Özge Gökdemir and Devrim Dumludağ reveal differences in competitive behaviour between women in the Netherlands

Economists and spouses Dr Özge Gökdemir and Professor Devrim Dumludağ conducted a study for Maastricht University that reveals differences in competitive behaviour between women in the Netherlands. Their findings will be published soon in a scholarly journal. Here, they give us a sneak peek.

Gökdemir and Dumludağ spent three years working on a research project where they have been studying the competitive behaviours of women, men, and migrants. One of their themes is titled ‘Do All Women Shy Away from Competition? Competitive Preferences Among Dutch and Non-Western Females in the Netherlands.’ The data for this research come from the LISS (Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences) panel, which forms a representative slice of Dutch society, covering roughly 5000 households from all over the Netherlands. Participants fill in questions online and their responses are used as data in a range of academic studies.

Behavioural analysis

“We analysed the data from two existing studies. These data came from questionnaires and online experiments,” Gökdemir says. “We compared the behaviour of native Dutch women with that of non-Western immigrant women. Our analysis showed that Dutch women tend to be less competitive than first-generation non-Western immigrant women. And competitiveness is notably higher among non-Western women from countries characterised by gender inequality.”

Dumludağ offers a possible explanation. “These women had to be competitive to survive in their country of origin. They only had themselves to fall back on; they couldn’t count on support from the government. When they emigrated to the Netherlands, they brought that attitude with them.”

The results also showed that second-generation non-Western migrant women are much less competitive than their mothers. “These women seem to have adopted the prevailing norms and values of Dutch culture. They were born and raised in the Netherlands and never had to fight for their existence. As a result, their behaviour is less competitive and more like that of native Dutch women. Which is a pity, because they have a lot of potential.”

Male breadwinner

Gökdemir and Dumludağ’s results support findings by other researchers showing that Dutch women are less competitive than Dutch men. “It’s not that Dutch women lack ability, but they’re less willing to compete with others,” Gökdemir says. “This can partly be explained by Dutch culture. For many Dutch people, it’s still the norm for the man to be the breadwinner. The woman usually takes care of the children and works part time. If women start working more, they’ll have to pay for their children to go to daycare. They’ll also pay more tax while losing their eligibility for benefits. And if working full time doesn’t pay off, why would you do it?”

Devrim Dumludağ is a professor at the Department of Economics at Marmara University, Istanbul. He obtained his PhD at Boğaziçi University in 2007. He was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Groningen in 2008, a visiting fellow at Erasmus University Rotterdam in 2009 and a visiting fellow at Maastricht University from 2012 to 2014. His research focuses on economic development and institutions, subjective wellbeing and the relative income hypothesis, behavioural economics and happiness economics.

Cheaper childcare

The government can play a key role in breaking this pattern, the researchers say. “In the current situation, working more doesn’t make them better off,” Gökdemir says. “That could be improved by making childcare cheaper and reducing taxes for couples who work full time. Or by offering more annual leave, which makes it easier for parents to take time off when their child is sick.”

That’s not all. “Schools could also teach young people about gender equality and raise awareness that your abilities are independent of your gender. And the government could help women identify their abilities and make better use of them,” Dumludağ says. “Of course,” Gökdemir adds, “we don’t want to force anyone to work full time. But if women are able and willing to work, it’s a shame if they’re hindered in their aspirations by societal expectations and systems. That leads to a huge pool of untapped potential at a time when the labour market is facing major shortages.”

If women are able and willing to work, it’s a shame if they’re hindered in their aspirations by societal expectations and systems.

Özge GökdemirSecond home

Gökdemir and Dumludağ enjoyed conducting research as a couple. The opportunity does not come around often: in Turkey, they teach at different universities. They have since returned to Istanbul, but visit the Netherlands regularly for a follow-up study on competitive behaviour in children. “We really enjoyed our time in Maastricht,” says Dumludağ. “The university has a good atmosphere and pays attention to its employees’ health and wellbeing. The Netherlands and Maastricht now feel a bit like our second home.”

Text: Martina Langeveld

Also read

-

SBE researchers involved in NWO research on the role of the pension sector in the sustainability transition

SBE professors Lisa Brüggen and Rob Bauer are part of a national, NWO-funded initiative exploring how Dutch pension funds can accelerate the transition to a sustainable society. The €750,000 project aims to align pension investments with participants’ sustainability preferences and practical legal...

-

Fresh air

Newly appointed professor Judith Sluimer (CARIM) talks about oxygen in heart functioning and the 'fresh air' the academic world needs.

-

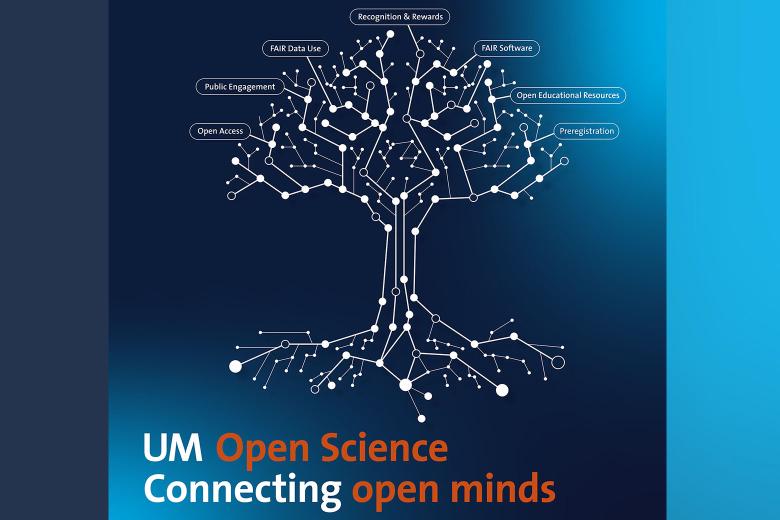

What exactly is Open Science?

Open Science proposes openness about data, sources and methodology to make research more efficient and sustainable as well as bringing science into the public. UM has a thriving Open Science community. Dennie Hebels and Rianne Fijten talk about progress, the Open Science Festival and what...