Economics and a sustainable world: what to teach our students?

In a rapidly changing world faced with environmental challenges and social inequalities, the role of economics education in shaping future leaders is more critical than ever. If we aspire for a sustainable future, it becomes essential to (re)evaluate what we teach our students about economics and its implications for the world we live in.

Traditionally, economics education has emphasized mainstream economic theory including the principles of economic growth, market efficiency, rational choice and maximizing individual utility. The rapidly growing literature on sustainability and inequality shows that such mainstream approaches are often not well suited to find answers to questions like how we should organize our society to make it future-proof and how can we reach a sustainable society. Other approaches in economics such as ecological economics, post-Keynesian economics and many other schools of thought and more radical approaches are entering the sustainability debate.[1] In this blog I plea for a more diverse, more pluralistic approach to economics teaching. Not only as an afterthought but truly integrated from the outset.

I will discuss this alongside the question of whether the world economy can still experience economic growth and at the same time reduce the ecological footprint. This enters the discussion on whether decoupling of economic growth and environmental damages is possible, on green growth and degrowth.

Green growth versus degrowth

Recently I gave a lecture on the basics of economic growth, and I started, as traditionally is done so in mainstream economics, by discussing the first principles of neoclassical growth theory. That theory investigates the relationship between the growth of economic income (measured by GDP) and the use of capital, labour, and technology. The relation of economic growth to environmental sustainability and social equity did not enter the first part of my lecture. Being unsatisfied with that, I subsequently discussed the relation between economic growth and climate change by showing the drivers of CO2 emission in the world, the so-called Kaya identity.

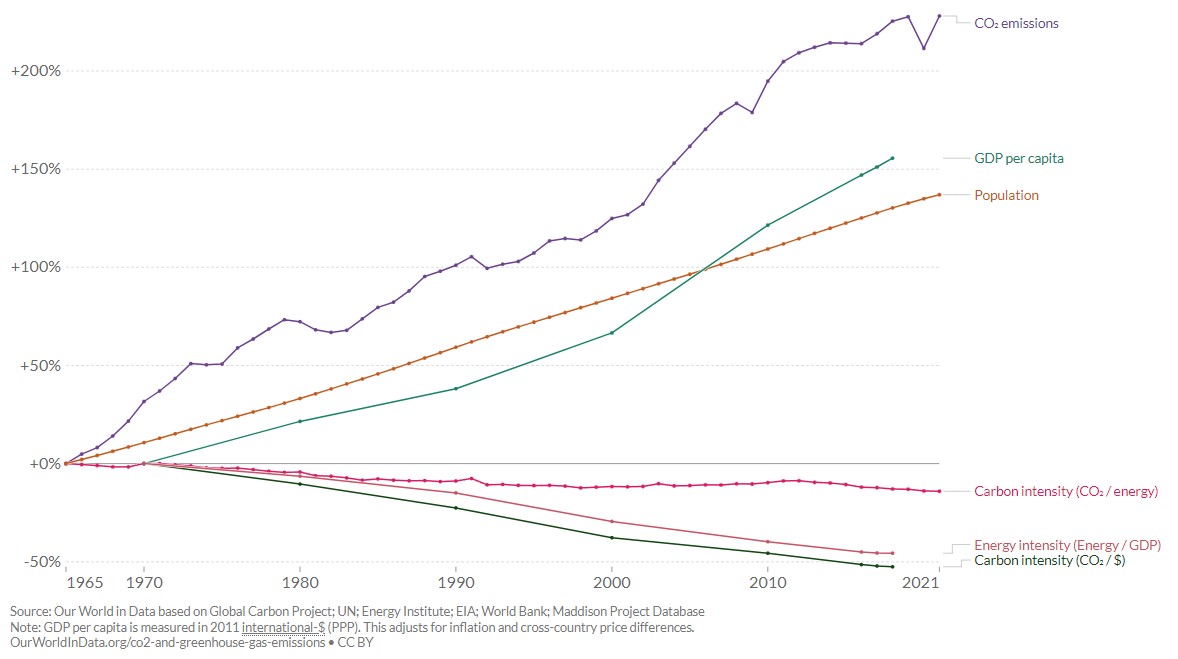

This identity simply decomposes the total growth of worldwide CO2 emission into various underlying components: average GDP per capita and the world population (both combined result in total GDP), the energy use per unit of GDP (energy intensity) and the CO2 emission per unit of energy use (carbon intensity). Total emission is then the multiplication of all these four terms. Total emissions will obviously decrease if all terms decrease. If some terms increase, the others have to decrease faster to decrease total emissions. The graph shows this decomposition and the development of these four terms through time. Time is on the horizontal axis and total growth since 1965 is on the vertical. The line at the top shows the index on total worldwide CO2 emissions. To reduce total CO2 emissions, either population growth or GDP growth per capita should be reduced, or different technologies should be developed to reduce energy and carbon intensity. The figure clearly shows that until now, population growth and growth of GDP per capita far outweigh the improvements in lowering energy intensity and lowering carbon intensity such that the resulting total CO2 emissions are growing continuously (let us ignore the impact of the Covid crisis). There is a slight slowdown in growth in most recent years, and despite worldwide investments in green technologies such as wind and solar power and in increasing energy efficiency, total CO2 emission is still growing at a fast pace. To reach the goals of the Paris Agreement, CO2 emissions have to peak before 2025 and be reduced by at least 45 per cent in 2030 compared to 2010 levels and even to net zero in 2050. In this graph, this implies the total CO2 emissions have to get reduced to just above the 100% line in 2030. That is a reduction of 50% in less than 7 years from now!

Advocates of green growth propose increased investments in existing green technologies and innovation efforts to significantly reduce carbon and energy intensities. However, considering the substantial investments already made in green technologies and examining the current trends as shown in the graph, achieving such a transformation would require an immense and extraordinary reduction in carbon and energy intensity. This ambitious path seems to rely heavily on unknown benefits stemming from yet-to-be-discovered technologies. While it is crucial to pursue research and development in search of these breakthroughs, it appears unavoidable to me that achieving climate goals may also necessitate a shift towards reducing GDP per capita: degrowth.

The concept of degrowth prompts discussions about economic paradigms and the essential relationship between human economies and the natural environment. Embracing degrowth challenges the traditional notion of continuous economic expansion and questions the assumption that continuous growth can coexist with finite resources and ecological boundaries.

Why are alternative theories relevant?

The debate between green growth and degrowth extends beyond CO2 emissions and addresses the very structure of society. It touches on critical issues like the relationship between growth and prosperity, the future of capitalism, and the free movement of financial capital. Influential authors like Jason Hickel and Kate Raworth have engaged in this discussion, shedding light on its complexities.

This discussion goes far beyond mainstream economic theory, as it challenges the notion that sustainability and degrowth can be adequately explored within the mainstream paradigm. The traditional approach, which revolves around individual utility maximization in an idealized world, fails to account for real-world complexities. Factors such as limited information, imperfect competition, and various market distortions, such as increasing returns to scale, product diversification, and conspicuous consumption, are not able to provide answers that will bring us useful insights into how to find a path to a sustainable future.

Alternative economic theories, such as ecological economics and others, offer a fresh perspective by considering broader aspects often overlooked. While they may not provide direct answers, they stimulate the exploration of alternative pathways to sustainability. By incorporating these diverse viewpoints into the economics curriculum, we can cultivate a more holistic understanding from the very outset.

The way forward

To foster a sustainable world, economics education must integrate key principles of environmental sustainability, social equity, and long-term well-being. Students need to understand the concept of externalities, recognizing the (hidden) costs and benefits that affect not only the economy but also society and the environment. By incorporating these externalities into economic analysis, future decision-makers can make informed choices that align with sustainable practices.

Moreover, economics education should introduce students to alternative economic frameworks like ecological economics. This interdisciplinary approach challenges the traditional growth-centric model and emphasizes the interconnectedness of economic, social, and ecological systems. By integrating these perspectives, students can develop a deeper understanding of the complex relationships between human activities and the natural environment.

Furthermore, teaching about sustainable development and the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can create a sense of responsibility and global citizenship in students. Educating them on the importance of addressing poverty, inequality, climate change, and environmental degradation allows them to contribute to building a sustainable future.

Bringing pluralist economics to the core of our programmes also requires the development of excellent textbooks that provide such broader views. Although recently some very promising initiatives emerged such as the CORE book and Rethinking Economics, more such efforts are needed to foster the transition towards pluralist economics teaching at universities and beyond.

If we truly want to change the world, we should at least start by integrating the various contending perspectives into our educational programmes. I mean in the core programmes, not as a third-year elective as a sort of afterthought.

By way of references:

Rethinking Economics: https://www.economystudies.com/book/

The CORE economics book: https://www.core-econ.org/

Jason Hickel, 2020, Less is More, How degrowth will save the world, Cornerstone, UK

Kate Raworth, 2018, Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, Cornerstone, UK.

[1] For a short and nice overview of various schools of economic though, see John Harvey (2020), Contending perspective in economics, A guide to Contemporary Schools of Thought, second edition, Edward Elgar

.

Also read

-

Green light for UM participation in unique YUFE bachelor programme

The UM can start as a degree awarding partner in the new unique bachelor programme Urban Sustainability Studies offered by YUFE (Young Universities for the Future of Europe), an alliance of ten European universities. This week, the UM received a positive outcome of the macro due diligence assessment...

-

Professor Anouk Bollen-Vandenboorn appointed Knight in the Order of the Crown

Prof. Dr Anouk Bollen-Vandenboorn, Director of the Institute for Transnational and Euregional cross border cooperation and Mobility (ITEM) at the Faculty of Law, Maastricht University, was appointed Knight in the Order of the Crown on 3 July, during a formal ceremony at the Belgian Embassy in The...

-

Study Smart gets Dutch Education Premium

Maastricht University's (UM) interfaculty educational innovation project Study Smart is one of the three winners of the Dutch Education Premium 2025. This was announced on Tuesday during the Comenius festival in The Hague.