White Walkers, Red Lines: The IHL Case Against the Night King

Fictional battles have long served as a mirror for real-world anxieties about war, technology, and the limits of law. Season 8, Episode 3 of Game of Thrones, “The Long Night,” provides an opportunity to test the boundaries of international humanitarian law (IHL) by confronting its most fundamental assumptions yet again.

“The Long Night” is set at Winterfell, the ancestral stronghold of House Stark in the North of Westeros. As the forces of the living brace for a siege, an unprecedented alliance forms among previously warring human factions - Starks, Targaryens, the Unsullied, Dothraki horsemen, and remnants of the Night’s Watch. Their enemy is the Night King, an ancient supernatural being created by the “Children of the Forest” as a weapon gone awry. The Night King commands a vast army of “wights” (reanimated corpses), White Walker lieutenants, and even a resurrected dragon. His singular purpose: the extinction of all living things. The episode unfolds entirely during a night of unrelenting battle. Civilians are hidden in the crypts below the castle while soldiers, outnumbered and outmatched, man the ramparts above.

This article examines the Battle of Winterfell as a thought experiment in IHL. It examines whether IHL can, or should, apply when a party, in this case, the Night King and his “undead” army, lacks legal personality, moral agency, or the capacity for compliance. Drawing on recent debates about lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS), the piece explores the Night King’s forces as an allegory for a future where war is increasingly automated.

This analysis proceeds on the assumption that Westeros is a party to the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols; without such a premise, applying international humanitarian law to this fictional setting would be impossible. For a fuller exploration of IHL and popular culture in Westeros, see also my companion article, “Dracarys and Law,” which puts the destruction of King’s Landing on trial under the laws of war.

The Ontology of Armed Conflicts

IHL, as codified in the Geneva Conventions and articulated in customary international law, is designed to regulate situations of “armed conflict” between states and/or organised armed groups. Ordinarily, the first step in any IHL analysis is the conflict classification as an international armed conflict (IAC) – hostilities between states, or a non-international armed conflict (NIAC) – hostilities between a state and organised armed groups, or between such groups themselves within states (Common Article 2 and 3, Geneva Conventions). According to the seminal Tadić decision (para. 70) by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, a NIAC exists where there is “protracted armed violence between governmental authorities and organised armed groups or between such groups within a State,” with both the intensity of violence and organisation of parties as minimum requirements.

But can there be an armed conflict where one “party” is not human at all, let alone a state or organized armed group? IHL assumes that all parties are entities with the capacity for legal agency, that is, they can bear rights and duties and can, at least in principle, be held accountable for violations (ICRC Commentary, Common Article 3; Tadić, para. 94). The Night King’s army, despite its organisation and operational capacity, is fundamentally non-human. Its members are not “persons”, and the Night King himself, though conscious and capable of strategic planning, is not a human actor but a creation of the Children of the Forest, a kind of artificial general intelligence (AGI), gone “rogue” in fantasy form. This analysis also supports a conditional analogy with LAWS, with the Night King and his generals functioning as a kind of super-sophisticated algorithm directing the army.

The “undead” are, in effect, sophisticated weapons, animated extensions of the Night King’s will. When he is destroyed, his army collapses, highlighting their function as mere means of warfare rather than actors with legal status. Under the principle of distinction, commanders must distinguish between civilians and combatants (ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 1). Nevertheless, in this case, IHL does not bind the undead; they cannot be protected by or held responsible under its rules. The situation is more extreme than any “asymmetric conflict:” it is not simply the law-bound versus the lawless, but humanity against something that stands outside the law entirely. Virtually any means to defeat them would, in principle, be permissible, since there is no legal adversary to whom IHL’s traditional limitations apply.

The Obligation to Protect Civilians

IHL is not just about regulating conduct toward the enemy. It also imposes positive duties on belligerents to protect those under their control, especially civilians. Regardless of the adversary’s status, commanders must take all feasible precautions to spare civilians from the effects of hostilities and are prohibited from using them as shields or exposing them to unnecessary danger (Customary IHL, Rule 22).

In the real world, the UN Security Council, through resolutions like 2286 (2016) and 1265 (1999), has called for the protection of civilians and adherence to IHL “to the fullest possible extent,” even when the legal status of the conflict is in question. While no such supranational authority exists in Westeros, the principle remains instructive: whenever organised violence endangers noncombatants, the underlying humanitarian aims of IHL should guide the conduct of all organised actors. The continued applicability of these duties, irrespective of the legal status of the enemy, is not affected by the legal vacuum in which they may operate.

Inside Winterfell, these obligations translated into concrete action: civilians were sheltered in the crypts, as far removed as possible from the fighting. Commanders allocated food, light, and protection in advance, fulfilling the customary IHL requirement to safeguard civilians under their control (APII, Art. 17; Customary IHL, Rule 129). IHL’s raison d’être is not reciprocity but the protection of the vulnerable. The living parties at Winterfell had to uphold IHL not for the benefit of the undead, but to protect the lives of their people.

Contemporary Implications: Autonomy, Accountability, and the Limits of IHL

The Night King’s undead army, while highly organised and engaged in large-scale violence, simply does not meet the basic criteria for party status under IHL: it is not a state, nor an organised armed group capable of bearing legal obligations. The essence of IHL is its application to “conflicts” between entities with legal agency; where that is lacking, the framework collapses. The practical result is that the protections and obligations under IHL are formally suspended, and the focus shifts instead to protecting civilians under other bodies of law or through moral and practical measures.

This fictional scenario is more than a thought experiment; it directly engages today’s legal dilemmas. As militaries experiment with LAWS, the international legal debate does not question whether IHL applies (UN CCW LAWS Group of Governmental Experts), but whether the use of LAWS is compatible with IHL’s requirements on the means and methods of warfare, and whether meaningful human control and accountability can be maintained (see, e.g., ICRC position, 2023).

Real-world cases, like cyberattacks attributed to non-state actors or theoretical future AI-driven hostilities, force us to confront the law’s outer boundaries. The Battle of Winterfell, in all its dramatic exaggeration, reminds us that the ultimate test for IHL is not the nature of the adversary but the resolve of the law-bound to uphold dignity, restraint, and accountability, even in the face of existential, inhuman threats.

Law for the Living

The Battle of Winterfell dramatises an extreme test case for international humanitarian law: what happens when one side to a conflict is not only unbound by legal norms, but is incapable of bearing rights or responsibilities at all? The scenario underscores whether IHL can (or should) adapt to confront adversaries that defy traditional legal personhood, be they autonomous weapon systems, cyber entities, or other non-human actors.

Ultimately, IHL may falter as a matter of formal applicability when the adversary falls outside its definitional scope (Common Article 3; Tadić, para. 70-71). Yet its animating spirit, the imperative to protect civilians and to discipline the conduct of organised human forces, remains vital. The obligations of distinction, precaution, and proportionality are not merely legal formalities but the final bulwark of humanity when confronted by the unthinkable.

As new technologies and adversaries continue to push the boundaries of war, the story of Winterfell serves as an allegory and a warning. The future of armed conflict will demand not only legal imagination but renewed commitment to the foundational purpose of humanitarian law: to ensure that, even when the enemy cannot be held accountable, the living still must protect their own.

* About the author: Davit Khachatryan is an international lawyer, researcher, and lecturer. He specialises in alternative dispute resolution, investment law, and public international law, with a focus on international humanitarian law, use of force, and security. Davit frequently participates in research and policy discussions and regularly contributes to academic and professional platforms, sharing insights on public international law, dispute resolution, and emerging issues in global security. Get in contact.

-

Bye bye culture – enter norms and codes?

Fond of regulations as they are, jurists could nonetheless have an interest in learning about their origins and current proliferation, and Olivier Roy’s latest book addresses this question by offering a thought-provoking reflection about the path that contemporary culture has taken.

-

A Fan’s Guide to Football’s Lex Sportiva: How the CJEU is Changing the Game

On April 28th, I published my very first podcast, which dived into the iconic field of Sports Law. This work was the product of an “Honours Programme Personal Project” supervised by Dr. William Bull. As I look back on this experience, I am honored to share some of the takeaways which Dr. Bull and I...

-

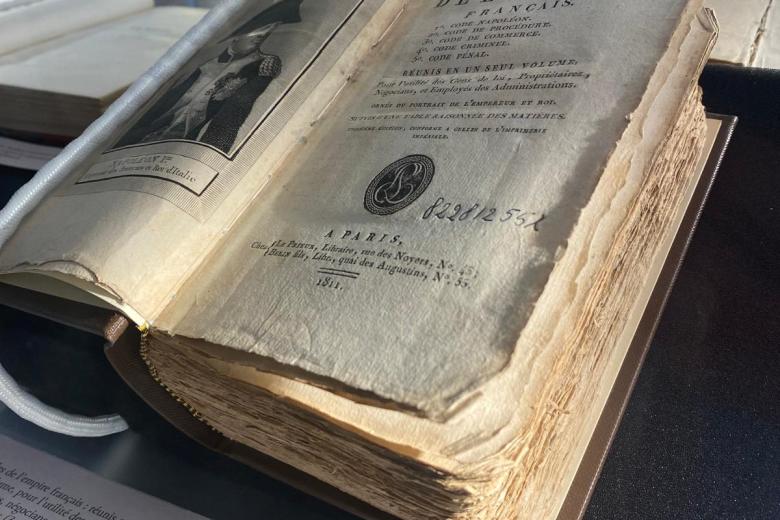

Object- and Problem-Based Learning (OBL & PBL): A Fruitful Amalgamation for the Development of Legal Education

Patrons at the Arthur W. Diamond Law Library at Columbia University (USA) can encounter a duplicate of an automobile wheel that relates to the 1916 court case heard by Judge Benjamin Cardozo in MacPherson v. Buick Motor Co. The wheel is an object that hangs on a wall on the fourth floor of the...