UM, I was aware of PBL education or variants, though not always under the same name. At first, I thought nothing special about PBL or its underlying CCCS principles. I just thought of it as another thing “to satisfy the education researchers”, of whom I wasn’t one. However, my perspective changed when I started teaching a linear algebra course for Business and Engineering, and that’s the story I’m telling here.

The Incentive

In this course, I was confronted with the following problem: The course came with only one weekly lecture, whereas all courses I taught at my department included two or three weekly lectures. From what I could see, I had to cover too much material every week for one lecture to be easily digestible.

I mean, it was definitely possible to cram all the material into one two-hour lecture – and from what I heard from the students, this often happened in other courses – but this option wouldn't make the learning experience very easy for the students.

I decided to complement the lectures with videos: the videos would contain the content material I would not cover in the lecture – and would not contain the material presented during the lectures. (This latter aspect was required as the department wanted students to attend the lectures and not receive all the content in the videos – which makes sense.) For each lecture, it was more or less natural (to me) what to teach in the lecture and what to put in the video.

Initially, I feared this would be a lot of work, but as it turned out, I could make "quick and dirty" videos of reasonable quality very efficiently. I estimate that it cost me about two to three times as much time as it took to play the video at average speed. Also, the videos turned out to be relatively short and compact. (See my second article to find out "How to quickly make videos that get 'The Job Done'.)

Next to that, I had to make do with the double tutorials per week.

It turned out to be surprisingly FUN!?!

Why is that? I was designing a course in a creative way; the scheme on how to let students learn suddenly was way more "open" than in "regular" classroom teaching as I was used to from other universities. It was a strange sensation to realise that I was recognising some of the theoretical concepts from PBL in a practical situation. Because I had more tutorials, taking a more PBL-like approach was almost automatic. I didn't go all the way with it, but as the weeks went on, it became more and more natural to apply PBL and the "collaborative" part of CCCS.

It also unearthed "new" difficulties: for example, I "only" gave 4 out of 26 (from 13 groups x 2) weekly tutorials myself, and it was necessary also to instruct the other tutors, who had diverse expertise and experience. This was quite a challenge, and I wouldn't say I 100% succeeded. Some of the tutors were professional tutors (and better than me) to whom I didn't even need to throw the ball for them to catch it, whereas, with others, I only noticed way too late in the course that the students were struggling. I sent out instructions through email weekly, thinking that that would be enough. I now know I will need to meet weekly if at least online, to discuss that week's tutorials.

As time passed, I saw that I was naturally and concretely doing stuff propagated in PBL and CCCS, but simply coming from me. It caught me off-guard, as I'm now quite enthusiastic about this, and I look forward to expanding this in future courses. It also made me think: all universities I have worked for so far claimed to be teaching-oriented, but as far as I see it, they're nowhere near UM.

I started realising that UM puts way more resources into teaching personnel – as PBL is teaching-intensive. For example, there are dedicated professional tutors here who are really, really good – shoutout to my bros Prag Mehta and Ioannis Diamantis! And I think it pays off! I really get enthusiastic about this as I see how much it benefits the students, and – again – it is so much fun.

"The videos get the job done"

I asked students a few times what they thought of this setup. Obviously, they were happy with having part of the material in videos, if only because they could watch them at their own pace, in their own time, and could rewatch things. They never mentioned “speeding up”, but I imagine that can be done too. They were sort of OK with the fact that not everything was in videos and that the lectures contained material that could not be found in videos.

A few students said they would rather have had an additional lecture than videos. The visual and auditory quality of the videos was OK for them. A few mentioned that videos could have been smoother or slicker – while recognising that “they do get the job done”. Overall, the response was very positive.

Interactive, Constructive and Collaborative learning

Let me not shy away from the theoretical aspect and spend a few words on the CCCS principles here. The PBL educational design for this course could be found in several of its elements. The autonomous watching of videos by students connects to the S of CCCS (Self-directed). I could make the tutorials more interactive, which better put the first and third C of CCCS (Constructive and Collaborative learning) on the map.

For instance, more examples and questions were discussed with the tutorial groups as a whole, and there was more room for students to work out exercises in front of their peers, making very instructive errors. Students who were not at the front of the class became quite engaged in understanding their peers, correcting them, or comparing their results to theirs.

Just one example of where I saw a clear difference in results. In some of my former courses, I sometimes caught students “swimming” (i.e. not operating on solid ground), meaning that they did not understand the most important concepts of the first few lectures – often, I only noticed this in the final exam, which (obviously) was way too late. Now, I saw it hands-on in early tutorials and sometimes could adjust it on the spot: I could at least make a student aware of what they didn’t understand and what they should focus on to make things more "solid’’ for them.

Breathing life into PBL

The key message for me from this experience, and hence this article, is that theoretical education concepts are not only theoretical, and in particular, that PBL and CCCS appear naturally when doing a specific type of teaching. They are not (one of the many) concepts being shoved down your throat because you need to obtain your teacher qualification, but they appear naturally.

Once you experience that, the concepts become alive, and the buzzwords PBL and CCCS are just some of the best ways to describe some of these concepts. I did not write this article emphasising what PBL did for the students, but what it did for the teacher.

All in all, the experience of making videos changed my view of PBL and CCCS from some theoretical concepts into something very practical and hands-on. If you have to write down these concepts in a general theoretical framework, the description doesn’t show how it really feels to work with them. And perhaps that’s what I want to say here: education theory doesn’t live for you unless you have truly felt it by putting it into practice in your own way.

By Stefan Maubach, Teacher, Department of Advanced Computing Sciences, Faculty of Science and Engineering

Interested in more Teaching & Learning insights?

Also read

-

Teacher Information Points at UM

UM faculties now host Teacher Information Points (TIPs) that offer local, “just-in-time” and on-demand support for teaching staff. The aim is simple: to provide help that is closely connected to day-to-day teaching practice.

-

More than another ‘to-do’: how the UTQ helped me rethink my teaching

At Maastricht University, the University Teaching Qualification (UTQ) is a professional development programme designed to strengthen teaching and learning. It supports teachers in developing core teaching competencies through a combination of workshops, peer learning, on-the-job experience, and...

-

How I rely on my university-taught writing skills, now that I use ChatGPT as my daily assistant at work: perspective of a recent graduate

How does a recent graduate transition from using AI tools with caution at university to embracing them at work? In this article, Helen Frielingsdorf shares her experience of adapting to AI, particularly ChatGPT, in her professional life. She reflects on how the writing skills she developed at...