AMIBM: University collaboration at Brightlands

Eighty years ago, DSM opened its central laboratory for fundamental research in Geleen. Now the old lab is part of the Brightlands Chemelot Campus, a place where more than 3,900 researchers, entrepreneurs and students work on new sustainable materials. This coming fall, the Festival Feel the Chemistry will look back on eighty years of innovation and will also look ahead to the future. Maastricht University is one of the founders of the campus and is closely involved in the developments. It’s at the heart of the campus, as is the Maastricht Institute for Biobased Materials.

Almost five years ago, the universities of Aachen (RWTH) and Maastricht (UM) founded the Maastricht Institute for Biobased Materials. This made AMIBM the first cross-border research institute in the field of new biological materials.

Richard Ramakers sighs. He has just wrapped up a gruelling interview. “We’re in the middle of an in-depth evaluation”, explains the managing director of AMIBM in his office at the main building of the research campus, overlooking CHILL labs where students and researchers are working in white coats. “At the start in 2016, a lot of money was put on the table for this institute by the universities and the province. We set up the labs, hired people and built a network with the other research institutes here on campus and in Germany. Of course, we have to justify what we’re doing here and what the output is. But we do so much here. It’s hard to keep track of which projects are currently being worked on here; how many students, teachers and researchers come here every day; what the spin-offs are; the further plans. For example, I was asked how many companies we have (had) contact with. Well, more than 100. It’s all down on paper, but it's a lot of work to get everything into a clear overview.”

Performance

It’s a lot of work, but the managing director's sigh also indicates that things are going well at AMIBM. Last spring, the Province of Limburg extended the follow-up grant for another four years. “Because we’re performing above expectations. There are now 100 people working here—more than double what we initially estimated. The number of scientific publications is higher than expected, there are several spin-off companies and the UM master’s programme in Biobased Materials attracts students from all over the world. AMIBM has put itself on the map at record speed. We’re proud of that, of course. Ultimately, we’ll be self-supporting as a research institute and running without a provincial Kennis-As grant.”

Spearheads

AMIBM was set up to develop new materials for industry and medical applications based on biological raw materials, one of the spearheads of the Brightlands Chemelot Campus. “The starting point was the combination of the best of different worlds”, declares Richard Ramakers, referring to the collaboration between the universities of Aachen and Maastricht, together with the renowned German institute Fraunhofer. “That’s not a simple thing. Basic chemistry and medical science are coming together here. These are actually two different worlds in which different languages are spoken—those of polymers and production, of fundamental research and micrograms. This is evident on a daily basis, but we’re increasingly succeeding in bringing together this enormous concentration of knowledge, skills and facilities within a radius of about twenty kilometres. With tangible results, which are visible in various concrete innovations. We’re actually only at the beginning stages.”

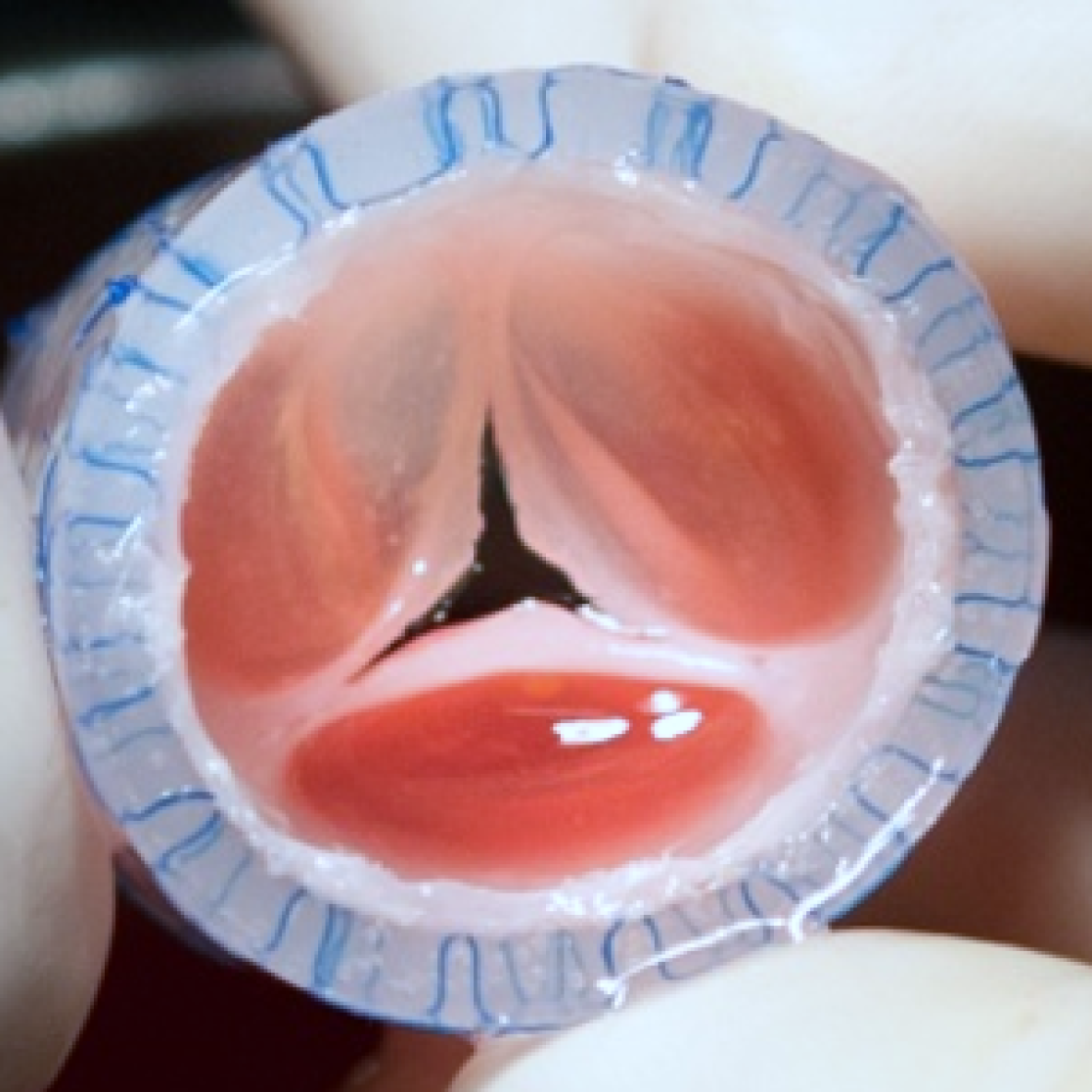

Elastin in heart valves

It’s not easy to choose from the dozens of projects AMIBM has already completed or is working on. Stefan Jockenhövel, co-founder of the institute and now scientific director, chooses the search for the substance elastin. It’s intended for use in a new generation of heart valves. “The future is the cultured heart valve that grows with the heart”, explains the former heart surgeon, who has been fully committed to the development of a better heart valve for years now. “This is essential, for example, for children who need a replacement heart valve. They sometimes need to be operated on as many as eight times. A cultured heart valve that grows with the patient is possible, but for now this type of valve is still too stiff because the elastin is missing. The human body produces its own elastin so that the heart valve remains flexible, which is necessary for it to function properly. This type of valve gets worked pretty hard—continuous movement, resisting the pressure of the blood. Flexibility is crucial. Here at AMIBM, we’ve managed to recreate this substance. And tests also show that it can be incorporated into the cultured valve. The next step is further research in the labs, followed by animal testing and finally clinical trials. It’s a promising development, yes, partly conceived here on campus.”

Chitosan to fight bacteria

Richard Ramakers has another nice example: Chitosan. “Or, rather, a new kind of Chitosan”, he explains. “Chitosan is a substance with strong antibacterial and antifungal properties. It’s used in plasters, bandages and in protective layers of plant seeds. It’s a super substance that is extracted from the exoskeletons of insects and crustaceans. This is currently done using a rather intensive chemical process. We’ve found a special bacterium in the North Sea that can digest the shells of shrimp. And guess what? If we combine the right enzymes of this bacterium, we can produce a perfect kind of Chitosan in no time—good and efficient. And widely applicable, it’s expected, for example, as coatings for implants and prosthetics so that they will no longer become infected or be rejected. But that’s still a long way off. However, we’re now working on an earlier application for improving face masks—quite relevant in the time of corona.”

Close ties to practice

Michelle Gian chose the two-year Master's programme in Biobased Materials at Maastricht University after her studies at Fontys University of Applied Sciences in Eindhoven. “Because sustainability plays a major role in this master's programme”, she says, “and because it’s closely tied to professional practice nearby. The labs, the pilot plants, the chemical industry are just around the corner. On the Brightlands Chemelot Campus, we work directly with entrepreneurs and researchers. You get to know people very quickly, get to look behind the curtains at companies, and there’s room for your own ideas. Together with other students, for example, I made an antibacterial coating from lemon peel, which can be used in bandages or plaster casts. We also extracted keratin from sheep’s wool and processed it into a gel that can extract CO2 from the air. These kinds of projects are the order of the day at the AMIBM labs.”

In October, 23-year-old Gian will start her final thesis. “Here on campus, we will investigate whether elephant grass is suitable as a raw material for biobased materials. And after that? Maybe a PhD or a job in this field. As long as it has to do with sustainability.”

Also read

-

Machines that can improvise

Computers are already capable of making independent decisions in familiar situations. But can they also apply knowledge to new facts? Mark Winands, the new professor of Machine Reasoning at the Department of Advanced Computing Sciences, develops computer programs that behave as rational agents.

-

A second chance for plastic

If we were to replace plastic with paper or glass, would the environment benefit? Surprisingly, no, says professor of Circular Plastics Kim Ragaert. She is calling for an alternative approach aimed at increasing awareness of and knowledge about recycling.