Overcoming the pitfalls of anachronisms – and why this matters to all of us

Every now and again, and especially when redesigning a curriculum, the question regarding the role and place of legal history in said curriculum is brought up. And rightly so. That is why the Open University Law School (UK) organized an online event on 15 December entitled Diversity, Dilemmas and Discoveries: Legal History in the Curriculum. The problem with conferences like these is that, albeit very interesting, they have a relatively high level of ‘preaching to the converted’. Nevertheless, I do believe that what was discussed during this conference is of some importance also to those not already convinced, so I would like to share some key points with my fellow legal educators. More concretely I would like to explain how we can overcome the pitfalls of anachronisms and why this is useful knowledge for everyone teaching law.

Unintentional vs intentional anachronisms

Most of you know about that Starbucks cup that mysteriously ended up in Game of Thrones. Some might call this anachronistic, but – apart from the fact that Game of Thrones is not based on history, it’s fantasy – I would simply call it for what it is: a mistake, something the makers of Game of Thrones did not intend to happen. However, in January 2020 Laura’s father, who spent the majority of his life working at the Waterford Crystal factory, complained that the film ‘Little Women’ was no good because of the incorrect appearance of a Waterford Crystal bowl. (Her mother loved the film, so the trip to the cinema was not entirely wasted.) This is what I would call an ‘unintentional anachronism’. Contrary to the makers of Game of Thrones, the makers of Little Women intentionally used the crystal bowl. However, they thought they were using glassware correct for the period pictured, but unfortunately, they were off, with the result that someone not as well versed in the specifics of Waterford Crystal as Laura’s father might from now on think that the type of Waterford Crystal used in Little Women was available in the 1870ies. Obviously, this is problematic, because it is wrong.

But does it always work this way? In the film Marie Antoinette (2006), director Sofia Coppola tried to picture her protagonist allegedly through her own eyes; a naïve teenager, who had never known a different world than the lavish one she moved in, but who had to shoulder a heavy duty for a teenager: the duty to produce an heir to the throne. In one shot, we see the young queen sitting in her boudoir with in the background a pair of converse sneakers. Say what? However, this deliberate anachronistic use of a pair of shoes that obviously did not exist in eighteenth-century France was meant to illustrate Marie Antoinette’s naïveté, her teenage outlook and her relative innocence, despite a lifestyle that was highly inappropriate given the problems France faced at the time. This is what I call ‘intentional anachronisms’ and if well used, they can be very illuminating.

The importance of context

In order to do so, we need context. Imagine a map, which just shows streets. No street names, no indication of land marks, no specific buildings, nothing. Just the streets. Would you be able to tell what place on earth you are looking at? Maybe, if the streets pictured form a very specific grid pattern like Manhattan, or if the map shows a river with very specific bend, like the Thames in London. But that is because you are able to connect what you see to what you already know. In other words, you are familiar with the context. However, would you be able to distinguish the street pattern of Zwolle from that of Tilburg, without any background knowledge? Again, that is why we need context. Context allows us the recognize anachronisms and to put them to good use. Outlander’s costume designer Terry Dresbach dressed Caitríona Balfe in outfits based on twentieth-century high fashion designs from the likes of Dior and Balenciaga to highlight that Claire herself is an anachronism; a twentieth-century woman thrown back 200 years in time. However, for someone not aware with this context, Claire is dressed very odd indeed. Beautiful, but odd.

Anachronisms in legal education

Why is this all relevant to us, academic lawyers?

Anachronisms are primarily caused by the conceptual and normative frame(s) of reference of people, which includes assumptions regarding the functioning and purposes of law, caused by e.g. cultural and socio-economic factors, including education. The same phenomenon appears in the exercise of comparative law, a discipline which has become essential in our increasing globalizing world. However, what good will it do us if we are only capable of looking at another jurisdiction through the lens of our own?

Legal historical education and especially the awareness regarding the pitfalls of anachronisms can help us here. Legal history, or history in general, can serve as a mirror. Through the careful use of anachronisms, you can see the present reflected in the past and the past in the present. Why do we look in the mirror in the morning? Because we want to know whether our hair looks good, whether the earrings I chose actually go well with my sweater. In short, because I want to gain some knowledge and dispel incorrect assumptions. It gives me the possibility to correct mistakes, even if it only concerns badly selected jewellery.

Legal history will teach us the origins of certain thought processes and the way (and the reason) why certain thought processes influenced a legal system in a certain place at a certain time. Actively avoiding the pitfalls of anachronisms subsequently trains us to be aware of our ingrained assumptions and biases, up to the point that it will become a second nature when dealing with current global diversities.

Mistakes in dealing with others will always be made. Legal historical training and the skill to recognize, avoid ánd use anachronisms will help us to correct them. And that is a skill that is undoubtedly useful to us all.

| More blogs on Law Blogs Maastricht |

M.F. Lenaerts

Mariken Lenaerts (1981) is Universitair Docent bij de capaciteitsgroep Grondslagen van het Recht. Zij is gespecialiseerd in rechtsgeschiedenis, rechtsfilosofie en familierecht. Haar huidige onderzoek gaat over de vraag of en in hoeverre de ethiek van permacultuur in het recht geïmplementeerd kan worden.

-

Democracy and Nihilism: denouncing contemporary populist rhetoric

In this piece, I will use two memes to begin to unpack what I think is the common denominator of contemporary populist rhetoric. I will explain that the real substance of this rhetoric is the creation of a false moral equivalence, revealing a nihilism. Finally, I will suggest how this false moral...

-

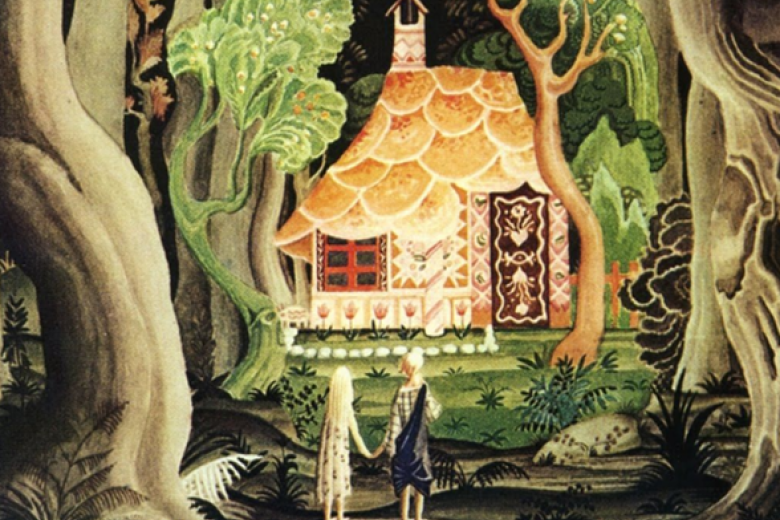

Legal science through the lens of fairy tales

Fairy tales, when understood as manuals of behaviour that are shared within the household, can serve as a means to study and understand the law at a specific time and space. This claim is not new. The Grimm Brothers, the renowned scholars Friedrich C. von Savigny (1779-1861) and John H. Wigmore...

-

Law, armed conflicts, and empowerment: instructors and students in a path to peace

Armed conflicts are not something new, sadly. They emerge in different parts of the globe, at different times, and due to different reasons. Three reflections follow on the role of legal education in the context of armed conflicts, inviting for paths for instructors and students to pursue peace...