Aggression, a last resort in rising sea levels

In nature, large-scale aggression is rare, but it can take hold when space and food become scarce. Researchers from the University of Amsterdam, Maastricht University, and their international colleagues show how this can happen.

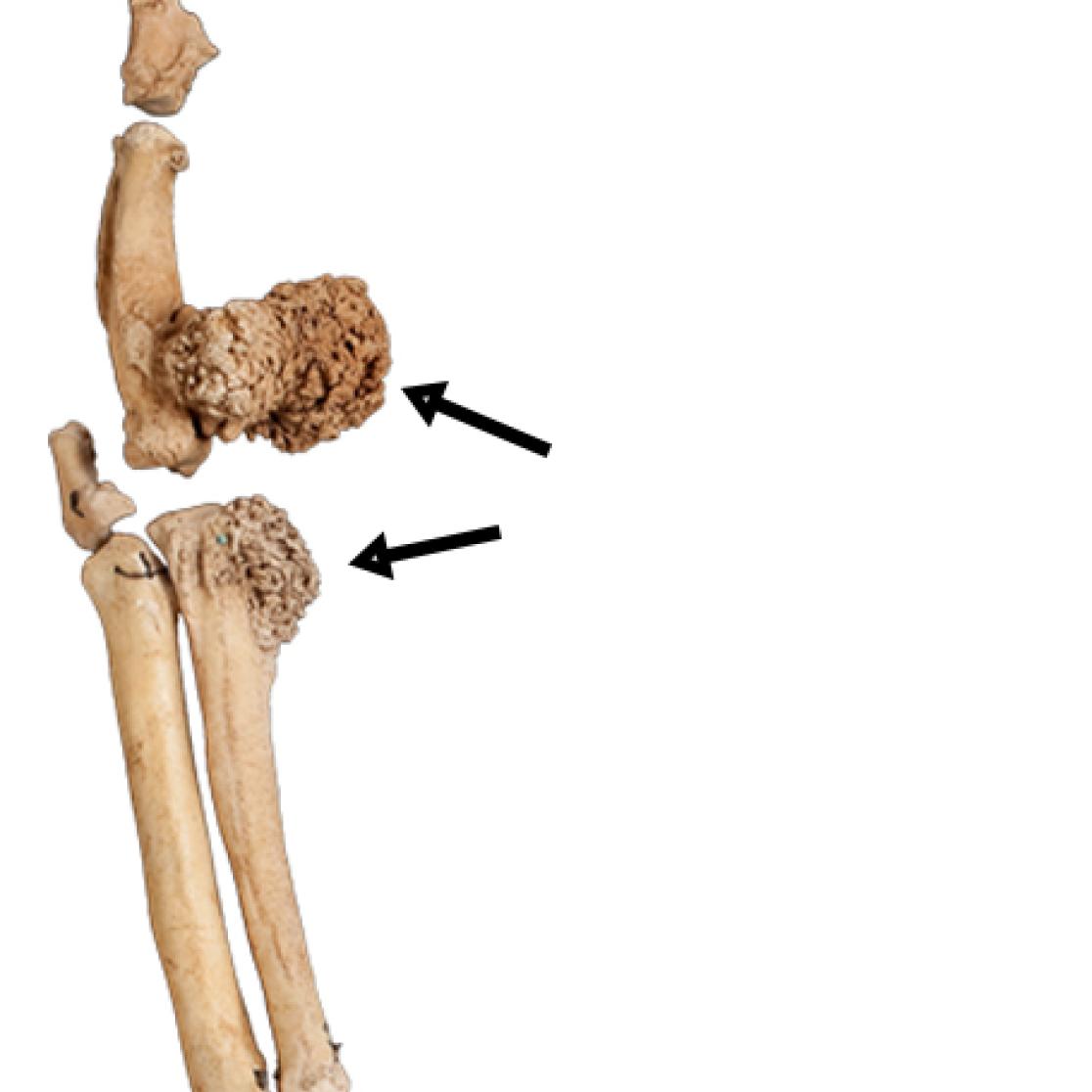

On the island of Rodrigues in the Indian Ocean once lived the Solitaire, a highly aggressive giant pigeon that went extinct in the eighteenth century. The birds were equipped with bony protrusions on their wing skeletons, which they used to fight each other in defence of their territory. The researchers refer to these protrusions as “boxing balls.” Excavations on Rodrigues reveal the damage a blow from such a “boxing ball” could cause, with broken bones being fairly common.

Aggression

On Rodrigues, all Solitaires—both male and female—were found to be aggressive and armed, unlike their closest relative, the peaceful Dodo on the nearby island of Mauritius. The Solitaire’s aggression puzzled researchers for a long time. In nature, large-scale aggression is generally a poor strategy. Fighting consumes energy and can lead to injuries or death. Usually, aggression is confined to a few individuals within a group, such as rutting stags. Aggressive behaviour also often serves to deter others, in an attempt to avoid actual fights.

Sea Level

Interdisciplinary research by palaeontologists, evolutionary biologists, and geologists shows that the land surface on Rodrigues varies greatly. During ice ages, it expands, but afterwards, as melting ice raises sea levels, the land area shrinks rapidly, by as much as 90%. The Solitaire population became constrained. The most aggressive birds retained their territory and gained dominance. They passed their genetically determined aggression to their offspring, and eventually, all the birds became aggressive. Since this phenomenon repeated after each ice age, the population remained aggressive.

Humans

The research yielded another striking finding. The scientists can mathematically demonstrate that there is a critical threshold; if this is exceeded, aggression becomes an irreversible dominant trait in that population. They speculate that a similar phenomenon might occur in other species, perhaps even in humans.

Read the full article in iScience:

Also read

-

Ron Heeren appointed fellow of the Netherlands Academy of Engineering

Professor Ron Heeren, distinguished university professor at Maastricht University (UM) and director of the Maastricht MultiModal Molecular Imaging Institute (M4i), was appointed as a fellow of the Netherlands Academy of Engineering (NAE) on Thursday 11 December.

-

UM builds open education and digital literacy into BKO/UTQ

Maastricht University is taking a practical step to support early-career teachers: open education and digital literacy will be built more firmly into the BKO/UTQ.

-

Companies unlock Maastricht University’s hidden talent

@Work students serve as a bridge between academia and industry, helping companies recognise the university’s strengths. “We’re a hidden gem that’s gradually being discovered, as more and more people learn that we are one of the largest academic data science and AI programmes in the Netherlands