Brazil, malaria, and Cartier, the adventures of a sensor engineer

It is always great when a plan comes together, especially if it happens all at once. Rocio Arreguín Campos developed a quick and easy-to-use diagnostic tool for malaria. Together with her boss, Bart van Grinsven, she successfully tested the device in Brazil. Read their story about sensors, malaria, and lab equipment that magically transformed into a Cartier bracelet.

“After I finished my PhD on the detection of bacteria using thermal sensors, I was able to continue working at the Department of Sensor Engineering at Maastricht University, although I had to shift my focus to a new field. Having demonstrated the success of our sensor in detecting bacteria in food, we decided to switch to diagnosis”, says Rocio Arreguín Campos.

Warm blanket

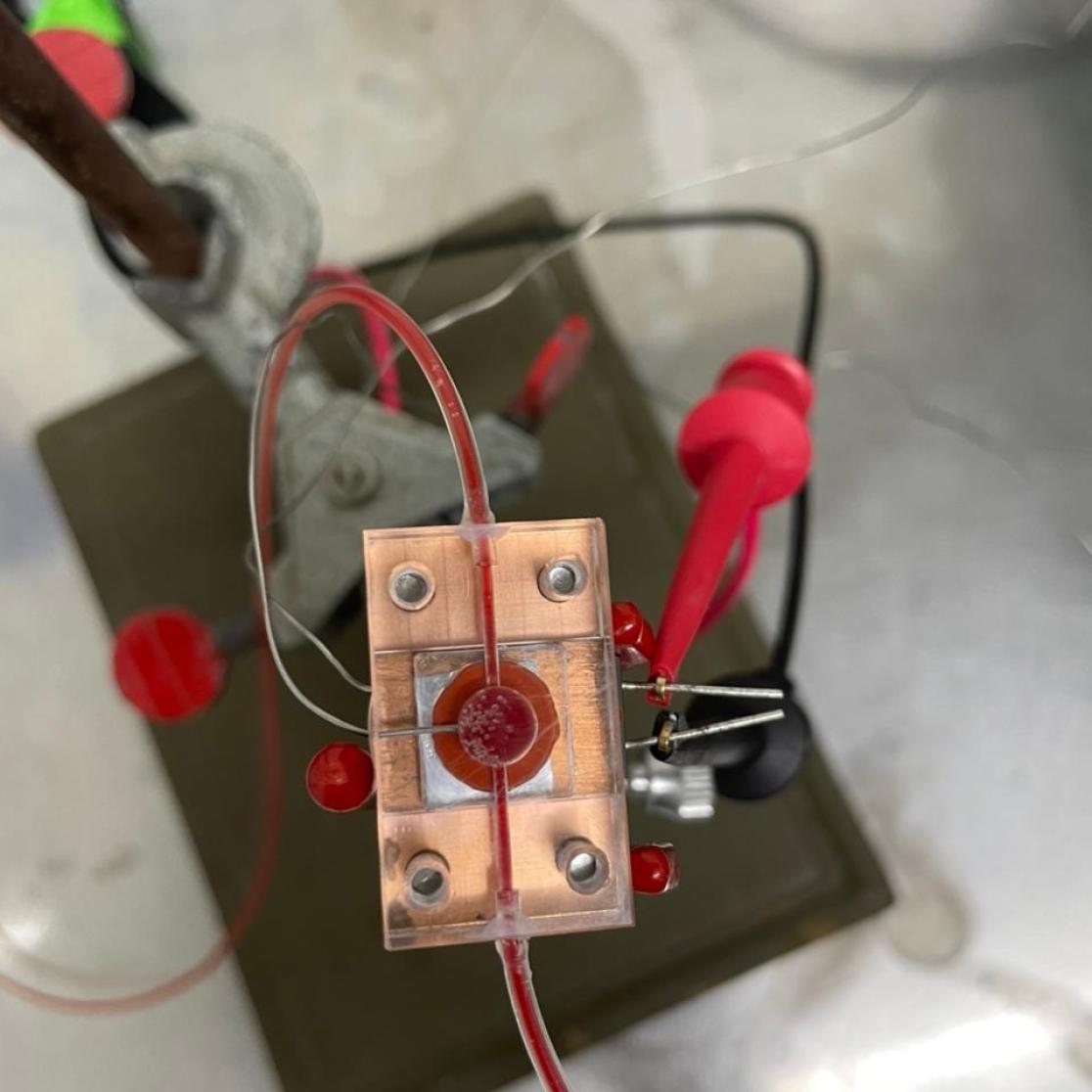

At the Maastricht lab, Rocio created a sensor that can bind to malaria-infected red blood cells. The method sounds surprisingly simple. She creates a mould by covering infected red blood cells with a liquid polymer. After the polymer solidifies, she removes the cells, leaving behind a thin plastic film with microscopic dents in which infected cells fit, but healthy cells do not. “Because a healthy red blood cell has a smooth oval shape, while cells infected with malaria have a rough, spiked surface”, she explains.

Imagine you are sitting on a couch, feeling cold. You could snuggle in under a blanket. The blanket will prevent your body heat from escaping. Rocio’s sensor works in a similar way. The polymer mould sits on a heating element. Above it, a thermal detector measures the heat that is being transferred through the polymer. When infected red blood cells get stuck in the dents, they act like a blanket, keeping the heat in. The thermal sensor will see a drop in temperature that shows the number of infected cells bound to the polymer.

Inside the package was a $12,000 Cartier bracelet instead of our lab equipment

Bart van GrinsvenBracelet

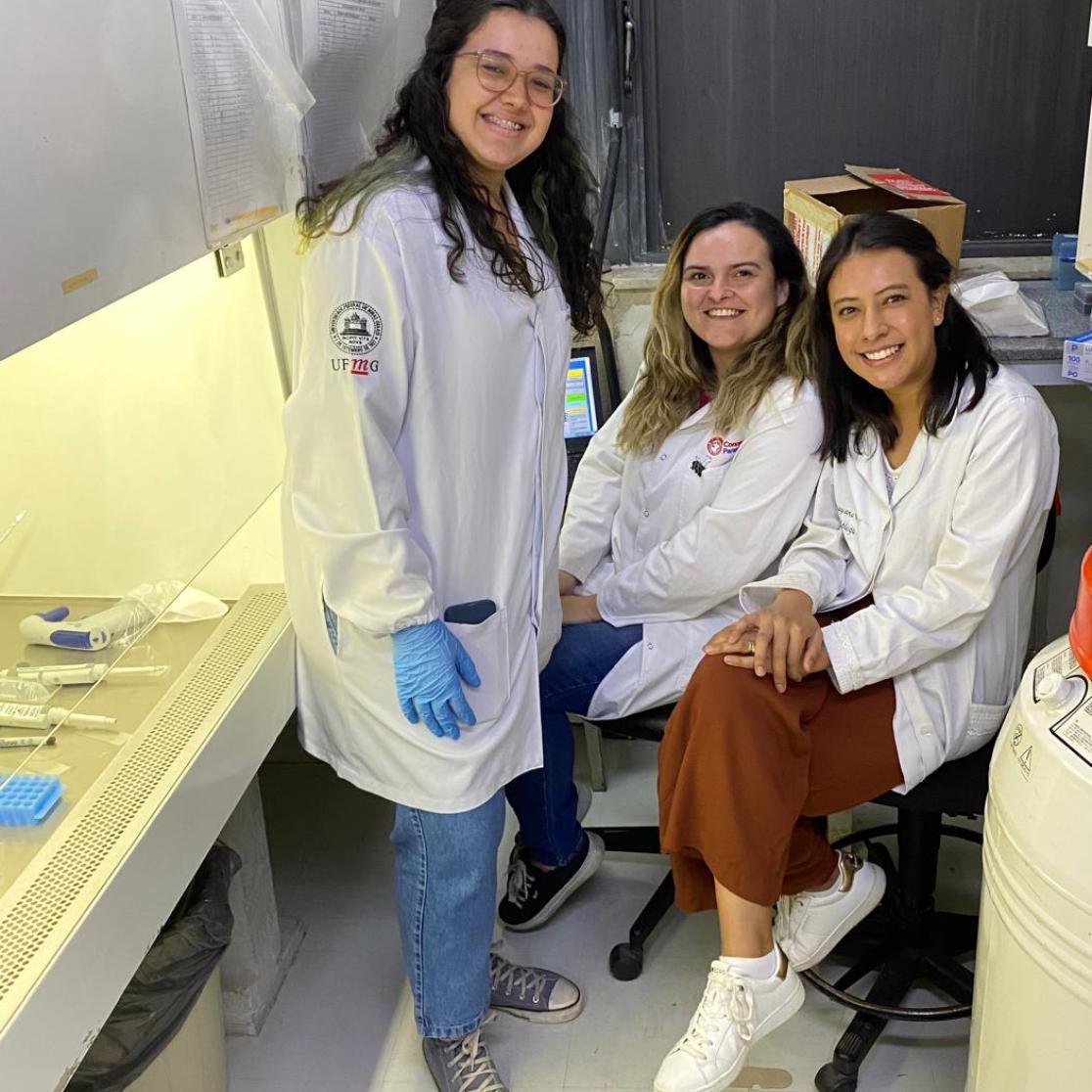

In the lab, the sensor works, but will it work using fresh, infected blood? To answer this question, Rocio and Bart van Grinsven, the head of the sensor engineering department, went to a parasitology lab in Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

“We sent a big box of equipment ahead to Brazil”, says Bart. “When I arrived, they showed me a small box, the size of a coffee cup. All of the labels from the original package were stuck on it, but inside was a $12,000 Cartier bracelet instead of our lab equipment. It quickly became clear that we had been the victims of label fraud. We handed the bracelet over to the authorities and had to borrow suitable equipment from nearby laboratories.”

Rocio had to familiarise herself with the borrowed equipment, but this did not deter her. “Meanwhile, our Brazilian colleagues cultured the most common malaria parasite by adding it to fresh blood they donated themselves.” Bart jokingly adds: “Every morning, the first one arriving would be that day’s donor.”

First blood

Because of the extensive work in Maastricht and despite the setback with the equipment, the experiments in Brazil were a success from the start. Rocio: “When we applied blood for the first time, we immediately saw a signal in the thermal sensor. Soon we figured out that the detection limit of our sensor is well within the limits required for the diagnosis of malaria”. The scientists can detect malaria even if only 0.5% of the red blood cells are infected.

Because of this success, Rocio and her colleagues want to test the sensor in patient care, comparing their results to the common lab-based malaria tests. Rocio: “The big advantage of our sensor is that it can be used at the point of care. Malaria testing is done in a laboratory environment that is not usually available in low-income countries. Some other point-of-care tests do exist; they are like Covid home tests. But they are more expensive. Also, the malaria parasites tend to mutate, which hampers the detection by these tests. Since we measure infected red blood cells, mutations do not interfere with our sensor. We even hope that the sensor will pick up cells infected regardless of the type of malaria parasite.

Malaria

Malaria parasites infect about a quarter of a billion people each year. Especially Africa is hit severely, because here your chance of surviving malaria is worst. Every year, about 600,000 people die, 94% of them in Africa.

Five closely related parasites of the genus Plasmodium can cause malaria in humans. The parasites enter red blood cells, where they multiply. When full, the cells burst, releasing new parasites that again infect and destroy red blood cells.