Bye bye culture – enter norms and codes?

Fond of regulations as they are, jurists could nonetheless have an interest in learning about their origins and current proliferation, and Olivier Roy’s latest book addresses this question by offering a thought-provoking reflection about the path that contemporary culture has taken.

Joyful news 🥳

Did you check out last March’s QS World University Rankings 2025…? 😳 Maastricht University Faculty of Law was ranked 65th globally, and even the highest of all law schools below 50 years of age. 😊 😎 It’s great, and a boost for our community of staff and students. At least our beloved former Minister of Education Eppo Bruins didn’t succeed in cutting down that achievement! 😉😂

The paragraph above contains two recent, seemingly unconnected cultural mutations that are discussed in The Crisis of Culture. Identity Politics and the Empire of Norms (the original French title from 2022 is the more telling L’aplatissement du monde, “The Flattening of the World”), the latest book by the French political scientist Olivier Roy (b. 1949). There is the ranking of colleges and universities throughout the world, first introduced by the “Shanghai Ranking” in 2003, and the role of emojis in our written language use. What is characteristic in the rankings is the defining of a sort of excellence that is totally removed from local cultures, for a precise cultural reference would only hinder a global comparison. As of emojis, they represent a finite number of differentiated elements that offer a spectrum from ready-to-cry to ready-to-laugh emotions, leaving as little room as possible for ambiguity, and are - in principle - understandable for all.

What is common to and relevant about these phenomena, according to Roy, is that they reveal a crisis of culture. The book starts from a number of unavoidable current issues: feminism, the crisis of masculinity, intersectionality, gender versus biological sex, identity versus universalism, cultural appropriation, “wokeism”, cancel culture, the purging of artworks and literary classics, not to mention immigration. Central to all of them is the issue of culture. Interestingly, however, Roy does not take a progressive or conservative stance in these discussions, nor does he diagnose them as a clash of values or “civilisations”. Instead, his book seeks to analyse the relationship between culture and norms, with a clear thesis: we are not in the midst of a cultural transition but a crisis over the very notion of culture, the chief symptom of which is the extension of normative systems. Additionally, Roy argues that the transformations of “cultures” into explicit coded systems destroys the notion of culture itself. The opening chapter of the book takes as its point of departure four radical developments that have changed the world since the 1960s: 1) the transformation of values with the individualist and hedonist revolution of the 1960s; 2) the internet revolution; 3) neoliberal financial globalisation; 4) the globalisation of space and the movement of human beings - in other words, deterritorialisation.

Two concepts of culture

Among the many meanings of “culture”, Roy distinguishes two poles: culture in the anthropological sense, as a common framework of meaning and representations specific to a given society or community, and culture as canon (or high culture), which indicates a set of intellectual and artistic productions selected and considered “good” to know or to practice. The former is implicit, the latter explicit.

Central to Roy’s analysis is the notion of deculturation – which already played a central role in his earlier books Globalized Islam and Holy Ignorance. Deculturation designates the process of cultural dilution, which is well visible in dominated groups like immigrants, whose culture experiences a crisis as early as the second generation, and is usually followed by “acculturation” - the blending into a dominant culture. Against this background, Roy observes that today supposedly all categories of the population feel culturally insecure, even when not “dominated”, but there is no common culture on the horizon. As a result, many political and social movements appear as forms of social separatism of likeminded people: see, for example, The Benedict Option (for Christians living in an increasingly secular world) and the Occupy movement. In short, there is no lack of subcultures, but they miss the sociological grounding to be real social movements.

On another level, high culture is in crisis as well. We need not look far: universities – claiming to be universal yet, at least since the nineteenth century, linked to a national framework – are the place where high culture is defined and perpetuated. Several developments have however called into question such transmission. Both neoliberalism and cultural and postcolonial studies see the canon as an imposture. According to the former, the canon, together with the notion of a person’s moral and intellectual training, serve no purpose. The latter claims that high culture alienates and excludes rather than liberates. In this sense, the neoliberal quest for “excellence” generally leads to quantitative measurement becoming central everywhere. This is fundamentally at odds with high culture as such, which remains deeply rooted in a national, cultural and linguistic framework and is hardly quantifiable.

Flamboyant menus, our European way of life, and sequenced sexuality

Roy examines this mutation in various domains. Time and again, it is the “deculturation of cultures” that renders explicit things, signs and phenomena that used to be implicit – as a self-evident component of a broader cultural context. Among many examples, often hilarious, there is cuisine, as menus have experienced an inflation in adjectives that describe taste rather than food. Asked to choose between perfectly identical plates with a different name – “An oven-roasted, stuffed, boneless, skinless chicken breast. Served with wild rice and vegetables” or “Citrus marinated chicken breast stuffed under the skin with shrimp and crabmeat, grilled over a hickory fire, then served with a sweet and spicy Georgia peach sauce, saffron wild rice, and fresh vegetables” – customers chose the latter, even though it was more expensive.

Take the EU’s cultural identity: in the absence of a consensus, in 2019 the Commission decided to appoint a commissioner in charge of “promoting our European way of life”. This was clearly created to handle immigration, but the identity upheld turned out to be reactive and shallow, only drawing on the smallest common denominator of everyday life, without any ideas on culture. Revealingly, Roy quotes from a random similar attempt, the “Starter Kit” for families migrating to the Belgian region of Flanders (2012): “Flemish people like peace and quiet. No noise is permitted after 10 pm […] The Flemish eat chicken, fish, beef and pork. Some people are vegetarians. The Flemish also eat fruit and vegetables, potatoes, pasta and rice.” …

The mutation is not only about the implicit surrendering to the explicit, it is also about the expansion of normativity. Both tendencies are visible in the domain of sexuality. Increasingly since the 1960s, sexuality has become autonomous from culture. This has brought about the liberation of sexual desire, but also the diluting and distrust of its cultural coding (see the ongoing #MeToo movement). Consequently, a more unambiguous, normative system is required, reflected in the growing attention on “consent”. Since this notion is hard to define, sexuality is increasingly regarded as a series of specific acts, in which every sequence can be accepted or refused. According to Roy, this ultimately amounts to renouncing the experience of sexuality as an undivided whole, in which dark and light are inextricably linked. Roy: “I am not saying this is either progress or an aberration; I simply see this […] as expressing the logical consequence of the recoding of human practices, following the disappearance of cultural self-evidence and thus of implicitly shared understandings.”

Grassroots movements?

In a surprisingly summary conclusion, Roy points to the stalemate produced by the trilogy of deculturation, coding and normativity, which creates no new culture. But where does his analysis leave the reader and the world then…? The “ways out” offered by Roy seem foremost negative: the logic of like-minded “peers” – including that of Academe– is destructive; instead, “we must leave our protected spaces behind and rediscover heterogeneity, difference, and debate.” In a podcast interview about his book, Roy underlines the importance of real, offline social relations and grassroots life. Yet the only example he puts forward is the French Yellow vest movement, which was politically insignificant (and deliberately so). It is a modest harvest after a thought-provoking book about the path that culture – or rather its fragmentation – has taken. 👏 🤷♂️

P.C.L. van de Wiel

Pol van de Wiel is a Teacher at the department of Foundations of Law. He studied law (BA, 2011) and philosophy at Leiden University, history and political science at the Institut d'études politiques de Paris and political theory at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales in Paris (MA, 2013).

-

White Walkers, Red Lines: The IHL Case Against the Night King

Fictional battles have long served as a mirror for real-world anxieties about war, technology, and the limits of law. Season 8, Episode 3 of Game of Thrones, “The Long Night,” provides an opportunity to test the boundaries of international humanitarian law (IHL) by confronting its most fundamental...

-

A Fan’s Guide to Football’s Lex Sportiva: How the CJEU is Changing the Game

On April 28th, I published my very first podcast, which dived into the iconic field of Sports Law. This work was the product of an “Honours Programme Personal Project” supervised by Dr. William Bull. As I look back on this experience, I am honored to share some of the takeaways which Dr. Bull and I...

-

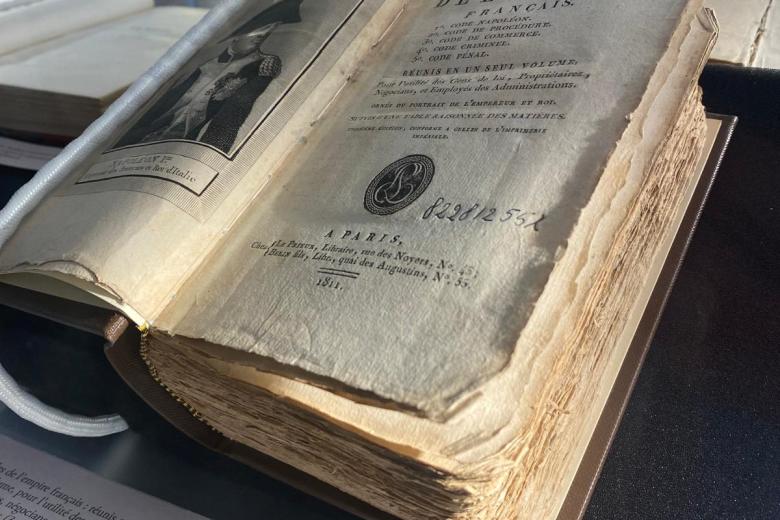

Object- and Problem-Based Learning (OBL & PBL): A Fruitful Amalgamation for the Development of Legal Education

Patrons at the Arthur W. Diamond Law Library at Columbia University (USA) can encounter a duplicate of an automobile wheel that relates to the 1916 court case heard by Judge Benjamin Cardozo in MacPherson v. Buick Motor Co. The wheel is an object that hangs on a wall on the fourth floor of the...