Redrawing borders

Professor of Philosophy of Public Health Klasien Horstman and Belgian artist Marlies Vermeulen have won this year’s Mingler Scholarship for their project Bacteria & Borders. Experimental cartography between art, lab & (daily) life. They plan to study and make tangible the realities of infectious diseases in border regions.

“It feels quite liberating, as though it invites illegal activity – national authority seems very far away,” says Klasien Horstman about growing up close to the German border, in the Northern part of the Netherlands. This notion of borders and transgression has stayed with her. She’s become a philosopher working across disciplines and studying public health, a field which in itself has to grapple with the blurred borders between medical expertise, clinical realities, socio-economic processes, cultural repertoires, and so much more.

Five years ago, Maastricht University's Care and Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI) established a collaboration between researchers from the humanities, social sciences, law, medical microbiology and infectious diseases prevention with a shared commitment to the public character of health, rather than just the purely clinical aspect. In this transdisciplinary environment, Horstman focuses on the sociocultural dimension of disease control.

Crossing the t’s and borders

Transdisciplinary research is a ubiquitous buzzword, but it takes hard work and a great deal of openness and curiosity to make it work properly. “It took us three years to understand each other,” laughs Horstman. “We’re trying to investigate the role of individual behaviour, involvement of the state, the democratic legitimation of top-down prevention strategies, etc. – and we generate recommendations how to get citizens involved in the process.”

Given her background and the degree of mobility between Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany around Maastricht, Horstman quickly became interested in the spread of infectious disease in border regions. “Bacteria and viruses don’t care about borders – but in a way they do! My colleagues showed that an outbreak of the zoonotic Q Fever with thousands of cases in the Netherlands led to mass cull of livestock – but there was no outbreak in Germany, even though it happened very close to the border.”

Covid-19 is the wheezing elephant in the room, especially in a city as international and defined by borders as Maastricht. “States respond differently – and the impact is most clearly observable in border regions. In Germany, you have to wear a facemask in shops, in the Netherlands you don’t. That means that Germany might be safer, but it definitely means that Germans come to Maastricht to shop without the inconvenience of having to wear a facemask…”

So, can different national approaches explain different mortality rates? “Of course, closing borders and containment measures make a difference. At the same time, Germany has massively tested people and therefore got many positives back from young people who didn’t develop symptoms; the Netherlands didn’t include nursing home deaths in the statistics, while Belgium has. So there might well not be that much of a difference after all.”

Constructive Constructivism

What researchers can find depends on what they are looking for how and where. “Of course, bacteria and viruses and their effects on tissues are real,” Horstman explains. “At the same time, I believe that we construct the reality of diseases.” The way we define and investigate disease is deeply intermingled with the paradigms and technologies we use to do that.

This view avoids dichotomies between culture and biology (or body and mind, for that matter). It may be hard to see how this applies to ‘biological facts’ such as bacteria and viruses, and, as Horstman notes, “people find that approach more plausible in softer medicalised concepts such as, say, attention deficit disorder or depression. But is does apply to viruses and bacteria as well.”

Since science is so deeply intertwined with culture, “we need more anthropologists and sociologists in disease control!” Horstman naturally has a vested interest here – but studying the ‘cultures of science’ can have far-reaching practical ramifications: “Medical microbiologists in the hospital had developed a test for antimicrobial resistance that was 14 hours faster, but clinicians didn’t use it. They asked us to look at it, so we conducted interviews and observational studies.”

It turned out that the test results became available an hour before the end of their shifts; therefore practitioners were reluctant to change patients’ antibiotics regimes without being able to monitor the effects personally. “There were other factors too, like the nondescript name of the test, but it was basically a case of the fifth floor not understanding how the fourth floor works and thinks.”

Horstman studies – and communicates to scientists and practitioners – the biosocial complexities of healthcare practices. Which is by no means an invitation to relativism: “There are more and less clever ways of dealing with these complexities… Some measures work better than others, but it is really important to take the constructed character of disease realities into account, as this also points to our own responsibility for the landscape of health and diseases, including the epidemics that we are confronted with.”

The Mingler Scholarship is made possible by the Academy of Arts in collaboration with the Young Academy of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) and is financially supported by the Niemeijer Foundation.

Horstman and her colleagues Alena Kamenshchikova, Petra Wolffs, Christian Hoebe, and Volker Hackert will team up with artist Marlies Vermeulen for Bacteria & Borders. Experimental cartography between art, lab & (daily) life.

Mapping up the border cases

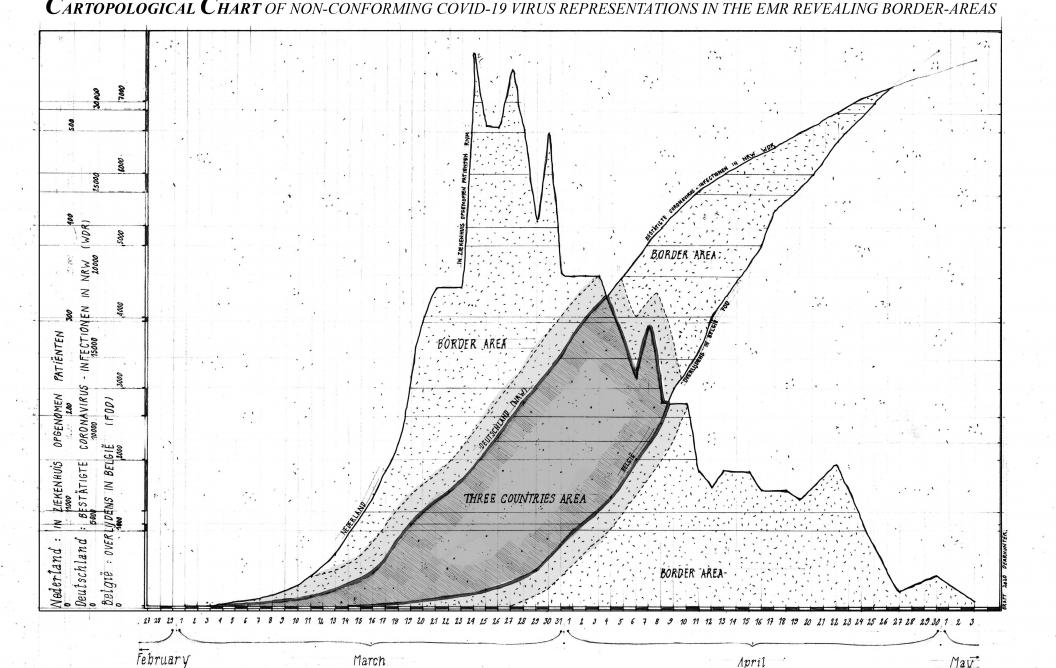

BioSocial complexities are multiplied in border regions. In Bacteria & Borders, Horstman and cartography artist Marlies Vermeulen will try to understand how borders help or hamper disease control measures in the Belgian-Dutch-German border region. They will conduct ethnographic and statistical research into the flow of people, vaccination patterns, and the spread of infectious diseases.

“It might very well be that national borders play no role at all. Maps of the spread of diseases usually show a national average and stop at the border. That doesn’t reflect the multiple realities of these border regions.” Therefore, Vermeulen will translate those empirical findings into a cartographic art. “An artistic experience might help epidemiologists, and people in general, to rethink how borders and infectious disease control work.” Horstman and Vermeulen have been awarded the Mingler Scholarship 2020. “We’ve been working in this direction for quite a while. It has always been very relevant for border regions – but the pandemic certainly has made it even more. Collaboration between science and arts on this subject is very exciting and inspiring.”

by: Florian Raith

Also read

-

Europe Day

To celebrate Europe Day on 9 May, FASoS student Lisa travelled to Brussels to meet with five of our inspiring alumni who are currently shaping European policy and advocacy. In this video, they share why Europe Day matters, how it’s celebrated in Brussels, and what the idea of Europe means to them.

-

The Green Office Catalyses Circularity Projects’ Autonomy

This semester, the Green Office cultivated the untapped potential of the Community Garden and the Clothing Swap Room. We hope that these Circularity Projects will operate under autonomous, functional organisations by this time next year, with continued support from the Green Office and the SUM2030 team... -

Evidence-based health tips for students: the science of eating healthy

In the upcoming months, we’ll share tips on Instagram for our students on how to live a healthier life. Not just a random collection, but tips based on actual research happening at our faculty. The brains behind this idea are L ieve Vonken and Gido Metz, PhD candidates at CAPHRI, the Care and Public...