Innovation, AI, and Smallholder Farming: Insights from My FSD Internship

As part of my research internship at the Fair & Smart Data (FSD) project, I’ve been balancing thesis work, communication tasks, and gaining a closer look at how academic research functions in practice. In this blog, I will share some reflections from this experience, particularly my take on innovation and AI in the context of smallholder farming.

Expectations vs Reality in Academia

At the start, I had a somewhat idealised view of academic life. I pictured a world of uninterrupted thinking, ambitious plans, and occasional unpredictable results. In reality, it’s far more nuanced and, like any job, it has its ups and downs.

Most of my tasks at FSD were focused on social media and content creation, such as posters and graphs. Working with FSD’s experienced researchers gave me the opportunity to observe how academic research actually unfolds. I learned that the aim isn’t just to produce knowledge, it’s about navigating uncertainty, working across different perspectives, and learning to ask more precise and meaningful questions.

This often comes in combination with other responsibilities, which can make the process appear somewhat chaotic from the outside. Think: multiple research meetings a day, collaborations that leave you on read, and brilliant ideas that stall due to funding gaps. While this might sound unappealing at first, it helped me understand how knowledge is actually built: slowly, socially, and with a lot of trial and error.

It also made me reflect on the value of the process itself. While results are important, especially when it comes to communicating impact, for the researcher, the process carries just as much weight. There is always more to explore, adjust, and refine.

What I learned at FSD

This experience encouraged me to share ideas earlier, to welcome feedback, and to see change not as a disruption, but as a natural part of the work. Remaining curious was essential, particularly when engaging with subjects I was previously unfamiliar with, such as smallholder farming.

Over time, I became more familiar with smallholder conditions, trade dynamics, and the challenges they face, both through personal research and through creating content for LinkedIn, reviewing internal documents, and formatting presentations. Specifically, I got to explore areas like smallholder conditions, digitalisation, and fair value chains. I also worked on communication for webinars and helped break down internal research on topics like the voluntary carbon market or the development of digital IDs for farmers. This new knowledge not only broadened my understanding of agricultural systems but also connected the dots between field-level challenges and high-level policy conversations, giving insight into bigger industry dynamics, and relating to concepts learned through my business engineering degree.

AI and Smallholder Farming: Insights from My Thesis

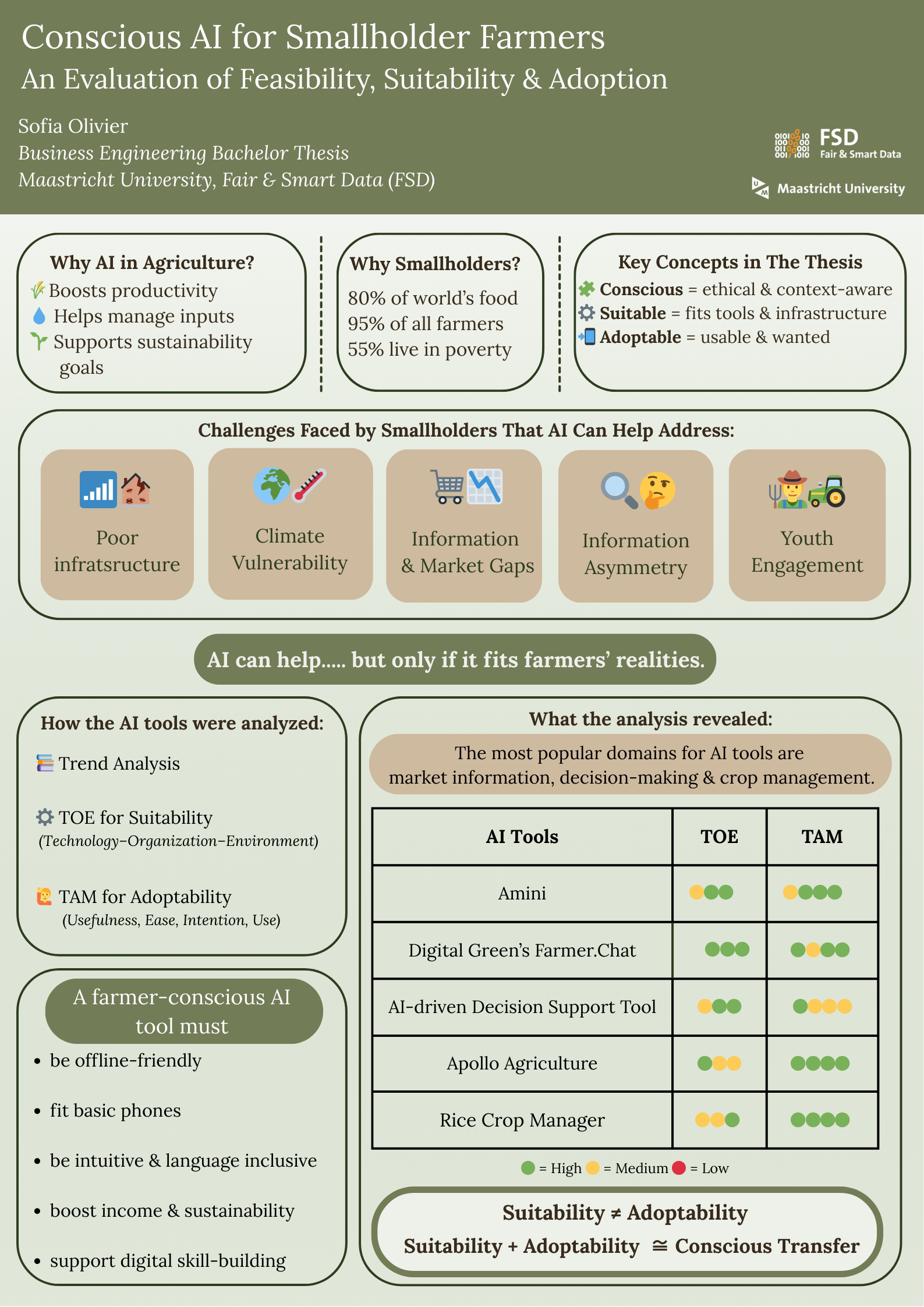

In parallel, I completed my thesis on the role of AI in smallholder farming, specifically looking at how these innovations are being transferred to smallholders, and whether that process is conscious and context-aware. I wanted to understand whether the technologies being introduced are truly suitable and adoptable from a smallholder perspective.

To do this, I conducted a literature-based analysis, starting with a trend review of how AI is currently applied in agriculture. Then, I evaluated the findings through two lenses: the Technology-Organisation-Environment framework to assess suitability, and the Technology Acceptance Model to explore adoptability and perceived usefulness.

From this analysis, I developed a set of recommendations outlining the key characteristics AI tools should have to ensure they are transferred in ways that are both ethical and aligned with smallholders' needs and realities.

What stood out most to me was how much adoption depends not just on what a tool does, but on who it is designed for. Even the most advanced systems don’t work if they overlook issues like connectivity, language, or the actual ability of farmers to interact with the tool in a meaningful way. At the same time, there are success stories, cases where relatively simple solutions are making a tangible difference on the ground.

Over the past few months, I’ve gained enough insight to form a personal perspective on the transfer of innovation, one that is by no means absolute or definitive, but grounded in what I’ve observed and studied. I believe that innovation can be successfully transferred to less compatible contexts, but only if the process is facilitated, supervised, and shaped by the needs of those expected to implement it. Without this, even well-intentioned innovations risk creating long-term harm or becoming unsustainable for the people they’re meant to support.

In the context of AI and smallholder farming, this holds especially true, and it’s one of the reasons I chose to focus my thesis on this topic. My findings largely confirmed this initial assumption: yes, innovation can bring positive change, but it can also introduce new difficulties or deepen existing inequalities if not applied thoughtfully. The transfer must be guided, and a feedback loop must be in place to ensure that adoption is fair, context-sensitive, and responsive over time.

Final Thoughts

Looking at AI tools with a critical lens, while also being embedded in a research environment like FSD, gave me a more grounded understanding of what “innovation” really means. It’s not just about what’s new or cutting-edge; it’s about what fits into people’s lives, systems, and challenges in a thoughtful and useful way.

This internship gave me the chance to see how research and innovation interact, not just in theory, but in practice. It showed me that meaningful innovation doesn’t start with technology, but with understanding people, contexts, and the systems they navigate every day.

Also read

-

Assessment is beautiful

While the Dutch word for assessment (toetsen) often carries a negative connotation, Desirée Joosten-ten Brinke sees it as something quite beautiful.

-

Five Veni grants for FHML researchers

Within FHML, five researchers are awarded a Veni grant of up to 320,000 euros to further develop their research ideas.

-

“Anyone can shout from the sidelines”

Sjoerd Maillé holds a bachelor’s in Law and a master’s in Law & Labour (cum laude) from Maastricht University. Born and raised in Brabant, he now works as a trainee at the Limburg District Court. At just 24 years old, he is also the second youngest member of the Limburg Provincial Council and a...