‘Let's remember people for who they were’

We often know no more about war victims than their date of death and the way they died. Amanda Kluveld, associate professor at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, is committed to discovering more. She gives a face to victims of war, particularly the Second World War. In archives, she recently came across a number of extraordinary letters dating from this period.

In March 1941, Helene Schickler, a German-Jewish widow, went into hiding in a convent in Naples. Her plan was to flee further, via Lisbon to family in the United States, but the Portuguese authorities refused to allow her through. In desperation, Schickler wrote a letter to her son in Boston. A week later, none other than Harpo Marx, one of the famous Marx Brothers, suddenly made an appeal to Bert Fish, the Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiar to Portugal. In his letter, Marx asked Fish to help his ‘aunt’.

Time to dig deeper

It was Amanda Kluveld who discovered this letter from Marx in the archives of the US embassy in Lisbon. It was a matter of pure chance. ‘I wanted to know more about the story behind a photograph taken in Amersfoort in the summer of 1943,’ Kluveld says. ‘For a long time it had not been clear who and what the photo shows, and no historian had paid it any attention. I had already discovered that I might find more information through the US embassy in Madrid. But since Lisbon was important for escape routes to America during the Second World War, and it was relatively nearby, I decided to search the embassy archives there as well.’ (text continues below italicised text and picture)

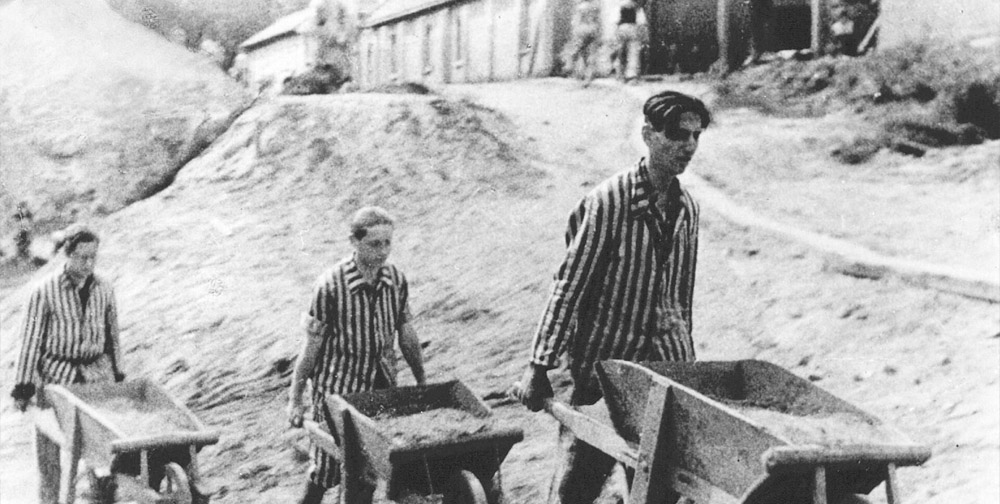

The ‘Amersfoort photograph’

The photograph that led Kluveld to search the archives of the embassy in Madrid takes us to the heart of Amersfoort during the Second World War. In the summer of 1943, 70 Jewish men, prisoners from the Vught concentration camp, were ordered by the occupying forces to dig out a shooting range in the grounds of a barracks. Locals could see that the men were being mistreated by the SS and Wehrmacht guards. They tried to help the prisoners, but were driven away, threatened and even shot at.

12,000 record cards

For several years now, Kluveld and her fellow historian Jan Weitkamp have been delving into personal stories behind the Second World War, in order to give a face to the victims. ‘You often start with a number, name or place, and continue from there,’ Kluveld says. ‘With some detective work, there’s always information you can find – sometimes from letters, such as those of Harpo Marx, but usually from other sources, such as texts in foreign languages and endless lists of names. For the photo from Amersfoort, we went through 12,000 record cards from a concentration camp.’ (text continues below italicised text and picture)

Plea from a film producer

One of the other letters Amanda recently found was from the late American film producer Sol Lesser. He also wrote to Fish, the US ambassador to Portugal, asking if Fish would help a ‘cousin of his mother-in-law’ to reach America. Unfortunately, Fish turned down his request. The ‘cousin’ – in reality probably a friend of the family – was deported to Auschwitz and murdered.

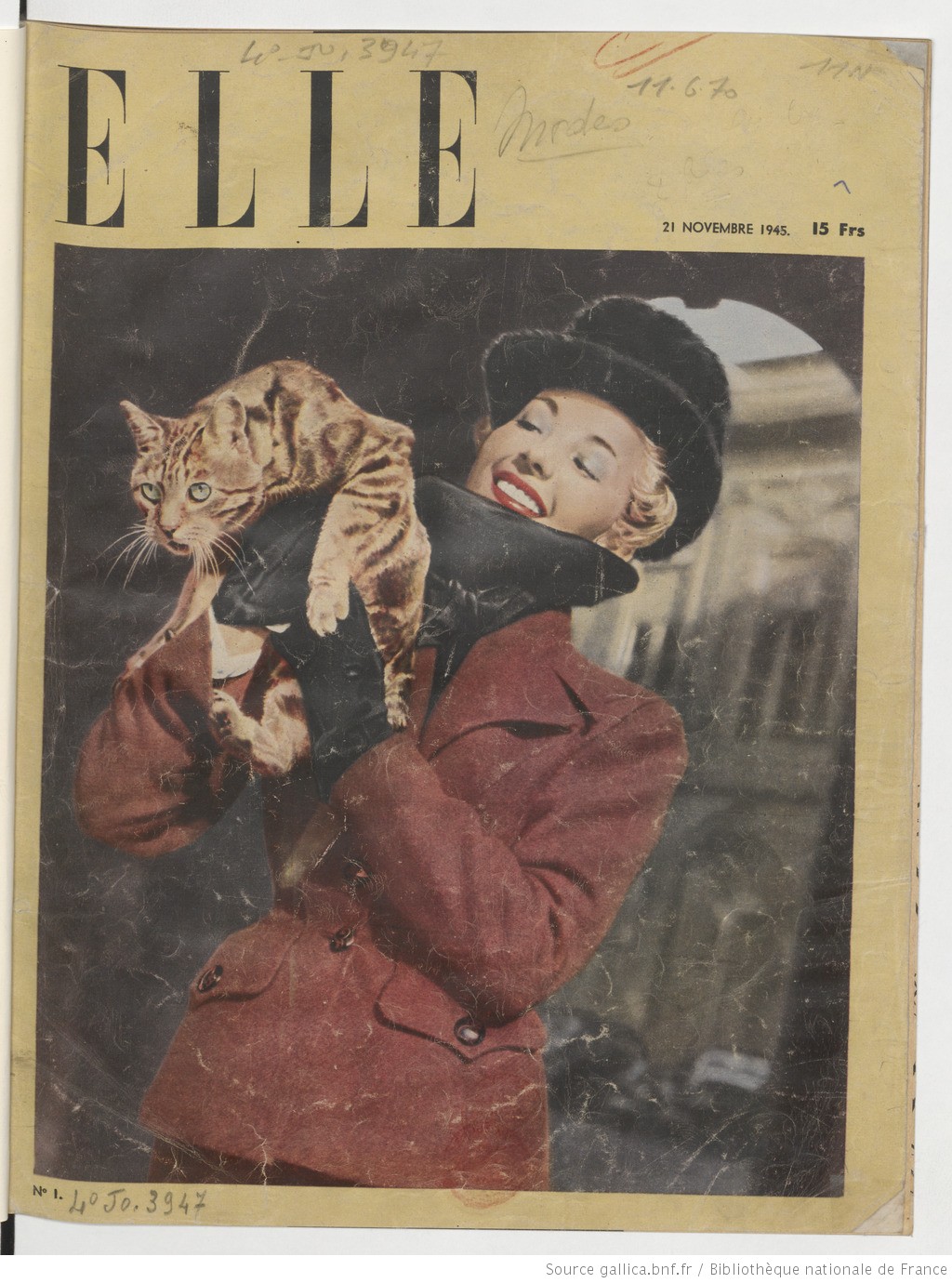

The founder of ELLE

Another famous person from whom Amanda found a letter is the Republican presidential candidate and challenger to Roosevelt, Wendell Willkie. In 1940 he requested free passage through Spain for the parents of the editor of the women’s page of The New York Times , the Russian-Jewish journalist Hélène Gordon-Lazareff, who fled to America during the war. With Willkie’s help, her parents eventually also made it to the US. Helene herself returned to liberated France in 1944, where she founded the fashion magazine ELLE.

Murder in the Amersfoort concentration camp

A good example of justice is the story of Ida Johnson, an African American woman imprisoned in the Amersfoort concentration camp during the Second World War. While she was there, a Jewish prisoner was murdered. Later, in transit from England to the US, Ida made a statement to the US authorities describing the atrocities committed against Jews in the Amersfoort camp. Her statement was taken seriously because she was not Jewish herself. Thanks to her testimony, a statement by a fellow Jewish prisoner from the Liebenau internment camp was also believed. Amanda is seeking recognition for Ida and her actions.

The fate of Schickler

Kluveld has plenty of new research topics left to tackle. ‘I’m still studying the 70 prisoners in Amersfoort, about whom I’m writing a book with Jan Weitkamp. For another project I’m working on the identification of all Jews who were imprisoned in the Amersfoort concentration camp. I’m also carrying out new research on a German family who fled to the Netherlands during the war. One family member went into hiding, another ended up in Riga. Little attention has been paid to their story.’

Does Kluveld know what happened to Helene Schickler? Did Harpo Marx’s letter have any effect? Sadly, it didn’t. As in the case of Sol Lesser, Kluveld found a letter turning down the request. Helene probably died in Auschwitz, a conclusion endorsed by one of her relatives by marriage, with whom Kluveld had contact. What is certain is that Helene was not Marx’s aunt, but his aunt’s sister-in-law. Marx’s letter was eventually to end up in the online archive of the Lisbon embassy. The rest is history.

For more information about Amanda and her research, go to: www.oorlogservaringen.nl.

A scoop

Amanda Kluveld and Jan Weitkamp made another special discovery concerning Ida Johnson: they have been able to make it plausible that Ida Johnson and her two daughters were witnesses to the mistreatment of Salomon (Monne) Rodrigues de Miranda, former alderman of Amsterdam. This mistreatment would eventually lead to his death.