The art of doing maths

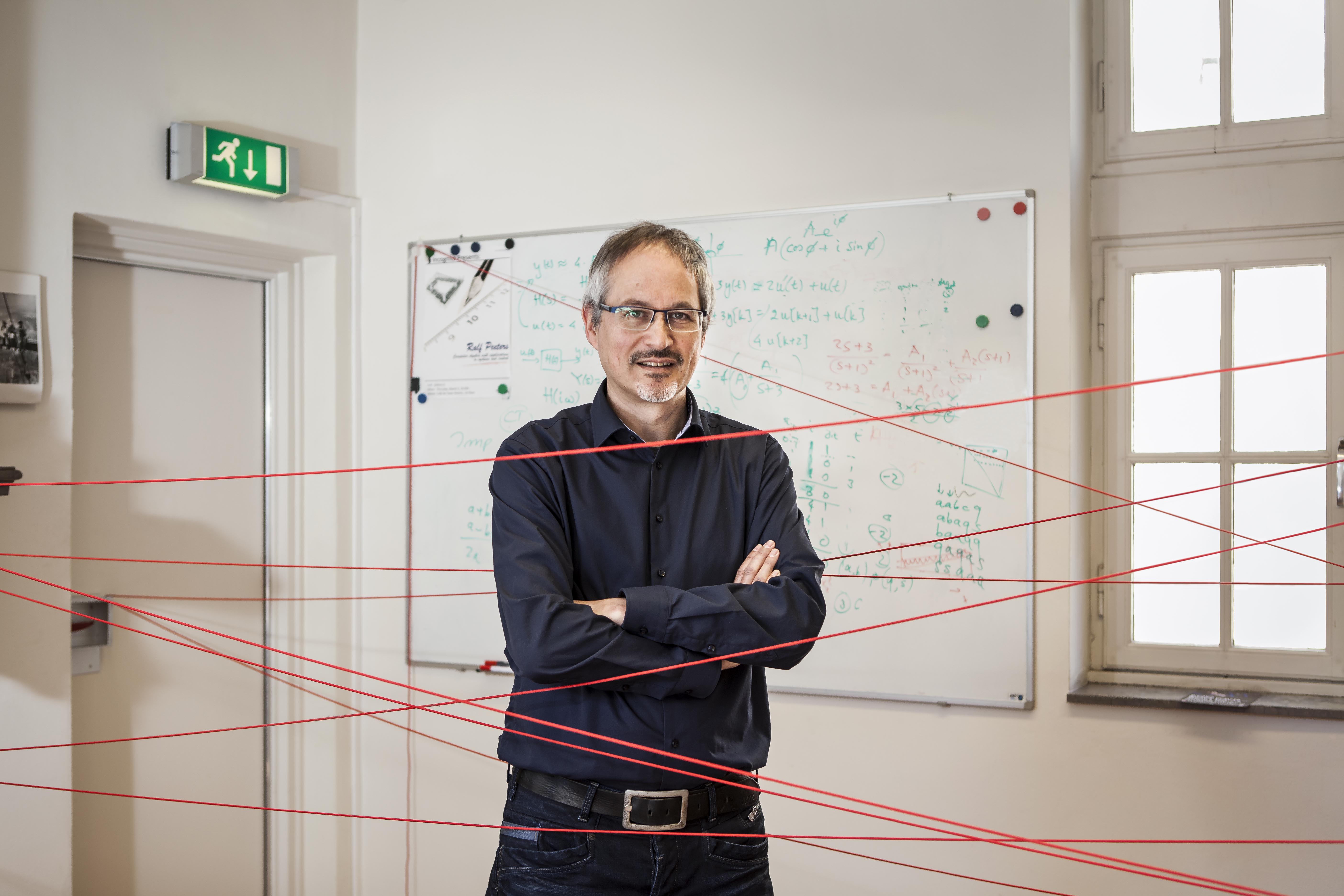

“Look at the person to your left and right: of the three of you, only one will graduate”, the lecturer said when Ralf Peeters attended his first lecture in Applied Mathematics in Delft. Thirty-six years later, Peeters is professor of Mathematics at Maastricht University. Without him, the Department of Data Science and Knowledge Engineering, which offers one of UM’s most successful study programmes, would have been swallowed up by another faculty long ago. Not that he’d ever say as much himself. Read on for portrait of a bridge builder, a puzzler, an art lover and, above all, a scientist.

In 2004 the matter was settled: the maths and computer science departments, including the Knowledge Engineering programme, would merge with the economics faculty. The university board had had enough of the infighting between the two groups, which had been going on ever since they were founded in 1987. Ralf Peeters doesn’t want to dwell on all that. He arrived at UM in 1994, two years after the launch of the Knowledge Engineering programme. “It was actually a data-science programme, although nobody used the term in those days. So we’ve been doing it for 25 years already”, he says, not without a touch of pride.

“Proper” maths

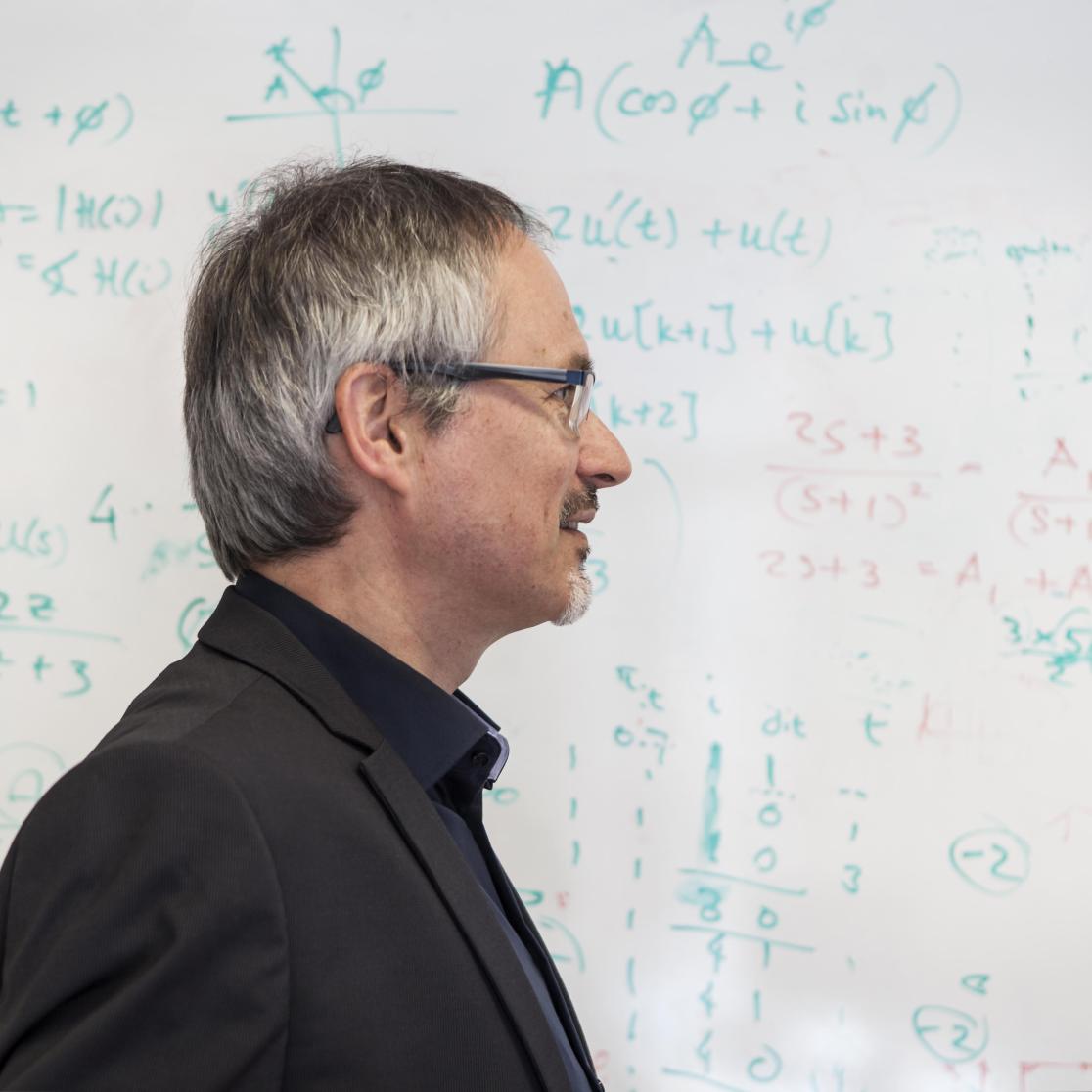

Peeters sailed through high-school maths. Although that wasn’t “real” maths, which he wouldn’t experience until he started at TU Delft. Popular perceptions aside, “proper” maths is not about doing sums. “For me it’s a kind of puzzle. It’s about seeing structures and patterns, how things relate to one another. When a mathematician finds a proof elegant, it’s not usually a proof involving lots of numbers. It’s about insight. It’s much more verbal than many people think.” And then comes the understatement: “Maths is something I enjoy.”

University was no harder; just different. “In those days nobody held your hand. I’d usually go to the first two lectures of a course and if the teacher didn’t bring much to the material, I wouldn’t bother anymore. In the last lecture I’d check how far they’d got and then pass the exam.” He started his PhD in Delft, and when his supervisor left after a year for the VU in Amsterdam, he went too. In 1994 he moved from Amsterdam to Maastricht, the birthplace of his father.

Advantage

Peeters has always been fascinated by concrete applications. This was what led him to choose Delft over a more general university that taught “pure” mathematics. “I’d be happy to discover a few new mathematical properties, but on the other hand I find it interesting to use advanced maths to get an actual application to work.” For instance, he has long collaborated with cardiologists in Maastricht. One of the PhD candidates he co-supervised with a cardiologist developed a mathematical method for detecting irregularities in patients’ heart signals with a high degree of accuracy. At the time, the state-of-the-art method was only 87% accurate. “And people had spent years developing it. Our very first attempt was already 85% accurate; then you know it’s got potential. We’d chosen a different starting point. That’s the art of it. You should only start tinkering around trying to improve something if you’ve really thought about the concept properly. That gives you an advantage over people who just crunch numbers. At some point they’re going to run up against the limits of their method.”

Mathematical application

For Peeters, the fun is in formulating questions differently, creatively. “Ideally you come up with your own puzzle and your own solution.” He also holds off on diving into his colleagues’ work, so as not to get trapped in their line of thinking. “But you don’t want to reinvent the wheel, so you have to eventually.” He recalls with a certain fondness developing an algorithm for a paper mill. The client wanted to know what caused the splodges during the paper printing process. Years later, ENT doctors studying the balance system were looking for a patient-friendly way of measuring torsion (the rotation of the eye around the line of vision). “When you zoom in on the structure of an iris with infrared light, it looks exactly like the images you get from extreme close-ups of pieces of paper. It’s funny to be able to pull software from eight years ago out of the cupboard and say, ‘Give this a try.’ The applications are very different, but as a mathematician you recognise the pattern when something is essentially the same problem.”

We scientists

He notices that in Maastricht, potential collaborators recognise the added value of having a scientist around. Colleagues elsewhere have often regarded his collaboration with the medical faculty with a combination of awe and amazement. But Peeters regularly sees miscommunications arising between scientists and their colleagues in the humanities. “When one of my colleagues asks a lot of questions in a group discussion, he’s seen as a difficult person who’s always complaining. That’s not how he means it. He just wants to get things straight: it’s this or it’s that. Not something in between; that’s inconvenient. We scientists have a different way of working. And sometimes also slightly different social skills, although of course that doesn’t apply to everyone.”

Minefield

Peeters himself was a shy child who preferred to stay in the background. His father was a history teacher and headmaster of a high school, but also active in the city council and in various foundations and boards. Perhaps some of this trickled down to Ralf, either at the kitchen table or genetically, because in order to preserve the independence of the DKE, in 2004 he waded into minefield of UM politics. “Nobody in maths or computer science wanted to merge with the economics faculty. If you don’t do research on anything related to economics, what would be the point for a mathematician or a computer scientist? I realise the board saw it as a solution, but it wasn’t the best choice for the programme or for the research groups. And ultimately not for the university either, given the current development of the science faculty.”

Soft club

For a university with no natural sciences can never be more than a “soft” club, scientists tend to think. And so Peeters became a lobbyist, bringing the maths and computer science groups together to envision a shared future. The board was receptive: on 1 May, the Faculty of Humanities and Sciences was officially renamed the Faculty of Science and Engineering. The time is finally ripe, he concludes: “This will only make the whole university stronger. And it would never have been possible if the exact-sciences programme had been abolished long ago. If you want good mathematicians, physicists and chemists, you have to offer an environment where they can do their own thing, and then facilitate collaboration with other disciplines. Because a physicist who belongs to the medical faculty is not seen as the real deal by other physicists.”

Setting boundaries

He has never had second thoughts about pursuing a career in maths. But he did discover that those who make a career out of their hobby need to learn to set boundaries. It was a hard lesson, and one Peeters learnt early on. “These days I’m all right with an overflowing calendar. When it gets too much, I’ll plan something fun and relaxing, like going to a concert.” At a concert he finds he can put the work and the looming deadlines to one side. “That I can do only if it’s something I really enjoy, like music.”

Twists and turns

Art is another source of relaxation. In his view, maths and art are not so far removed. Art often deals with structures and patterns. Maths is a creative process and can also be very playful, with surprising twists and turns – as long as you have the time for it. “That’s the problem with our subject in the modern university. Good research takes time. First you have to sort out all the puzzle pieces. That takes an hour and then you have to go and do some management task, or teach. The next time you have to start by sorting out your puzzle pieces again. It’s very ineffective. Academics don’t complain about their teaching load because they don’t like teaching, but because it puts pressure on their research.”

A few years ago he and his wife began collecting all kinds of art. “I like things that leave room for your own imagination. It has to say something, but not everything.”

Also read

-

From Study to Startup: The story behind Famories

When Lennie and Neele graduated, while many of their classmates were busy fine-tuning CVs and stepping into roles at top companies, they took a detour by recording podcasts with their grandmas. What began as a charming way to cherish family memories has blossomed into Famories, a vibrant startup...

-

Riding the waves of change: From a summer vacation to a life that feels as good as it looks

For SBE alumna Victoria Gonsior, one spontaneous decision: trying surfing sparked a journey of self-discovery, leading her to redefine success, embrace joy, and build a career that aligns deeply with her values. From quiet beaches in Sierra Leone to coaching sessions rooted in purpose, Victoria...

-

SBE researchers involved in NWO research on the role of the pension sector in the sustainability transition

SBE professors Lisa Brüggen and Rob Bauer are part of a national, NWO-funded initiative exploring how Dutch pension funds can accelerate the transition to a sustainable society. The €750,000 project aims to align pension investments with participants’ sustainability preferences and practical legal...