This is a practical guideline how to pass on your information to our secretariat for (social) media distribution.

Since early 2020, the Data Protection as a Corporate Social Responsibility (DPCSR) research project at Maastricht University’s European Centre on Privacy & Cybersecurity (ECPC), has explored ways to improve transparency in the digitalized world. Data subjects (for example, consumers, internet users, etc.) all too often do not understand the information provided to them by organizations about how their personal data is processed.

In research carried out under the direction of Prof. Dr. Paolo Balboni, we found that transparency can be increased by using data protection icons. Icons, small images which represent or depict data processing activities, can be included in online and app information notices, payment forms, and registration forms to call the attention of users to certain processing activities. Last year we therefore developed a set of icons with the aim of facilitating users’ understanding of how their data is used, with specific reference to five domains, which tend to present inherent high risks for the rights and freedoms of individuals:

- Data used for marketing purposes (Marketing Icon);

- Data used to evaluate certain personal aspects of individuals and make automated decisions (Fully Automated Processing Icon);

- Data transferred to a country outside the European Economic Area which does not guarantee a high level of protection (Transfer Icon);

- Data shared with other parties, including third parties in exchange for direct profit and/or value (Data sharing in Exchange for Direct profit/Value Icon);

- Processing of sensitive data (Sensitive Data Icon).

You can read more about the UM DPCSR Icons Version 1.0 here.

To understand the effectiveness of the UM DPCSR Icons we created, we developed a 10-minue online survey directed towards EU citizens age 13 and older. The survey is available in the English, Dutch, French, German, Italian, and Spanish languages. The purpose of the survey is to help the researchers obtain a better understanding of the usefulness of the icons we have created, which specifically depict potentially high-risk processing activities. The results of the survey will ensure that the UM DPCSR Icons are comprehensible to a variety of people belonging to different nationalities, education levels, ages, and privacy-awareness levels.

We kindly ask you to support and contribute to our research project by agreeing to take the survey, which can be found here.

Acting together, we can improve transparency, and in doing so, better the digital world!

If you have any questions about the survey or the UM DPCSR Research Project, please contact Prof. Dr. Paolo Balboni at paolo.balboni@maastrichtuniversity.nl.

Authors:

Paolo Balboni, Professor of Privacy, Cybersecurity, and IT Contract Law at the European Centre on Privacy and Cybersecurity (ECPC) within the Maastricht University Faculty of Law

Kate Francis, PhD candidate at the European Centre on Privacy and Cybersecurity (ECPC) within the Maastricht University Faculty of Law

17 May 2021

Maastricht, The Netherlands

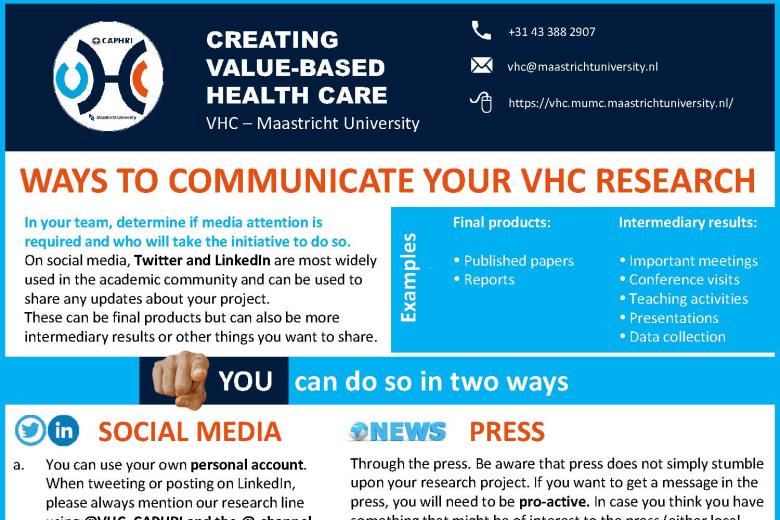

VHC Communication

Guidelines

Ways to communicatie your VHC research

In your team, determine if media attention is required and who will take the initiative to do so. On social media, Twitter and LinkedIn are most widely used in the academic community and can be used to share any updates about your project. These can be final products but can also be more intermediary results or other things you want to share.

VHC toolbox

You can use these documents :

Diversity and inclusivity are at the core of the YUFE identity. We strongly encourage students with all backgrounds and identities to apply for the Student Forum to truly foster an inclusive YUFE community.

What is YUFE?

The Young Universities for the Future of Europe (YUFE) alliance is a partnership consisting of ten young research-intensive universities from ten European countries. The YUFE alliance, together with its four associate partners from the private and NGO sector, aims at bringing radical change in European higher education by establishing itself as the leading model of a young, student-centred, non-elitist, open and inclusive European University. A unique ecosystem linking universities to communities, YUFE is based on cooperation between higher education institutions, the public and private sector, and citizens across Europe. The YUFE proposal has received the top-score as part of the European University Initiative (EUI) of the European Commission (97/100), which will pilot the development of revolutionary concepts such as European Degrees, the European Student Card and inclusive mobility for all.

What’s the YUFE Student Forum?

How will YUFE stay young, student-centred, and non-elitist? The YUFE Student Forum has a lot to do with this! The purpose of the Student Forum is to make sure that the perspective of the students is always present in the realisation of the YUFE vision. From the outset, students have played a central role in all stages of the alliance – from proposal preparation, to now the implementation phase. Each partner university of the YUFE alliance has committed to have of three students participate in the Student Forum and the working groups that will oversee YUFE’s implementation. The YUFE Student Forum representatives are important in co-leading and co-creating the YUFE project and vision. This is also reflected with the participation of students in the whole governance structure of YUFE, even on the level of the Strategy Board, where the President of the YUFE Student Forum acts as a co-chair. As a student-member, you will co-develop the YUFE Student Journey, YUFE in the city-initiatives, etc. The Student Forum will elect a steering Board that is responsible for the daily management of the Forum.

What’s your role?

As a YUFE Student-member for UM, your role will take many forms. You will:

- actively work with your fellow UM student-colleagues and your Institutional Coordinator to communicate relevant YUFE activities to UM students and gather and communicate their input to the wider YUFE Student Forum;

- work with the representatives of all other YUFE partners as part of the YUFE Student Forum to ensure that the input of students is reflected in the development of the alliance

- actively participate in one of the eight thematic YUFE working groups, for instance in ‘Diversity and Inclusivity’ ‘YUFE in the city,’ or the ‘Student Journey’, which will make the YUFE vision a reality.

An ideal candidate would be able to communicate in English, has good communication and organisation skills (or be motivated to improve these) and is open-minded. Moreover, you need to be able to dedicate sufficient time (min. 10 hours/month as an indication) and be willing to engage in occasional European travel. An open and inclusive mind and the ability to take initiative is key. However, most importantly, you will need to demonstrate your motivation, enthusiasm and commitment to make truly European Higher Education a reality. Language guidance can be offered if necessary. It is important to keep in mind that this is a voluntary opportunity, but that all expenses due to YUFE (e.g. travel costs) will be compensated by your university.

Once you are selected, you will receive an invitation for a two-day ‘Welcome meeting’. This meeting will consist of an opportunity to get to know each other and to get a thorough introduction to the YUFE-project, its vision and its deliverables, but also to acquire useful skills like intercultural communication through training sessions. After this, an election of the Student Forum Board will take place.

Are you ready to take part in making history and change the education landscape of Europe?

Send us your application, including a CV and a motivation letter (max. 1 page), by 1 June 2021 at veronique.eurlings@maastrichtuniversity.nl using the subject line “YUFE Student Forum Application”.

More information can be received via the YUFE website or by contacting YUFE institutional coordinator at UM: Veronique Eurlings.

Skills

(glocal) participatory action

Rubric

Civic engagement is about making a difference by promoting the quality of life in the communities through political and non-political processes. The activities that the individuals engage in are personally life enriching and socially beneficial to the community (https://www.aacu.org/initiatives/value-initiative/value-rubrics/value-rubrics-inquiry-and-analysis). The Association of American Colleges and Universities (AACU, 2005) created a value rubric to evaluate student’s learning. The civic engagement value rubric is used to assess knowledge, attitudes and skills from benchmark to capstone level. The rubric captures the six criteria: Diversity of communities and cultures, analysis of knowledge, civic identity and commitment, civic communication, civic action and reflection, and civic contexts/structures. As an example of the civic contexts/structures criterion students that reach the benchmark level experiment with civic contexts/structures by trying them out to see what fits. Students reaching the milestone level demonstrate the ability to work actively in community contexts. At the capstone level the student “demonstrates ability and commitment to collaboratively work across and within community contexts and structures to achieve a civic aim” (Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2009))

Teaching examples

- Service Learning

- Design Project Based Interventions

- Learning teaching activities | (glocal) participatory action

References

- Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2009). Civic engagement VALUE rubric. https://www.aacu.org/initiatives/value-initiative/value-rubrics/value-rubrics-inquiry-and-analysis

- Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2005). Liberal education outcomes: A preliminary report on student achievement in college. https://www.aacu.org/leap

- Sklad, M., Friedman, J., Park, E., & Oomen, B. (2016). ‘Going Glocal’: a qualitative and quantitative analysis of global citizenship education at a Dutch liberal arts and sciences college. Higher Education, 72, 323-340.

Change agency

A change agent is a person or group that works on a change programme and/or that encourages people to change their behaviour or opinions. Universities can encourage their students to become a change agent by providing them the opportunity to take on a leadership role and conducting their own research.

Kay and colleagues (2010) define students as change agents as actively engaged with the process of change by taking on a leadership role. Furthermore, they are engaged with the institution and their subject areas, Students build change on evidence-based foundations.

The Global Institute for Lifelong Empowerment (GiLE) defines Students as Change Agents as allies in making necessary changes both in the academic environment and in society at large. It encourages students to think and be more active and by creating and innovating and they become the change they demand to see. https://www.gile-edu.org/articles/ethics-and-responsibility/involved-engaged-constructive-students-as-change-agents-today/#

Rubric

Goal 3.3 of the APA Goals for Undergraduate Major in Psychology is described as adopting values that build community at local, national, and global levels. The rubric lists basic (foundation) indicators and advanced (baccalaureate) indicators for each of the six aspects from goal 3.3. At the foundational level of goal 3.3b students are expected to “recognize potential for prejudice and discrimination in oneself and others” whereas students will “develop psychology-based strategies to facilitate social change to diminish discriminatory practices” at the baccalaureate level (Halonen et al., 2020). “Applying psychological principles to a public policy issue and describing the anticipated institutional benefit or societal change” as well as “seeking opportunity to serve others through volunteer service, practica, and apprenticeship experiences” are baccalaureate indicators of goals 3.3e and 3.3 (Halonen et al., 2020).

Teaching examples

- Collaborative online intercultural learning

- Service learning

- Work-integrated experiential learning

- Improv theatre for character strengths

- Design projectbased interventions

- Students as Change Agents

- Teaching learning activities | Change agency

- Honours+ | Faculty of Law

References

- Cambridge University. (2022). change agent. In Cambridge Business English Dictionary.

- Kay, J., Dunne, E., & Hutchinson, J. (2010). Rethinking the values of higher education-students as change agents?.

- Halonen, J. S., Nolan, S. A., Frantz, S., Hoss, R. A., McCarthy, M. A., Pusateri, T., & Wickes, K. (2020). The challenge of assessing character: measuring apa goal 3 student learning outcomes. Teaching of Psychology, 47(4), 285–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628320945119

Connecting and collaborating

Rubric

The boundary crossing rubric by Gulikers and Oonk, (2019) can be used to assess interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary learning. It lists several aspects for the categories identification, coordination, perspective-making and learning from each other, and transformation. At the lowest level of perspective making and learning from each other the student “shows no action in stimulating other people to learn from each other”. At the C level the student reflects with team members on roles, contributions and development during the project, but does not actively transfer the results into improved performance of other people during the projects”. At the B level the student “initiates reflective actions between people involved in the project aimed at learning from the project (both process and content-wise)”. If a student reaches the highest A level he/she additionally “actively encourages other people’s learning in light of the project” (Gulikers & Oonk, 2019).

The Association of American Colleges and Universities (AACU, 2005) created a value rubric to evaluate student’s learning. The team work value rubric is used to assess knowledge, attitudes and skills from benchmark to capstone level. If a student reaches the capstone level of the contributing to team meetings criterion then he/she “Helps the team move forward by articulating the merits of alternative ideas or proposals” whereas the student “shares ideas but does not advance the work of the group” at the benchmark level (https://www.aacu.org/initiatives/value-initiative/value-rubrics/value-rubrics-teamwork)

Teaching examples

- Mini-internship

- Learning teaching activities | Connecting and collaborating

- Honours+ | Faculty of Law

References

- Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2005). Liberal education outcomes: A preliminary report on student achievement in college. https://www.aacu.org/leap

- Gulikers, J., & Oonk, C. (2019). Towards a rubric for stimulating and evaluating sustainable learning. Sustainability, 11(4), 969.

Conflict resolution

One key aspects within transformative engagement, is to work towards a peaceful word in a non-violet way. Furthermore, conflict resolution education also supports developing social competencies as cooperation, empathy, creative problem solving, social cognitive skills, and relationship skills.

UM Teaching examples and assessment

- Moot Court

- Improv theatre for character strengths

- Honours+ | Faculty of Law

- Client Consultation Competition | Faculty of Law

- ICC Mediation Competition | Faculty of Law

References

- https://www.wiley.com/en-ie/The+Handbook+of+Conflict+Resolution+Education:+A+Guide+to+Building+Quality+Programs+in+Schools-p-9780787910969

Design thinking

Related constructs/concepts

- innovation,

- unlearning,

- evaluation and feedback-seeking,

- resourcefulness,

- future mindedness,

- creating new value

UM Teaching examples and assessment

Attitudes/Values

Courage

Courage is the ability to meet a difficult challenge despite the physical, psychological, or moral risk involved in doing so (‘Courage’, 2020). Courage is the voluntary willingness to act, with or without varying levels of fear, in response to a threat to achieve an important, perhaps moral, outcome or goal. The two generally agreed upon components of courage: threat and worthy or important outcome. Courageous actions are an amalgamation of character strengths to include bravery, persistence, integrity, and vitality (Peterson and Seligman, 2004). There are different types of courage, which are still under debate. Overall is agreed upon at least two types: Physical courage and moral courage.

Teaching examples

- Improv theatre for character strengths | PSY3383 | Improv(e) your Soft Skills

- Service learning | ECA | Maastricht Mediation Clinic

- Honours+ | Faculty of Law

Resilience

Resilience is the ‘process and outcome of successfully adapting to difficult or challenging life experiences’ (“Resilience”, 2020). Literature has indicated resilience reflects three attributes: resistance, as the ability to maintain functionality in an adverse situation; recovery, the process to return to the pre-situation state, and robustness the capacity to withstand perturbations (Grafton et al., 2019).

Measurement

A possible measurement scale for individual resilience is the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (Connor & Davidson, 2003) with 25 items or the Brief CD-RISC scale (Campbell‐Sills & Stein, 2007) with 10 items. Example items of the scales are, “able to adapt to change”, “coping with stress can strengthen me”, and “can handle unpleasant feelings” (Campbell‐Sills & Stein, 2007; Connor & Davidson, 2003).

Another scale to consider is the Brief Resilience Scale (Smith et al., 2008). “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times” and “it does not take me long to recover from a stressful event” are two items of the scale (Smith et al., 2008).

Teaching examples

- Improv theatre for character strengths | PSY3383 | Improv(e) your Soft Skills

- Learning teaching activities | Resilience

- Honours+ | Faculty of Law

References

- Connor, K.M., Davidson, J.R., (2003).Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety, 18(2), 76-82.

- Grafton, R.Q., Doyen, L., Béné, C.,Borgomeo, E.,Brooks, K., Chu, L., Cumming, G.,Dixon, J., Dovers, S., Garrick, D., Helfgott, A., Jiang, Q., Katic, P., Kompas, T., Little, L., Matthews, N., Ringler, C., Squires, D., Steinshamn, S., Villasante, S., Wheeler, S. ,Williams, J., P.R. Wyrwoll, P.R. (2019). Realizing resilience for decision-making. Nature Sustainability, 2, 907-913

- Resilience. (2020). APA Dictionary of Psychology. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/resilience

- Smith, B.W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P. & Bernard, J. (2008). The Brief Resilience Scale: Assessing the Ability to Bounce Back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine,15,

Trust

A belief in the reliability, truth, or ability of someone or something (cf. interpersonal trust which relates to confidence between two persons and a willingness to be vulnerable to each other).

Critical hope

Being optimistic and future-oriented while having the ability to realistically assess one's environment through a lens of equity and justice while also envisioning the possibility of a better future. It differs from traditional concepts of hope, which cannot create the type of change that is needed in society because they lack the necessary critique and understanding of inequities. Critical hope means critically engaging in the past and present while simultaneously thinking about how to collectively impact communities through praxis. It is a continuous and

cyclical process of reflection and action. Educators have an important role in cultivating critical hope by navigating systems with a dual lens of attempting to contribute to positive social change while also orienting youth to the painful realities of the world and still seeing the possibilities for progress. Critical hope provides a resource to stay in these struggles in ways that are healthy and sustainable. Practicing critical hope requires an acknowledgement of the various ways in which hope has been used to both advance democracy, equity, and justice as well as to maintain the status quo (Bishundat, Phillip & Gore, 2018).

Scale/Measurement

The adult hope scale with its subscales agency (i.e., goal-directed energy) and pathways (i.e., planning to accomplish goals) can be used to evaluate the respondent’s level of hope (Snyder et al., 1991). Example items are “I energetically pursue my goals”, “there are lots of ways around any problem”, and “even when others get discouraged, I know I can find a way to solve the problem” (Snyder et al., 1991).

References

- Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., et al.(1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 570-585.

- Duncan-Andrade, J. (2009). Note to educators: Hope required when growing roses in concrete. Harvard Educational Review, 79, 181–194

- Bishundat, D., Phillip, D. V., & Gore, W. (2018). Cultivating critical hope: The too often forgotten dimension of critical leadership development. New directions for student leadership, 2018(159), 91-102.

Skills

Moral/ethical reasoning

Moral/ethical reasoning is defined as individual or collective practical reasoning about what, morally, one ought to do (Richardson, 2003). Moral reasoning indicates individual ethical sensitivity, and can be operationalized as individual moral reasoning capacity (Thorne, 2000). Moral reasoning is a component of moral judgement competence. It is therefore a key attribute to understanding students’ moral judgement development, including how to understand and interpret moral issues, how to understand the broader social world and differentiate the associated group-based claims on moral decisions, and how to participate in a diverse democracy through civic engagement (King & Mayhew, 2004; Nucci, 2006; Rest, 1988; Thoma, 2006).

Scales

Various scales have been developed to measure Moral Reasoning. Extensively used is the Defining Issues Test (DIT), based on Kohlberg’s theory of moral development. One of the six statements the participant is asked to rate notes as follows: “Should Heinz steal a drug from an inventor in town to save his wife who is dying and needs the drug?” (Rest et al., 1997).

Rubric

The Association of American Colleges and Universities (AACU, 2005) created a value rubric to evaluate student’s learning. The ethical reasoning value rubric is used to assess knowledge, attitudes and skills from benchmark to capstone level. It lists ethical self-awareness, ethical issue recognition, and understanding, application and evaluation of ethical perspectives as criteria. The benchmark level of the criterion ethical issue recognition notes that a “student can recognize basic and obvious ethical issues but fails to grasp complexity or interrelationships”. If students reach the milestone levels, they can recognize ethical issues when presented in a complex context or start to recognize interrelationships among the issues. The “student can recognize ethical issues when presented in a complex, multilayered (gray)context AND can recognize cross relationships among the issues” at the capstone level (https://www.aacu.org/initiatives/value-initiative/value-rubrics/value-rubrics-ethical-reasoning).

Teaching examples and assessments

- Moot Court | SSC2024 | International Law

- Work-integrated experiential learning | BMZ2022 | Schaarste in de Zorg

- Ethical dilemma | EBC2056 | International Financial Accounting

- Collaborative online intercultural learning | PSY4126 | Virtual Collaboration for the Common Good

- Service learning | ECA | Maastricht Mediation Clinic

- Legal philosophy | MET3003

References

- Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2005). Liberal education outcomes: A preliminary report on student achievement in college. https://www.aacu.org/leap

- Rest, J., Thoma, S. J., Narvaez, D., & Bebeau, M. J. (1997). Alchemy and beyond: Indexing the Defining Issues Test. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89 (3), 498-507.

Active listening

Active listening. The goal in active listening is to develop a clear understanding of the speaker’s concern and to clearly communicate the listener’s interest in the speaker’s message (Robertson, 2005). It requires techniques such as formulating appropriate questions, paraphrasing and summarizing(Robertson, 2005).

Scales

There are various scales that measure active listening. The Active Listening Attitude Scale (ALAS) measures the attitudes of people with respect to a person centered attitude and active listening. For example, “I tend to listen to others seriously”, “I’m the kind of person whom people feel easy to talk to”, and “I listen to the other person calmly, while he/she is speaking” are items of the scale (Mishima, Kubota & Nagata, 2000).

The Active‐Empathic Listening Scale (AELS) is an 11‐item scale, measuring active‐empathic listening across three dimensions: sensing (n = 4), processing (n = 3), and responding (n = 4) (Geiman & Greene, 2018; Bodie, 2011). An example item of the sensing dimension states, “I am aware of what others imply but do not say” and an example of the processing dimension is “I summarize points of agreement and disagreement when appropriate”. “I ask questions to show my understanding of others’ positions” is one item of the responding dimension (Bodie, 2011).

Rubric

Horton and colleagues (2013) designed a standardized counselling rubric including items of the categories: attending behaviours, verbal skills, and counselling structure. Students can range from 100% “meets expectations” to 50% “needs improvement” and 0% being “unsatisfactory”. For example, the item eye contact describes “maintained appropriate eye contact” as 100%, “initial eye contact, more time reading notes” as 50% and having “little eye contact” as unsatisfactory. For the item verbal tracking, the description for meeting expectations (110%) is “listened to patient and smoothly changed from one topic to the next”. Students score 50% when they consistently change topics ineffectively and occasionally interrupt. If they did not seem to listen to the patient or interrupted the patient’s story they scored unsatisfactory. For the item use of questions, 100% is described as “facilitative open-ended questions” opposed to 0% “mostly closed-ended and restrictive questions”.

Teaching examples

- Moot Court | SSC2024 | International Law

- Community-based learning | City Deal | Creating Knowledge Project

- Work-integrated experiential learning | BMZ2022 | Schaarste in de Zorg

- Mini-internship | BMZ2023 | Kijken in de Zorg

- Improv theatre for character strengths | PSY3383 | Improv(e) your Soft Skills

- Service learning | ECA | Maastricht Mediation Clinic

- Role-playing a briefing exercise | SSC3011 | Public Policy Evaluation & Analysis

- Teaching learning activities | Active listening

- Honours+ | Faculty of Law

- Bachelor Honours Programme | Faculty of Law

- Client Consultation Competition | Faculty of Law

References

- Bodie, G. D. (2011). The Active-Empathic Listening Scale (AELS): Conceptualization and evidence of validity within the interpersonal domain. Communication Quarterly, 59(3), 277-295.

- Horton, N., Payne, K. D., Jernigan, M., Frost, J., Wise, S., Klein, M., ... & Anderson, H. G. (2013). A standardized patient counseling rubric for a pharmaceutical care and communications course. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 77(7).

- Kylie L. Geiman, John O. Greene (2018), Listening and Experiences of Interpersonal Transcendence, Communication Studies, 10.1080/10510974.2018.1492946, 70, 1, (114-128).

- Mishima, N., Kubota, S., & Nagata, S. (2000). The development of a questionnaire to assess the attitude of active listening. Journal of Occupational Health, 42(3), 111-118

- Robertson, K. (2005). Active listening: more than just paying attention. Australian family physician, 34(12).

Emotion regulation

Emotion regulation is ‘the process by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express these emotions’ (Gross, 1998, p.275). The Emotion regulation tradition focuses on how a person can effectively manage his/her emotions to adapt to the social environment (Pena-Sarrionandia, Mikolajczak, & Gross, 2015).

Scale/measurement

The cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire or its short 18-item version can be used to measure the cognitive components of emotion regulation. The questionnaire includes the nine following subscales: Self-blame, Other-blame, Rumination, Catastrophizing, Positive refocusing, Planning, Positive reappraisal, Putting into perspective and Acceptance. For example, one item of the acceptance subscale states, “I think that I have to accept the situation” and another one states, “I think that I cannot change anything about it “. Additionally, two items of the planning subscale are as follows: “I think of what I can do best” and “I think about how I can best cope with the situation” (Garnefski &Kraaij, 2006).

UM teaching examples and assessments

References

- Garnefski, N., & Kraaij, V. (2006). Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire–development of a short 18-item version (CERQ-short). Personality and individual differences, 41(6), 1045-1053.

- Gross, J.J. (1998). Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74 (1), 224-237.

- Gross, J.J. & John, P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348-362.

- Pena-Sarrionandia, A., Mikolajczak, M., & Gross, J.J. (2015). Integrating emotion regulation and emotional intelligence traditions: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(160), 1-27.

Personal responsibility

Personbal responsibility is the willingness to make personal efforts to live by society's standards of behaviour, often centering on care and a concern besides self and family

Scale/measurement

Mergler and Shield (2016) constructed a 35-item scale to measure personal responsibility in adults. Some of the items state the following “I think of the consequences of my actions before doing something”, “I want my actions to help other people”, and “. I am aware of how my behaviour impacts on other people”.

References

- Mergler, A., & Shield, P. (2016). Development of the Personal Responsibility Scale for adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 51, 50-57.

Examples

- Honours+ | Faculty of Law

- Bachelor Honours Programme | Faculty of Law

Upstander skills

Choosing to intervene rather than ignore situations in which one witnesses high risk or potentially harmful behaviour. Relate to allyship skills: advocating and actively working for the inclusion of a marginalized or discriminated group in society, not as a member of that group but in solidarity with its point of view

Social responsibility

Social responsibility can be seen as the perceived level of interdependence and social concern to others, to society and to the environment It relates to personal development, and a personal search for meaning, to developing a sense of purpose, and to an aspiration to contribute beyond the self. Social responsibility ties in with normative competence and the development of (personal, professional and scientific) moral/ethical sensitivity, judgment and reasoning. It calls for empathy and integrity, and for upstander skills to give voice to one’s values. Finally, social responsibility can be fostered when learners can enact moral positions, when they have a role in improving society, supporting social justice, and working to solve collective problems.

Measurement

The Research Centre For Education and the Labour Market (ROA) collects data from UM alumni cohorts to assess their social responsibility five and ten years after graduation. For example one item asks, “to what extent does your current job have a broader societal impact” and another one, “how important is social responsibility in searching for another job” to evaluate the perceived (relative) importance of the role of social commitment in their careers. Moreover, graduates are asked for the extent to, which they (very) strongly influenced an organization from within to take greater social responsibility. On average, five and ten years after graduation 57% and 61% of UM alumni from the cohorts 2014/15 and 2009/10 indicate that they (very) strongly influence an organisation from within to take greater social responsibility (Aarts & Kuenn, 2021). Additionally, participants are asked to rank a number of aspects in terms of importance for their career. “Realizing social impact” is one of the aspects to be ranked. Moreover, the questionnaire asks for the extent that alumni have competencies related to social impact such as the ability to contribute to the development and/or implementation of new ideas, the ability to solve problems in new or unknown situations, and the ability to take societal issues and ethical questions into account when forming an opinion.

References

Aarts, B., & Künn, A. (2021). Maastricht University Graduate Surveys 2021. ROA. ROA Fact Sheets No. 001 https://doi.org/10.26481/umarof.2021001

Attitudes/Values

Moral integrity

Moral Integrity refers to moral consistency, honesty, and truthfulness with oneself and others (“Integrity”, 2020). In 1996, Carter identified three essential components of moral integrity: Moral discernment, which contemplates the ability to distinguish what is morally right and wrong; consistent behavior, as the ability to reliably act in different times and scenarios; and public justification, the ability to explain personal behavior in relation to moral convictions (Carter, 1996).

Measurement

A possible measurement to evaluate the degree of moral integrity of an individual is The Moral Integrity Survey (MIS) developed by Olson in 2002.

References

- Carter, S. (1996). Integrity. New York: Basic Books, a division of Harper Collins Publishers.

- Integrity. (2020). APA Dictionary of Psychology. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/integrity

- Olson, L. M. (2002). The relationship between moral integrity, psychological well-being, and anxiety. Charis: the Institute of Wisconsin Lutheran College, 2(1), 21-8.

Sense of purpose

Sense of purpose is a stable and generalized intention to accomplish something meaningful to the self and the world (Damon, Menon & Bronk, 2003). Literature has indicated that sense of purpose has three central aspects: awareness of purpose, as the subjective sense that one’s life has a meaning; awakening of purpose, as actively engaging in the process of exploring one’s purpose, and altruistic purpose, which refers to the intention of contributing to the greater good (Sharma, Yukhymenko-Lescroart & ZiYoung, 2018).

Scale

An emergent scale to measure this construct is the Revised Sense of Purpose Scale (SOPS-2) (Yukhymenko-Lescroart, & Sharma, 2020). An example item of the awareness of purpose aspect is “my purpose in life is clear”. “Recent activities are helping me to awaken to my life’s purpose” is one of the items to assess the awakening of purpose aspect. Lastly, “I want to spend my life making a positive impact on others” is one of the items to assess the altruistic purpose aspect (Yukhymenko-Lescroart, & Sharma, 2020).

References

Damon, W., Menon, J., & Bronk, K. C. (2003). The development of purpose during adolescence. Applied Developmental Science, 7, 119–128.

Sharma, G., Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M.A, & ZiYoung, K. (2018) Sense of Purpose Scale: Development and initial validation. Applied Developmental Science, 22(3), 188-199

Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M.A., Sharma, G. (2020). Examining the Factor Structure of the Revised Sense of Purpose Scale (SOPS-2) with Adults. Applied Research Quality Life, 15, 1203–1222.

UM teaching examples and assessments

- Community-based learning | BMZ2021 | Care in context

- Work-integrated experiential learning | BMZ2022 | Schaarste in de Zorg

-

Design project-based interventions | RIG4408 | Global Policy Challenges in Comparative Regionalism

References

- Damon, W., Menon, J., & Bronk, K. C. (2003). The development of purpose during adolescence. Applied Developmental Science, 7, 119–128.

- Sharma, G., Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M.A, & ZiYoung, K. (2018) Sense of Purpose Scale: Development and initial validation. Applied Developmental Science, 22(3), 188-199

- Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M.A., Sharma, G. (2020). Examining the Factor Structure of the Revised Sense of Purpose Scale (SOPS-2) with Adults. Applied Research Quality Life, 15, 1203–1222.

Empathy

Empathy represents the ability to understand individuals from their frame of reference rather than one’s own, or experiencing others’ feelings (“Empathy”, 2020). Research has shown that empathy has a cognitive and affective component. Cognitive empathy is the ability to identify, understand, and react appropriately to others’ emotional states and affective empathy is the ability to feel and share others’ emotions (Powell, 2018).

Rubric

The Association of American Colleges and Universities (AACU, 2005) created a value rubric to evaluate student’s learning. The Intercultural Knowledge and Competence VALUE Rubric is used to assess knowledge, attitudes and skills from benchmark to capstone level. The following is stated for reaching the benchmark level of the empathy criterion “views the experience of others but does so through own cultural worldview”. The descriptions for the milestone levels 2 and 3 note “identifies components of other cultural perspectives but responds in all situations with own worldview” to sometimes using more than one world view in interactions. Lastly, the capstone level is reached if the students “interprets intercultural experience from the perspectives of own and more than one worldview and demonstrates ability to act in a supportive manner that recognises the feelings of another cultural group.” (https://www.aacu.org/initiatives/value-initiative/value-rubrics/value-rubrics-intercultural-knowledge-and-competence).

The lifecomp framework lists three descriptions for the competence empathy that follow the model awareness, understanding and action (Sala et al., 2020). The first description is about acquiring abilities to read nonverbal cures to be aware of another person’s emotions, experiences and values. Tone of voice, gestures and facial expressions are examples of nonverbal cures. The second description is about the role of training in empathy, which helps to understand others’ emotions and reduce personal distress. Additionally, it is about the ability to take the other person’s perspective proactively. The action description, which is the third one, is about the ability to offer an appropriate response to others’ emotions to alleviate their distress (Sala et al., 2020).

Measurement

For assessing empathy, the Interpersonal Re-activity Index (Davis, 1983) or the Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (Reniers, Corcoran, Drake, Shryane, & Völlm, 2011) represent valid instruments to measure both cognitive and affective components.

The subscale empathic concern of the Interpersonal re-activity “assesses ‘other-oriented’ feelings of sympathy and concern for unfortunate others” (Davis 1983). For example, “I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me”, and “when I see someone being taken advantage of, I feel kind of protective toward them”, but also “other people's misfortunes do not usually disturb me a great deal” are items of the subscale (Davis 1980).

The following items are taken from the Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy: “I can tell if someone is masking their true emotion”, “I sometimes try to understand my friends better by imagining how things look from their perspective”, and “I often get emotionally involved with my friends’ problems” (Reniers et al., 2011).

Teaching examples

- Moot Court | SSC2024 | International Law

- Mini-internship | BMZ2023 | Kijken in de Zorg

- Improv theatre for character strengths | PSY3383 | Improv(e) your Soft Skills

- Collaborative online intercultural learning | PSY4126 | Virtual Collaboration for the Common Good

- Service learning | ECA | Maastricht Mediation Clinic

- Teaching learning activities | Empathy

- Honours+ | Faculty of Law

References

- Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2005). Liberal education outcomes: A preliminary report on student achievement in college. https://www.aacu.org/leap

- Davis, M. (1980) A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 10, 85.

- Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 113-126.

- Empathy. (2020). APA Dictionary of Psychology. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/empathy

- Powell, P.A. (2018). Individual differences in emotion regulation moderate the associations between empathy and affective distress. Motivation and Emotion, 42, 602-613.

- Reniers, R., Corcoran, R., Drake, R., Shryane, N., & Völlm, B. (2011). The QCAE: A Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(1). 84-95.

- Sala, A., Punie, Y., Garkov, V., & Cabrera, M. (2020). LifeComp: The European framework for personal, social and learning to learn key competence (No. JRC120911). Joint Research Centre (Seville site). (https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC120911)

Fairness

Impartial and just treatment or behaviour without favouritism or discrimination; not letting personal feelings bias decisions.