New technologies: Heroes or villains?

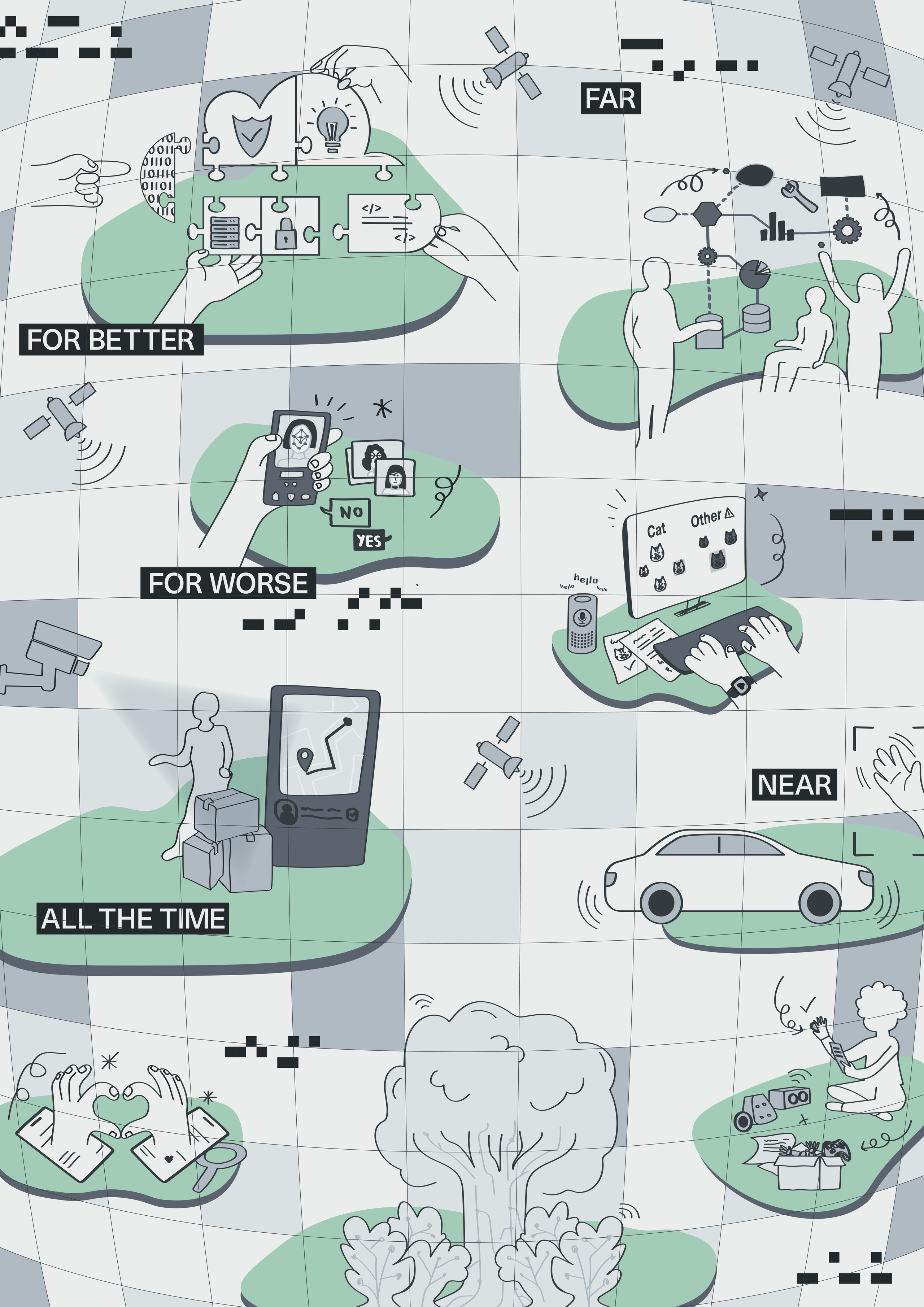

Hero or villain; utopian or dystopian; good or bad. If you think for a minute about what you see in the media today, when it comes to new technologies, the landscape is full of similarly opposing claims, from public figures and tech journalists, to CEOs and politicians; It is almost impossible to avoid the hype surrounding AI, self-driving cars, cryptocurrency, or virtual reality. But how do we avoid getting swept away in the hype, while at the same time avoiding becoming overly cynical?

Dani Shanley, Assistant Professor in Philosophy, tries to unpack how and why technology is often understood as a hero or a villain, and considers what it means to try and develop technology responsibly and how technological change may trigger us to re-evaluate what responsibility itself actually means.

More than box-ticking

According to Dani, “the concept of responsible innovation became popular between 2010 and 2020, particularly in funding and policy discussions. However, defining what it means to do research and innovation ‘responsibly’ remains a challenge, as many different factors shape its implementation. Responsible innovation is typically understood in different ways. For example, policymakers, such as those in the European Commission, typically focus on concrete frameworks – codes of conduct, diversity policies, and ethical compliance measures. These then serve as requirements which researchers are expected to follow. On the other hand, academics tend to adopt a broader, more philosophical perspective, questioning not just whether research meets ethical criteria but also how research agendas are set and whose voices are included.”

A key concern in the policy context, is that responsible innovation can become seen as a simple checklist, where researchers focus on meeting predefined criteria rather than engaging in meaningful ethical reflection. “Responsible practice goes beyond compliance; it requires ongoing dialogue and self-examination about the purpose and impact of what you are doing,” Dani claims. “Additionally, while public research institutions often integrate ethics into their projects, private companies operate with greater autonomy. Industry partnerships offer opportunities for ethical engagement, but they also present dilemmas. When companies fund research, how much freedom do researchers have to critique their practices? Can ethical concerns be raised without jeopardizing the funding?”

Who gets a say?

Dani regularly works alongside engineers and AI developers through her collaboration with colleagues at the Department of Advanced Computer Science (DACS) at the Faculty of Science and Engineering (FSE), as well as in her role at the Brightlands Institute for Smart Societies (BISS). Much of her work consists of trying to find ways to bridge disciplinary divides, integrating ethical reflection into technical workflows. “Many innovators genuinely want to create solutions that improve society, yet ethical considerations often come into play late in the process. Another major hurdle is that ethical reflection takes time, which can be perceived as slowing development processes down. Companies and researchers working under tight deadlines may resist pausing to consider broader implications. But it is easier to make changes to an innovation in the design-stage than in the implementation stage. Additionally, responsible innovation requires funding, and financial constraints can limit the extent to which ethical concerns are prioritised.”

Another challenge is ensuring that technological solutions actually meet the needs of those they are designed to serve. “Developers may envision solutions which are based on their own assumptions, but without engaging affected communities, their innovations may miss the mark. Engineers need to think carefully about how the problem they want to solve is being defined – and by whom. What is the positive change they think they will achieve by developing a particular technology? Who is actually affected by the problem at hand? Have they been included in the problem definition? Can they also be included in other stages of the development process? Success in innovation should not be measured solely by what is technically possible, but also what is societally desirable,” Dani emphasises.

Real-world harm

Technological advancements are often accompanied by hype, with grand promises about how innovations will transform society. But, “while optimism can drive progress, it can also lead to unrealistic expectations and misinformation,” Dani claims. “Generative AI, for example, has been hailed as a revolutionary tool, yet its real-world consequences – in terms of environmental impact, bias and misinformation, labour exploitation, and copyright infringement – are huge.”

“AI’s incursion into warfare has not only mechanized destruction but has also distanced those responsible from its consequences. Nowhere is this clearer than in the use of Israel’s Lavender programme, an AI-powered system that designates targets in Gaza with chilling automation. Touted as an efficiency tool, Lavender flagged tens of thousands of Palestinians as threats, often based on opaque criteria and faulty data. Rather than reducing collateral damage, it has enabled a staggering rate of civilian casualties – turning intelligence gathering into a numbers game where errors cost lives. The illusion of algorithmic precision makes these killings feel sanitized, even justified, while accountability dissolves into machine logic. AI doesn’t bring moral clarity to war; it obscures it, making slaughter scalable and responsibility diffuse.”

“AI-driven healthcare tools are another example. These tools are often framed as solutions to systemic failures, but they can just as easily deepen them. Consider a robot designed to perform breast exams – a prototype of which I actually saw in a lab I visited last year. According to its designers, the robot is being developed to help address workforce shortages. But what is lost when a mechanical arm replaces a nurse, reducing an intimate, anxiety-ridden experience to the cold precision of automation? A nurse does more than palpate tissue; they read body language, offer reassurance, and respond to unspoken fears. The push to automate medicine under the guise of efficiency erodes these nuances, treating care as just another task to optimize. The problem isn’t just that robots are performing exams – it’s that, in the process, we risk redesigning healthcare to accommodate the machines rather than the patients.”

These examples illustrate how promises about the future often hide the real world harms we risk exacerbating by prioritizing technical solutions to societal problems. “Deciding whether to use these tools, and in what way, is a responsibility that we all have to consider now. We need to critically interrogate the tools we use in a world where the regulation has not yet caught up with the technology. We have to ask ourselves, what kind of world do we want to be a part of?”

The right to resist

Another important question is whether and in how far society has the right to resist certain technologies. Too often, technological advancements are presented as inevitable, but should they be? If a technology reinforces discrimination, invades privacy, or erodes human interaction, shouldn’t we have the right to refuse it?

According to Dani, “throughout history, resistance and activism have played a crucial role in shaping technological developments, often redirecting them away from exploitative or oppressive uses toward more equitable applications. In recent years, activists, scholars, and technologists have exposed the racial and gender biases embedded in AI systems – such as facial recognition disproportionately misidentifying people of colour – leading to stricter regulation and even outright bans on the use of the technology in certain domains. Recognising that innovation is not a one-way street can help to empower individuals and communities to shape technological progress in ways that align with societal values. We need to ensure that technologies are developed to serve humanity and not the other way around.”

Educational initiatives can also play a role in fostering ethical awareness. By integrating ethics into engineering and data science curricula, together with our DACS colleagues, we are trying to prepare future innovators to recognize the importance of responsible research from the outset. Rather than treating ethics as an afterthought, we are trying to ensure that it is woven into the fabric of technological development.”

Text by: Eva Durlinger

Pictures by: Claire Gilissen and Joudi Bourghli

Also read

-

Four FASoS researchers awarded NWO XS grants

How do lobbyists use disinformation to sway policymakers? Who gets to shape the historical narrative of occupation and violence? Does growing inequality change the way citizens think about politics? And how have politicians defended “truth” across a century of media revolutions?

-

Christian Ernsten awarded funding for project on recurating colonial-era collections

UnRest focuses on the historically significant yet deeply contested archives and artworks associated with Robert Jacob Gordon (1743–1795) – a Dutch military officer and explorer whose documentation of the Cape region shaped European knowledge of South Africa during the 18th century

-

Massimiliano Simons awarded funding for innovative art–science project on hybrid plants

"Entangled Genes: Sharpening the Public Debate on Hybrid Plants” is a new artistic research project that aims to deepen societal reflection on genetically modified plants.