How does the universe taste?

In the Netherlands, you can hardly travel further than from Groningen to Maastricht. Gerco Onderwater did it; he swapped the most northern Faculty of Science and Engineering for the most southern one. Here, he investigates the flavour of the universe while guarding the flavour of the Maastricht Science Programme. On May 31, during his inaugural lecture, he provided a pre-taste of his work in Maastricht.

How does the universe taste? "Delicious," according to Gerco Onderwater. It tastes probably just as delicious as the beer he drank on a Groningen terrace in 2022 with two fellow physicists from Maastricht. “They asked if I might be interested in a position as dean of the Maastricht Science Programme (MSP). Before I knew it, I received an invitation from Maastricht University for an interview about the vacancy.”

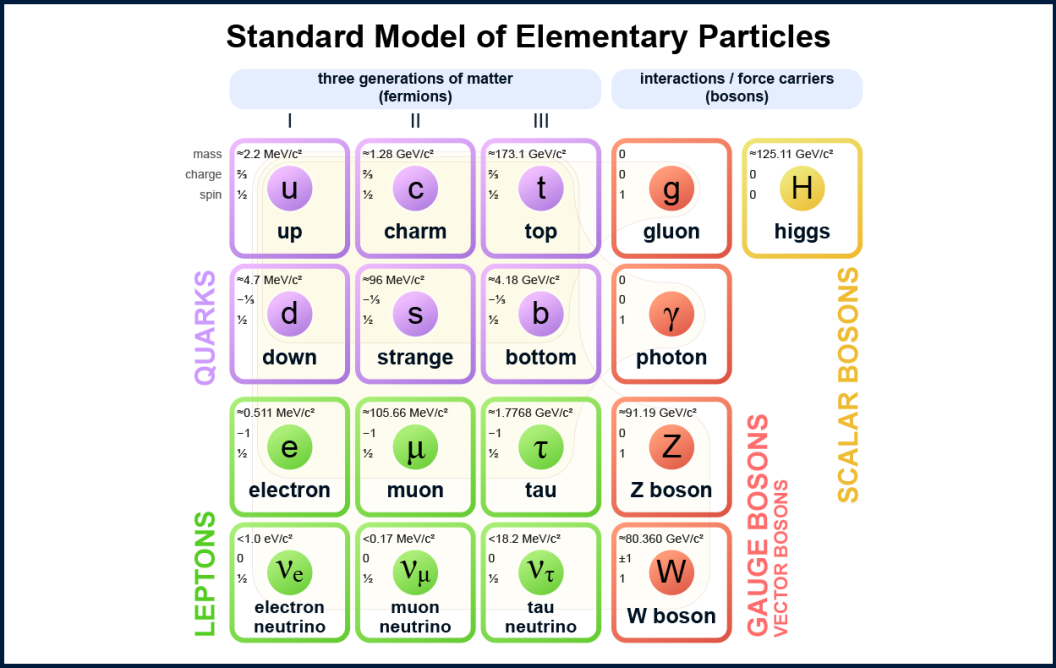

Onderwater in Maastricht, like Groningen, examines elementary particles that physicists refer to as "flavours." He focuses on the standard model of particle physics, which predicts with unparalleled precision how elementary particles combine to generate matter, molecules, life, and, in short, everything we see around us. "That theory has been tested in all kinds of ways since the middle of the last century and has been confirmed again and again, sometimes with an unprecedented accuracy of up to 13 decimal places." So, the theory must be right. Despite the precision, the answer may be "no" or, as Onderwater puts it, "almost."

Ten billion

Although the standard model is capable of making many accurate predictions, it sometimes misses the mark completely. "If you measure the ratio between matter and light particles in the universe and compare your observation with the predictions by the two standard models, that of elementary particles and that of cosmology, there is a factor of 10 billion difference between the two," says the scientist. Onderwater and his colleagues at MSP and the Gravitational Waves and Fundamental Physics research group are trying to explain the difference.

The researchers investigate the properties of the six leptons (including the electron). These elementary particles are found in groups of two, each with a distinct flavour. "The leptons are considered unbreakable; they strictly adhere to physical rules regarding the symmetry of particles." However, physicists prefer these particles to break the rules of physics. "That could explain the discrepancy between the measured and expected ratios of matter and light particles. That is why we hunt for signs that the leptons aren't so well-behaved after all and are breaking the symmetry rules slightly."

That could explain the discrepancy between the measured and expected ratios of matter and light particles. That is why we hunt for signs that the leptons aren't so well-behaved after all and are breaking the symmetry rules slightly.

Colleges

Maastricht University's three Liberal Arts & Sciences Colleges, like leptons, have their own distinct flavour. "It has to stay that way," states Onderwater. Nonetheless, he works with the deans of University College Maastricht and University College Venlo to achieve greater homogeneity. "We greatly strengthened cooperation and coordination in the field of education, such as admission, examination, and complaint procedures. By aligning these, we can aid each other and make it easier for students to take classes at other colleges. In terms of content, we all maintain our individual identities."

According to Onderwater, Dutch university colleges, including those in Maastricht, have an image problem. "It is an Anglo-Saxon educational approach that is expensive due to its small scale. Among the various physics-related bachelor programmes in the Netherlands, high school students must search hard to find a university college that offers physics courses, such as the Maastricht Science Programme. The typical Dutch mentality of 'appearing regular since that's strange enough' also fails to attract Dutch students. We shall consequently endeavour to raise awareness about University Colleges and Liberal Arts & Sciences in high schools."

Robust

Onderwater was director of education at the Groningen Faculty of Science and Engineering, overseeing programmes in mathematics, physics, and education. He notices disparities between the Faculties of Science and Engineering at both universities. "Groningen is an old university with strict regulations, whereas Maastricht is more dynamic. FSE here is new and growing like mad, so it is understandable and beneficial that not everything has crystallised yet. But, because of this fast growth, education must be organised more closely in order to be robust enough to cope with the growth." In Maastricht, Onderwater hopes the university can draw further upon his experience in organising education.

Also read

-

Working at UM: “a life-changing experience”

"I am proud that our new Circular Plastics group published its first completely in-house research," Kim Ragaert says. She founded the research group three years ago, when she moved to Maastricht. Her work has laid the foundations for many innovations in the field of plastic recycling, and she is...

-

Bridging the gap between technology and clinical practice

Lee Bouwman, a vascular surgeon and endowed professor of Clinical Engineering, specialises in the implementation of groundbreaking healthcare technologies. The key to success, he says, lies in the collaboration between engineers and clinicians. This approach has already resulted in a range of...

-

Anna Wilbik’s goal is to exploit the real value of data to the max

On April 19, during her inaugural lecture, Anna Wilbik explained how we can squeeze out the whole potential of data to the last drop.