Liberated from the insulin syringe

Almost 150,000 people in the Netherlands suffer from type 1 diabetes. They have to inject themselves with insulin every day and face the constant threat of serious health problems. But there is good news. Aart van Apeldoorn, diabetes researcher at the Institute for Technology-Inspired Regenerative Medicine (MERLN), hopes to do away with the insulin syringe by means of an implant known as the ‘tea bag’. “Our beta cells can control blood sugar better than a syringe and pump can.”

Type 1 diabetes is a serious and debilitating disease – one that, as yet, is incurable. It is caused by a failing immune system that knocks out the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas, specifically in the regions known as the pancreatic islets or islets of Langerhans. The disease can be successfully treated through an islet transplantation. Donor organs are scarce, however, and patients run the risk of immunoreaction. This treatment is therefore only offered to a select group of patients who are in particularly bad shape.

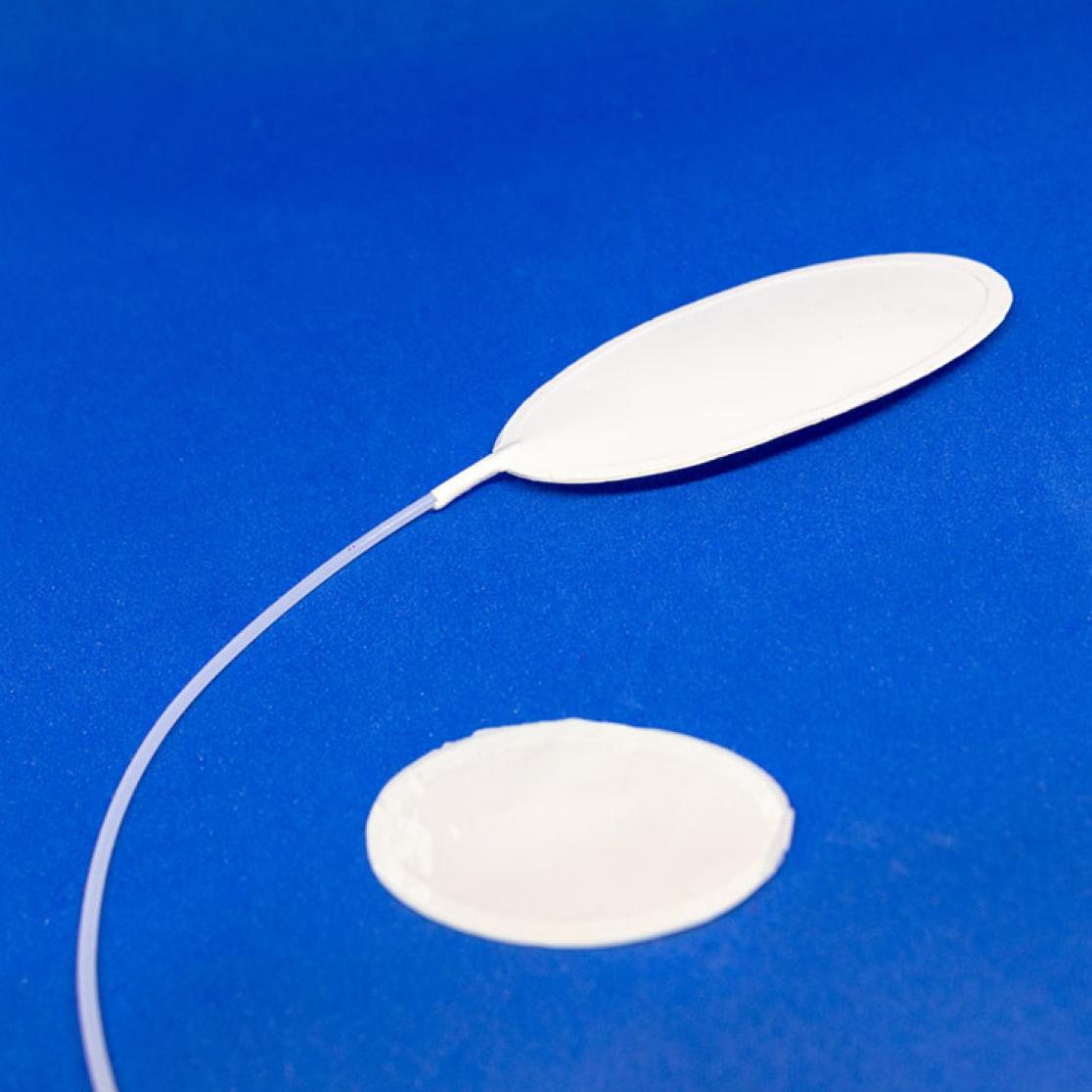

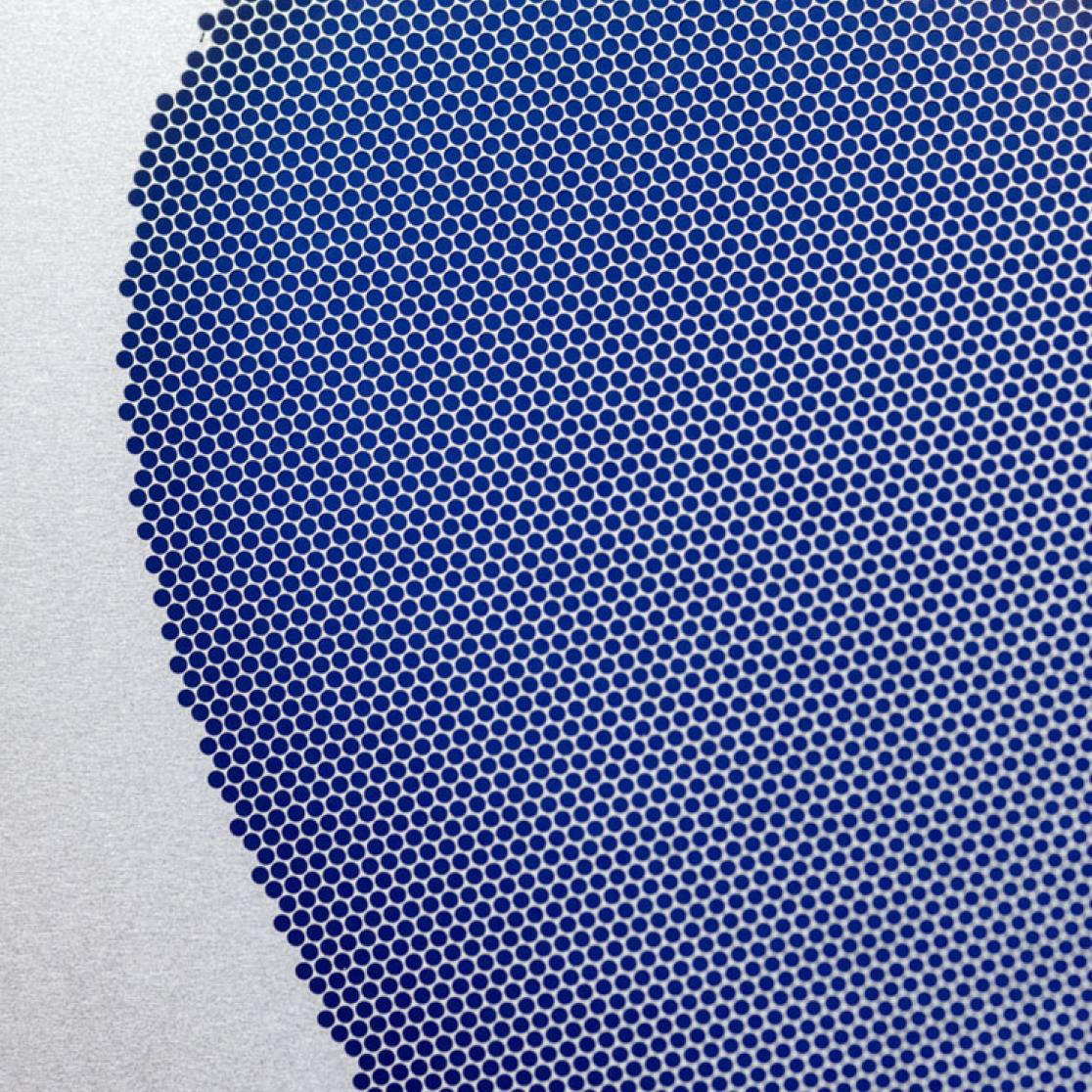

So Van Apeldoorn’s invention is all the more important. He is developing a customised implant made from extremely thin synthetic material, allowing for efficient implantation of beta cells. Patients receive, as it were, a new insulin-producing pancreas. “It’s an envelope of thin, porous layers of biomaterial – polymers – and looks like a tea bag”, Van Apeldoorn explains. “Just like tea leaves, the insulin-producing beta cells have to stay together, while the blood-sugar-controlling hormone, the insulin, can get out through the membrane.” The basic designs are currently being tested. “We’re investigating questions like: how many beta cells do we need to put in the artificial organ? How does sugar enter? Are the beta cells stimulated to release the right amount of insulin, and at what speed?”

Holy grail

Van Apeldoorn regards the insulin tea bag as an artificial organ that protects the beta cells from the immune system, allowing them to survive and thrive. “That’s the big challenge, the holy grail in regenerative medicine: the construction of a new organ.” He came up with the idea while experimenting with nanodyne biomaterials. “My first thought was the islets of Langerhans, which are neatly stacked little spheres. Could you not build a nice compact organ with them, using bioengineering tricks? That was the first step.”

Surgeons will soon practise the new transplantation technique in animal studies. Van Apeldoorn expects the first clinical tests within two years. He is optimistic: “Our beta cells will be able to control blood sugar better than is currently possible with a syringe and pump.” That said, he is reluctant to specify exactly when the implant will become available to patients. “I could say in x years from now, but if we then miss that deadline, it’s very disappointing for people.”

Collaboration

The insulin tea bag is just one of numerous findings at the MERLN institute, and the latest example of Science Plus, in which science and entrepreneurship join forces to solve social problems. Other notable innovations at Maastricht University include the development of cultured meat, killer cells against cancer and green chemistry. Van Apeldoorn himself previously worked on bone and cartilage applications, but he wanted to get more directly involved with patients. “For me, it’s important that a finding has social relevance. I’d love it if I could make a contribution, however small, to solving the diabetes problem.”

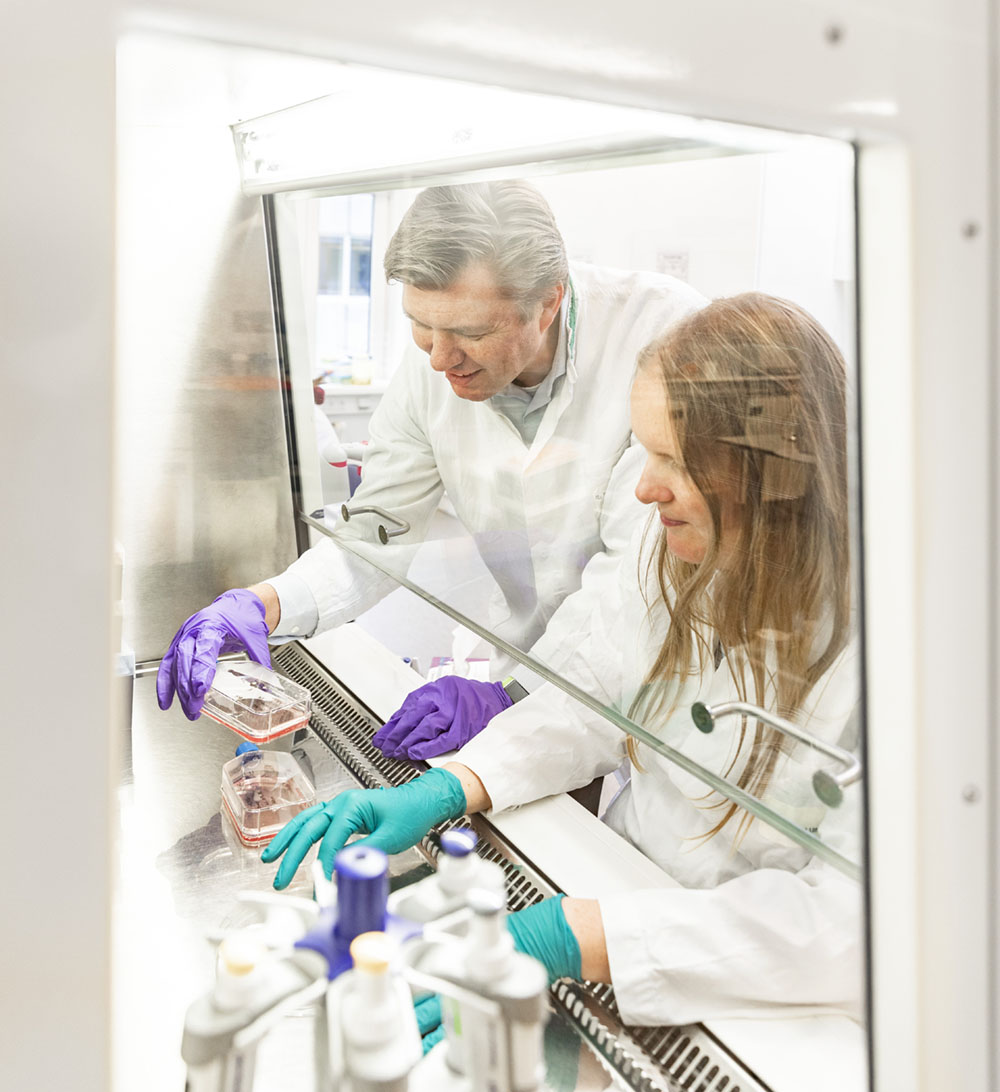

The success of his diabetes research and other MERLN innovations lies, according to Van Apeldoorn, in collaboration. “We don’t do it alone. All kinds of researchers, including cell biologists, chemists and materials scientists, are working on the insulin tea bag. We’re collaborating with the Leiden University Medical Centre, the Hubrecht Institute in Utrecht, Eindhoven University of Technology and many different companies.” The research is supported by grant providers such as the DON Foundation, the Diabetes Research Foundation (Diabetes Fonds), the RegMed XB association and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, from which Van Apeldoorn recently received almost €1 million in funding. “All that money goes towards the ongoing research.”

Cure

If the tea bag passes the clinical tests, people with type 1 diabetes will stop being patients. Still, Van Apeldoorn hesitates to call it a cure. “We’re not repairing the immune system, but the shortage of beta cells. I’d rather call it a temporary cure. Cells don’t live forever, so we’ll have to replace the implant now and then. Not very often, though: with the current transplant some patients have been independent of insulin for seven years. The aim of our treatment is to reduce the risks and increase efficiency so that a much broader group of patients can benefit from beta cell replacement therapy.”

His work continues to revolve around diabetes research. “My dream is to make a completely biological implant without synthetic materials.” This does not, however, preclude the possibility of new discoveries. “What we’re able to do – building a customised implant for beta cells and islets of Langerhans – can also be done with other tissue types. Take other hormone-producing cells or kidney cells: they too absorb and excrete substances via porous membranes. There’s plenty of freedom at MERLN to work on new things.”

Also read

-

“People just want to be treated like people”

Gera Nagelhout is, in many respects, not a typical professor. She was the first in her family to attend university, and at the age of 34 was appointed endowed professor of Health and Wellbeing of People with a Lower Socioeconomic Position.

-

Healthcare for undocumented migrants

Together with her master’s students, Milena Pavlova is investigating the access to healthcare of undocumented migrants. Her findings give cause for concern: in many countries, this group has no or little access to healthcare.

-

Organ donation after euthanasia still rare

Due to an acute shortage of organ donors, hundreds of people die each year in the Netherlands and Belgium alone. One large group of potential donors may not even be aware that they can donate their organs: people who opt for euthanasia. For his PhD research, Jan Bollen studied the issue of organ...