Object- and Problem-Based Learning (OBL & PBL): A Fruitful Amalgamation for the Development of Legal Education

Patrons at the Arthur W. Diamond Law Library at Columbia University (USA) can encounter a duplicate of an automobile wheel that relates to the 1916 court case heard by Judge Benjamin Cardozo in MacPherson v. Buick Motor Co. The wheel is an object that hangs on a wall on the fourth floor of the library. Instructors could take the wheel to the classroom when dissecting that landmark case and when dealing with the core problem around the case: product liability. The use of the wheel helps to materialise the elements that are addressed in the court reporter, in the casebook, and in the daily-life situation that motivated the decision. Similar educational experiences can take place when students are welcomed at a rare book room and encounter for the first time a medieval copy of the Corpus Iuris Civilis. Some experiences are indeed indelible and help visualise what dozens of prescribed readings and explanations by an instructor cannot make easily evident and memorable.

The Object

Education has benefited from observing objects and using them as a teaching resource. Legal education is no exception, and in recent decades the use of objects has increased significantly at universities across the globe. That increase is accompanied by the activation of other sensorial educational experiences, such as those triggered by images (ia, film, photographs), sound (ia, music, voices, noises), smells (ia, odours, fragrances), and emotions (ia, discovery, happiness, solitude). Every experience adds to the educational process–if adequately presented–to convey knowledge and to facilitate the learning path. The use of objects has motivated the development of Object-Based Learning (OBL) techniques, and copious literature is being produced on those techniques, aiming to explain the strengths and challenges of that way of learning.

The Problem

Looking at a problem as a means to attain legal knowledge has gained ground at multiple universities, with Maastricht University offering a fertile laboratory for this active way of learning. Students are faced with problematised situations that need to be addressed in order to better understand how law operates in the texture of society. Copious literature has been developed on Problem-Based Learning (PBL) during the past decades and best practices are being shared amongst those who cultivate this active way of learning, triggering an up spiral of positive developments in the existing techniques. The traditional approach to PBL (ie, the seven steps) has been surpassed and innovation is out there, for example, aiming to experiences that enrol in CCCS educational principles (ie, Constructive, Contextual, Collaborative, Self-directed). Passive means of legal education are giving way to active experiences, and the attention to a problem is amongst the most recurrent approaches when implementing active pedagogical tools.

The Amalgamation

Intercultural barriers in a PBL environment can be bridged by the study of an object. There are universal messages embedded in objects and they go beyond words and terminologies. Further, objects can trigger prior relations to the problem that is being studied. Gathering around an object in a PBL environment can activate new ideas and perspectives. For example, during a brainstorming phase students can build experiences around an object, such as translating an object into a mind map or as a visualisation of a problem in a different way, be it more realistic or challenging previous visualisations. Interacting with an object during the brainstorming phase can further assist in the learning experience by enabling paths to reach consensus or by eliminating common misunderstandings. Objects can ultimately serve to triangulate data and to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a problematised situation.

The Resources

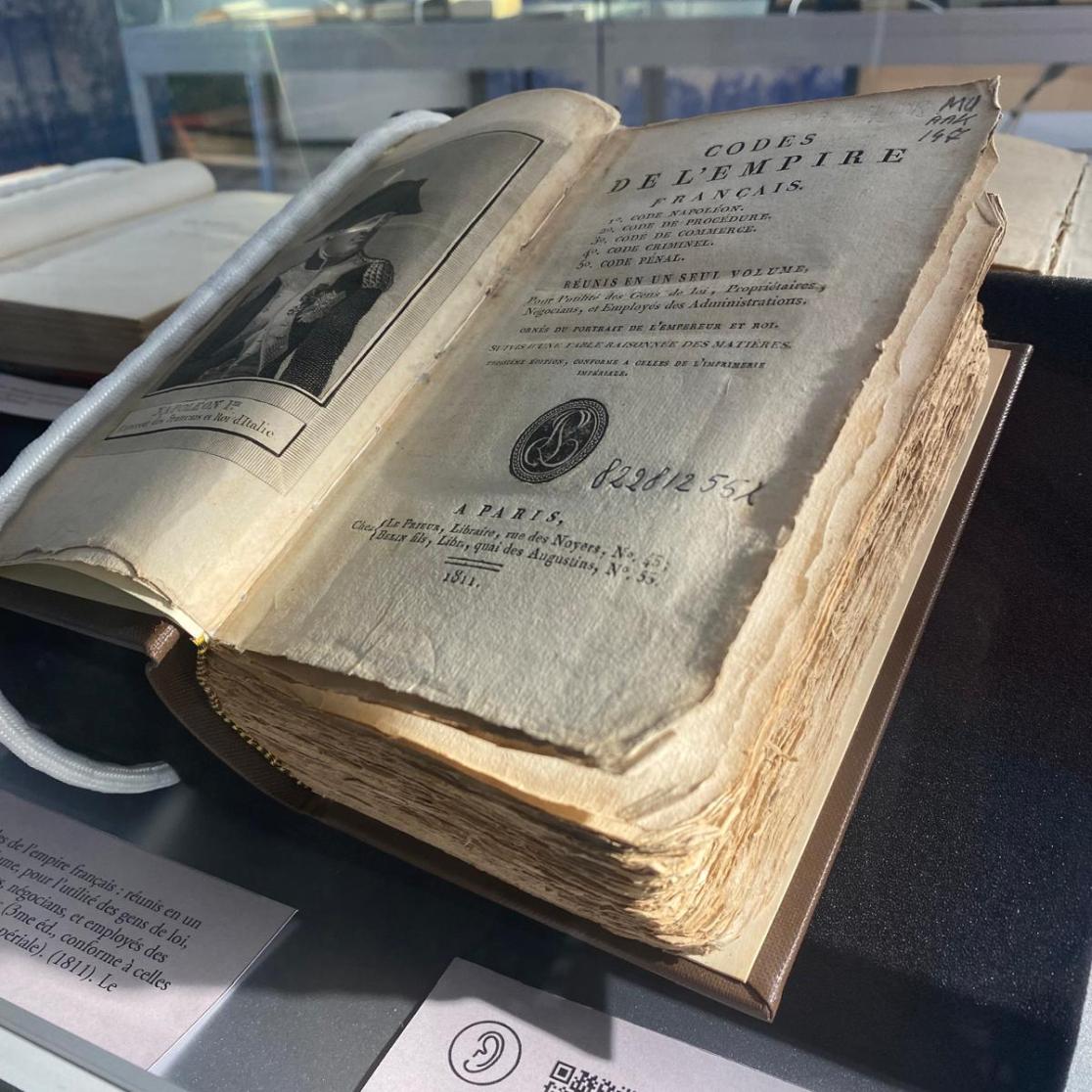

Law can be very abstract and/or very distant, and an object can offer a tangible materialisation that can assist to reduce some of the challenges in legal education. Maquettes, photographs, diagrams, all can be considered objects of study and learning. Performance can provide an object of study. A visit to a museum can activate the senses. Exhibits can provide useful objects to study the law, such as the experiences with Victor Hugo and the Grimm Brothers, at Maastricht University. Many visitors at the Louvre are impressed by the Code of Hammurabi. Law students, when visiting that museum, can see that code as a conduit for the 289 laws it presented, seeing the object as a means to transfer knowledge, triggering awareness of its size and imposing shape and resulting in a representation of power and authority. There are different objects that can be used in a PBL habitat. Books, libraries, desks, outfits, all can be considered objects. Legal historians, for example, can think of a medieval gloss as a prime object, recognising its value as a tool through centuries when developing legal education. Looking at a gloss could assist in explaining how these scholarly products worked and how they were directly linked to the letter of the law. A gloss captures the law, while also being a tool to see the law.

The Actors

The PBL environment benefits from assigning different roles to students in the learning experience. The discussion leader plays an important role, for example. When introducing an object one of the students could be assigned as object guardian or object facilitator. That role can help in providing a suitable interaction with the object. A prop of an artifact encountered at a criminal scene, in a criminology problem, can benefit from an object guardian, who can interact with the object, for example, holding the prop of the artifact in the hand, to see how a criminal might have used it. Students can at that point reflect on what expertise is needed to investigate a criminal case. Instructors and students, alike, should introduce objects into the PBL classroom. This claim is not new! Already in 1928, John H. Wigmore, noted in A Panorama of the World’s Legal Systems, that the pictorial method could be of value in the teaching of comparative law. At that time he asked: “Who would have thought that the dry history of Law could be enlivened with pictures?” Wigmore then added that, in his volume, “the pictures present the edifices in which Law and Justice were dispensed (whether temples, palaces, tents, courthouses, or city-gates); the principal men of law (whether kings, priests, legislators, judges, jurists, or advocates); and the chief types of legal records (whether codes, statutes, deeds, contracts, treatises, or judicial decisions). By these aids, the narrative attempts to reconstruct some realistic impressions of the legal life of these peoples. Subsequent study of the book-learning about the details of these [legal] systems can thus be made more attractive and intelligible.”

The Corollary

PBL and OBL should be amalgamated in the classroom as a means to further develop legal education. Together they offer an additional dimension to active learning and therefore can enhance the legal education experience for everyone in the classroom. In addition, that amalgamation can be fun!

A. Parise

Agustín Parise (Buenos Aires, Argentina) is Associate Professor of Law at the Faculty of Law of Maastricht University. He received his degrees of LL.B. (abogado) and LL.D. (doctor en derecho) at Universidad de Buenos Aires (Argentina), where he was Lecturer in Legal History during 2001-2005. He received his degree of LL.M. at Louisiana State University Law Center (USA), where he was Research Associate at the Center of Civil Law Studies during 2006-2010.

-

Solo l’Italia? Gabry Ponte’s Eurovision song underlines striking limitations to Italy’s effective control over its cultural heritage imagery

The staging of San Marino representative’s performance during Eurovision might be in violation of Italian cultural heritage law – yet, the principle of territoriality prevents Italy from taking effective legal action.

-

The Legal Philosophy of Role-Playing Games

In this blog, Michele Ubertone aims to show that the cognitive and rational skills that are involved in role-playing are also at the heart of legal practice. Cognitive developments we all go through in the early stages of our lives, train and develop a distinctive cognitive ability, a form of...

-

Academic Curiosity in the Realm of the Law

Legal science evolves in many ways. Academic curiosity is an important drive in that evolution, opening paths of exploration and igniting awareness on the needs of society. Curiosity–in all its forms–deals with exploring, discovering, and learning towards acquiring new knowledge. Its etymology...