From paradise to enterprise, aggression rules small populations.

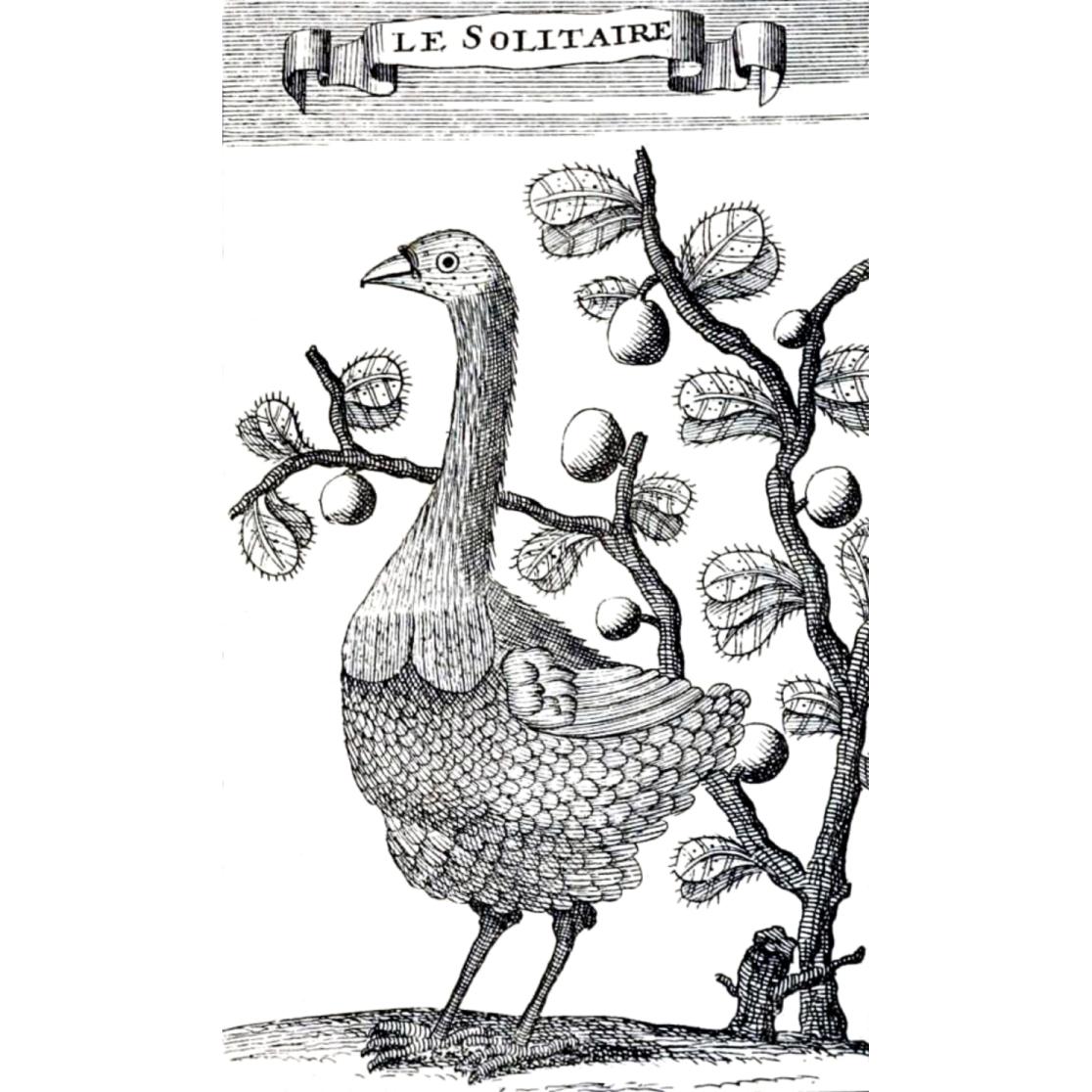

Imagine living on an island that loses about 90% of its land area due to natural disasters, putting your food supply at risk. How would you ensure there is enough space and food for yourself and your offspring? On the island of Rodrigues, birds like the Solitaire tackled this challenge with aggression, even evolving weapon-like adaptations on their wings.

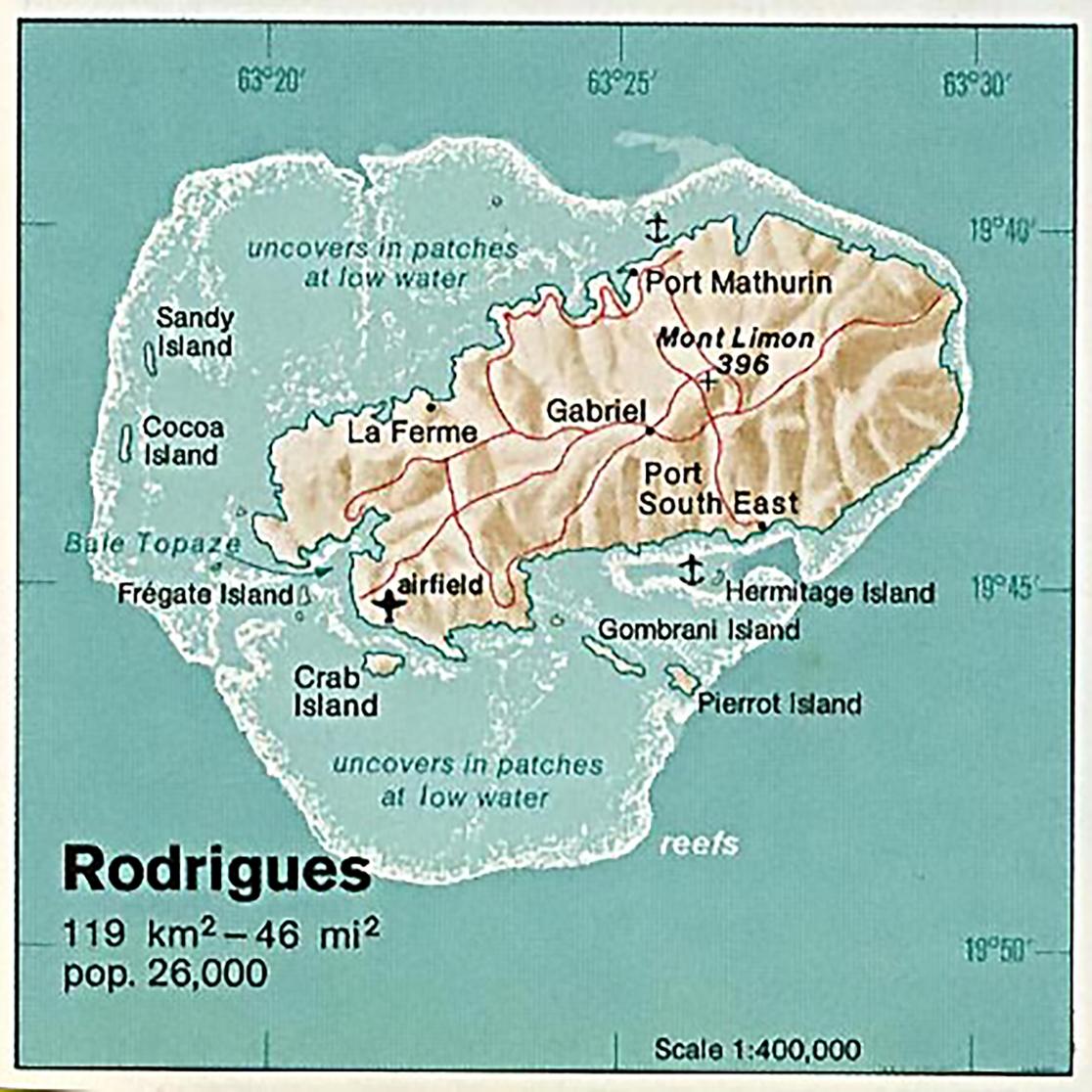

Your research destination is not always just around the corner, especially if you are a palaeontologist interested in extinct tropical birds like the peaceful Dodo and the aggressive Solitaire. Professor in Palaeontology at the Maastricht Science Programme, Leon Claessens sometimes travels to their former habitats on the islands of Mauritius and Rodrigues, located in the middle of the Indian Ocean. These islands have all the natural beauty you would expect from a tropical paradise: dazzling white, sunlit beaches, palm forests, and idyllic waterfalls.

Paradise

Much like in Maastricht, on Rodrigues fossils can be found in limestone. While the limestone in Maastricht once formed the seabed of a vanished ocean, the limestone cliffs on Rodrigues lie along its beaches. Undoubtedly, there are worse places to work. “The atmosphere on this remote island is very pleasant, far from the aggression that once characterised the life of the Solitaire. Moreover, Rodrigues holds significant potential for new discoveries,” says Claessens. “The journey to Rodrigues takes more than a day. First, a flight to Mauritius, and then a journey onwards to Rodrigues by propeller plane.” Research in places like Mauritius and Rodrigues is not cheap; Claessens funds it with grants from sources like National Geographic.

Eaten away

Humans only recently inhabited Rodrigues. A group of French explorers were the first to set foot there in the late 17th century. One of them, François Leguat, documented the Solitaire. He noted that these metre-high birds were extremely aggressive. “The bird would not last long. Early settlers had consumed most of the island’s resources within two centuries, and the Solitaire went extinct in the 18th century,” says Claessens.

Leguat’s descriptions continue to intrigue researchers. Why were all these birds, both male and female, so aggressive? Large-scale aggression is not typically an effective strategy, after all. “It consumes energy and may lead to injuries or even death,” Claessens says. "Many Solitaires suffered bone fractures during their lifetimes, which we can now observe in fossils as silent witnesses of their violent interactions. The bones in their wings contain protrusions near what would be our wrists. These are hard thickenings we call boxing balls. With these weapons, the birds would attack one another.”

Ice age

Interdisciplinary research from palaeontologists, evolutionary biologists, and geologists reveals that Rodrigues’ land area has fluctuated significantly. During ice ages, it expands, but afterwards, as sea levels rise because of melting ice, the area rapidly diminishes by as much as 90%. The Solitaire population finds itself in trouble. The most aggressive birds retain their territory and dominate. They pass on their genetically determined aggression to their offspring, and eventually, all the birds become aggressive. Since this phenomenon repeated after each ice age, the population remained aggressive.

Corporate culture

The research produced a remarkable finding: the scientists could mathematically demonstrate a critical threshold. Once this threshold is crossed, aggression becomes an irreversible dominant trait of that population. Claessens dares to extrapolate the findings to humans, but notes this is a personal speculative reflection. “Perhaps our mathematical model could apply to any structure that can be modelled as a population. Assume a corporation needs to downsize dramatically, and individuals with hostile behaviour manage to avoid being sacked. If the organisation continues to shrink, only unpleasant people will remain, resulting in an aggressive corporate culture. When the organisation grows again, that aggressive culture will grow with it.”

Claessens’ office is filled with fossils, some still undescribed, and packed in plastic boxes. Some are fossils he recently collected with students in Maastricht’s ENCI quarry. Obviously, there is plenty of work to be done. However, a palaeontologist is always in need of new study material. “Fortunately, fieldwork at ENCI is scheduled for the summer of 2025, and the next trip to Mauritius is in the planning stages.”

Text: Patrick Marx