Panic: what you should (or shouldn’t) do

Professor Koen Schruers was set on studying schizophrenia after graduation – until he was asked to participate in PhD research on panic. He was fascinated. One in four people will suffer a panic attack at least once in their lives, and one in thirty will develop a panic disorder. The phenomenon can be studied with experiments: just the kind of research method that suits Koen. In his book Paniek en hoe het aan te pakken (Panic and how to tackle it) he offers some practical tips. One of the most important pieces of advice? Schruers: “Breathing into a paper bag does not work.”

According to Koen Schruers, anyone can get panic disorder – some might just be more prone to it than others. If you’re suffering from a panic attack, symptoms can come on suddenly and reach their peak within a minute: there is no such thing as a slow panic attack. Panic attacks can be the root cause of avoidance behaviours. After all, a panic attack will make you feel like you’re dying, and that’s something we want to avoid as much as possible. But the better we understand panic as a phenomenon, the better we can help patients.

Peaking in your twenties

A panic disorder differs from other psychiatric conditions in that it often emerges acutely. Depression, for example, starts gradually and develops progressively. A panic disorder is not always preceded by a traumatic experience. But panic sufferers often have experienced a long period of stress, for example at work or in a relationship. The straw that breaks the camel's back differs for everyone.

Panic symptoms typically begin when people are in their mid-twenties. At this age, people are still studying or finishing their studies. It does not come as a surprise that this is the peak age for panic: many changes are happening simultaneously. “New social relationships, moving to a new home, a new area of study, the transition to professional life: it’s a lot”, Schruers explains. “It’s a very fun period! But it can also make you vulnerable.” Extended periods of stress can lead to panic disorders for some students, which can hugely impact student life. “Students with regular panic attacks start avoiding social situations – right when meeting new people plays a huge role in this stage of life.”

Schruers himself notices this in his lecture halls as well. “Some students don’t come to lectures anymore because of their anxiety. Plus, students with panic disorders usually sit in the back of the hall, so they can leave quickly if they feel a panic attack coming up.” The pandemic was actually great for this group of students, says Schruers. “They could follow all lectures safely from home. So far, there hasn’t been any evidence of panic disorder rates increasing during COVID. Existing panic disorders don’t seem to have gotten worse either: students with panic disorders didn’t have to do things they were scared of during lockdowns.”

Dealing with panic

In his book, Schruers wants to emphasise two aspects: more people are suffering from panic disorders than you might think, and there are good treatments to help people deal with this. Especially if you start early. “By starting early, you can prevent a lot of suffering. A single panic attack doesn’t mean someone has a panic disorder, of course. But if they happen regularly, you will need treatment – even if the frequency ebbs and flows. Still, if you’ve been walking around with a panic disorder for longer, it can still be treated! It will just take a little more effort.”

Schruers mainly helps patients with panic disorder by using exposure therapy, meaning he actively triggers panic symptoms. During this therapy, a panic attack is mimicked to eventually make the symptoms disappear entirely. “This treatment is unpleasant and exhausting but works extremely well and relatively quickly. People who have had just one exposure therapy session, are usually quite motivated to continue – precisely because they notice that it works very well.”

People who have had just one exposure therapy session, are usually quite motivated to continue – precisely because they notice that it works very well.

Koen Schruers

Panic tips

What can you do if, for example, you see a fellow student having a panic attack? “Don’t just wave a paper bag in their face. People still think those kinds of things help, but they don’t. Always ask the person in question whether or not they know what’s happening to them. If they’ve had a panic attack before, they’ll probably recognise the symptoms and know what’s best for them. Advise them to visit their GP and tell them about their panic attacks.”

“If they don’t recognise what’s happening, ask them if they’re experiencing tightness in the chest, shortness of breath, nausea or tinnitus. These are the most common symptoms of a panic attack, so if the answer is yes, then tell them that’s what they might be experiencing. Do the symptoms worry you? Immediately call the emergency number, 112. It can be difficult to tell the difference between a panic attack and a heart attack.”

The key to avoiding panic disorders is staying healthy: sleep well, eat well, plenty of exercise, and foremost be careful around drugs. “Unfortunately, there’s no specific way to prevent panic disorder,” says Schruers. “But if you’re vulnerable to panic and want to prevent symptoms? Keep your stress levels in check. Exercise regularly and keep stress at a minimum. These small things tend to have a huge impact.”

Text: Jodi Bel. Photography: Katja Waltmans

Koen Schruers is also the spokesperson of the Academic Centre for Anxiety, Compulsion and Trauma, a collaboration between UM and Mondriaan that's been running for over 35 years. He was a co-author of over more than 180 international scientific publications. His book ‘Paniek en hoe het aan te pakken’ (Panic and how to tackle it) was recently published.

Also read

-

Fresh air

Newly appointed professor Judith Sluimer (CARIM) talks about oxygen in heart functioning and the 'fresh air' the academic world needs.

-

Özge Gökdemir and Devrim Dumludağ reveal differences in competitive behaviour between women in the Netherlands

Economists and spouses Dr Özge Gökdemir and Professor Devrim Dumludağ conducted a study for Maastricht University that reveals differences in competitive behaviour between women in the Netherlands. Their findings will be published soon in a scholarly journal. Here, they give us a sneak peek.

-

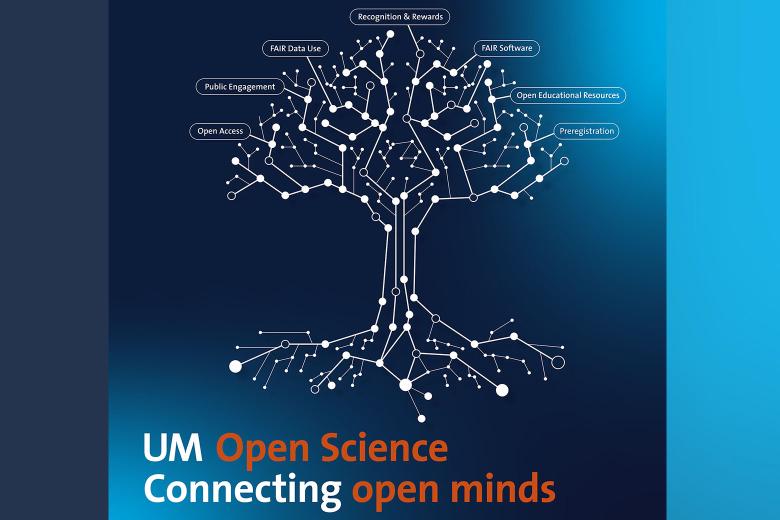

What exactly is Open Science?

Open Science proposes openness about data, sources and methodology to make research more efficient and sustainable as well as bringing science into the public. UM has a thriving Open Science community. Dennie Hebels and Rianne Fijten talk about progress, the Open Science Festival and what...