App stores as public utilities?

Representing the prototype of multi-sided platforms, app stores are at the forefront of the debate on digital markets. Several regulatory proposals place on app stores neutrality obligations vis-à-vis third parties. Are EU and US competition laws utterly unfit to tackle platform-related behaviours? What happens if we give up on economically-sound antitrust assessments?

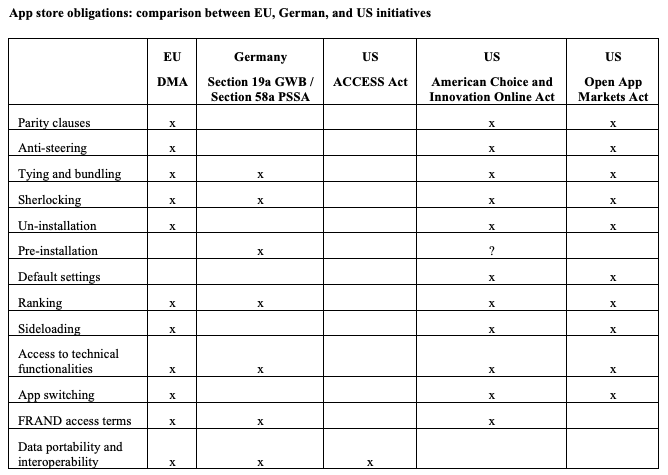

The gatekeeping position of Apple and Google and the related concerns about their rule-setting and dual role have been the subject of market studies launched by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), the Netherlands Authority for Consumers & Markets (ACM), the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), the Japan Federal Trade Commission (JFTC), and the U.S. House of Representatives. Furthermore, the terms and conditions for accessing app stores, such as in-app purchasing rules, restrictions on the freedom of choice regarding payment apps on smartphones, and near field communication (NFC) limitations are being scrutinised by courts and antitrust authorities all around the world. Finally, legislative initiatives envisage obligations explicitly addressed to app stores. Notably, the European Digital Markets Act (DMA) and some of the U.S. bills (i.e. the American Choice and Innovation Online Act, the Augmenting Compatibility and Competition by Enabling Service Switching Act, and the Ending Platform Monopolies Act) prohibit, for instance, the designated platforms from: discriminating between users by engaging in self-preferencing and applying unfair access conditions; preventing users from sideloading and un-installing pre-installed apps; impeding data portability and interoperability; imposing anti-steering provisions. Yet, South Korea has recently prohibited app store operators in dominant market positions from forcing payment systems upon content providers and inappropriately delaying the review of, or deleting, mobile contents from app markets.

Despite their differences, these international legislative initiatives do share the same aims and concerns. By and large, they question the role of competition law in the digital economy. The call for action stems from the hurdles experienced by antitrust enforcers. Antitrust is considered to be falling short mainly because competition rules apply ex post and require an extensive investigation on a case-by-case basis.

With specific regards to app stores, these regulatory interventions attempt to introduce a neutrality regime with the aim of increasing contestability, facilitating the possibility of switching by users, tackling conflicts of interests, and addressing imbalances in the commercial relationship. After all, the neutrality regime is the ultimate goal of any proposal aimed at considering dominant online platforms as common carriers or public utilities.

Against this background, our new paper aims to investigate whether antitrust provisions are flexible enough to keep up with the dynamics of digital app stores and whether regulatory interventions are, on the other hand, required in order to address their unique features.

Platform and device neutrality regime

Focusing on the content of the European, German, and U.S. legislative initiatives, the neutrality regime envisaged for app stores is pursued by introducing obligations in terms of both device and platform neutrality. While the former includes provisions on app un-installing, sideloading, app switching, access to technical functionality, and the possibility of changing default settings, the latter entail data portability and interoperability obligations, and the ban on self-preferencing, sherlocking, and unfair access conditions.

Antitrust v. regulation

Despite the growing consensus over the need to rely on ex ante regulation to govern the digital markets and tackle the practices of large online platforms, recent and ongoing antitrust investigations demonstrate that standard competition law still provides a flexible framework for scrutinising several practices sometimes described as new and peculiar to app stores. It is even more surprising to note that the early and strongest regulatory initiative has been launched in Europe, despite the fact that, as also illustrated by the recent Google Shopping decision, the European antitrust framework grants significant leeway to antitrust enforcers in comparison to the U.S. scenario. Indeed, considering legislative proposals to modernise antitrust law and to strengthen its enforcement, the U.S. House Judiciary Antitrust Subcommittee, along with some authoritative scholars, have suggested emulating the European model by imposing particular responsibility on dominant firms by introducing the notion of abuse of dominant position and overriding several Supreme Court decisions in order to clarify the prohibitions on monopoly leveraging, predatory pricing, denial of essential facilities, refusals to deal, and tying.

By contrast, regulation appears better suited to support interventions aimed at implementing industrial policy objectives. This applies, in particular, to provisions prohibiting app stores from impeding or restricting sideloading, app un-installing, the possibility of choosing third-party apps and app stores as defaults, as well as provisions that would mandate data portability and interoperability.

However, regulatory proposals may cause unnecessary overreaching. Indeed, by questioning the core of digital platform business models and affecting their governance design, these interventions entrust public authorities with mammoth tasks that could ultimately jeopardise the profitability of app store ecosystems. Yet, they may overlook the differences between Google and Apple business models.

Further, the apparent difficulty in tackling the issue of a remedy involving product design raises doubts about the possibility for regulators to craft feasible and effective solutions. In Google Shopping, the European General Court, for instance, merely noted that, in finding that Google engaged in the favouring of results from Google’s own comparison shopping service, the Commission compared the positioning and display of Shopping Units with the positioning and display of generic results from competing comparison shopping services. As a consequence, it could be argued that, as no slots are reserved to Google’s own services, hence no discrimination is allowed, the auction mechanism is compliant, regardless of the fact that Google can outbid its rivals (see here).

Moreover, the neutrality principle cannot be transposed perfectly to online platforms. Indeed, the working of the app discovery and distribution markets differs from broadband networks as rankings and mobile services by definition involve some form of continuous selection and differentiated treatment to optimise the mobile customer experience.

For all these reasons, as opposed to the widespread nostalgia for regulation, an in-depth analysis of the most relevant anticompetitive practices carried out by app stores supports the idea that antitrust law enjoys considerable leeway in keeping up-to-date with market dynamics, providing a less intrusive and more individualised approach, which would eventually benefit consumers by safeguarding quality and innovation.

| This guest blog was written by Oscar Borgogno and Giuseppe Colangelo for the IGIR and METRO Faculty of Law Maastricht #COMIPinDigiMarkts2022 project - More blogs on Law Blogs Maastricht |

This guest blog is part of the project #COMIPinDigiMarkts2022. These blogs have been specially prepared by participating internal and external project members and focus on competition law and IP law, with particular reference to the digital markets.

-

Whither economic regulation for the digital markets: Is regulatory vacuum or regulatory capture likely?

Some conducts encountered in digital markets, e.g. killer acquisitions, self-promotion and marketing strategies, non-transparent and discriminatory interfaces, signify a need for ex ante regulation, as widely acknowledged. The European Commission, UK Government and US Senators proposed legislative...

-

Regulating Big Tech Platforms: which is the way?

As Big Tech Platforms increasingly become unavoidable actors in digital markets, there seems to be a consensus in the EU, UK and USA that legislative action must be taken to tame their power. However, there are several notable differences in the way in which they suggest to design this regulatory...