Fostering impunity: Burundi’s withdrawal from the International Criminal Court

Instead of protecting the victims of Burundi, the current government shields those who are responsible. The problem with such impunity is that it de facto “legalizes” violence as no accountability is created.

Shoot the messenger

On the 25th of October 2017, the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), authorised an investigation into the situation in Burundi because of alleged crimes against humanity perpetrated by state agents and associated groups against political opponents and the civilian population. Two days after this investigation had been authorised, on the 27th of October 2017, Burundi became the first country to leave the ICC. The decision to withdraw had already been made in 2016, but it now finally took effect. In an explanation, the Burundian presidential office noted that “the ICC has shown itself to be a political instrument and weapon used by the west to enslave other states” and that the withdrawal from the court is “a great victory for Burundi because it has defended its sovereignty and national pride.” Stanley Cohen, who wrote extensively on how perpetrating regimes counter critique, would probably have designated this rhetorical strategy of the Burundian presidential office as ‘shooting the messenger’. The strategy involves attacking a critical institution, in this case the ICC, by questioning its objectivity and reliability in order to cast doubt on the truth of allegations while also questioning its right to criticize. The withdrawal signals the next step in a downward spiral of impunity that will have disastrous consequences for the country and its people. Fabian Baciryanino, a member of parliament who opposed the withdrawal, explains that leaving the ICC was “no more, no less, than inciting the Burundian people to commit more crimes.”

A country in turmoil

According to the prosecutor of the ICC there is a reasonable basis to believe that state actors engaged in a widespread and systematic attack against the Burundian civilian population. The violence targeted those opposing the ruling party of President Pierre Nkurunziza (CNDD-FDD). Nkurunziza is in office for a third term since 2015, an arrangement which according to his opponents violates the constitution and the peace agreement that ended the civil war in 2005. Shortly after Nkurunziza’s electoral victory, an unsuccessful coup d'état was attempted and in a reaction Nkurunziza began purging his government and the country of opponents resulting in widespread human rights violations, such as, unlawful killings, torture, disappearances, and restrictions on freedom of expression. To date, hundreds of people were killed, thousands have been arrested and more than 200.000 people were forced to flee the country.

Structural impunity

The choice to withdraw from the ICC fits a broader historical development of impunity in Burundi. The country has a long history of ethnic conflict causing numerous casualties and immense suffering. The massive crimes that have been perpetrated over the last 50 years have never been appropriately addressed – leaving the victims without justice and redress. Over time, this impunity has contributed to new cycles of violence. In the past, peace agreements have been installed, but the accompanying amnesty arrangements have come at the cost of justice. Currently, the dynamic is not much different. It is telling that according to Burundi’s Minister of Justice Aimee Laurentine Kanyana, the government will not cooperate with the ICC investigation.

Instead of protecting the victims, the current government shields those who are responsible. The problem with such impunity is that it de facto “legalizes” violence as no accountability is created.

| More blogs on Law Blogs Maastricht |

-

C.A.R. MoerlandMore articles from C.A.R. Moerland

C.A.R. MoerlandMore articles from C.A.R. MoerlandRoland Moerland is Assistant Professor of Criminology and Law at Maastricht University. He is the director of the Forensics Criminology and Law Master Program and the co-director of the Maastricht Centre for Human Rights.

Other blogs:

Also read

-

The well-known British James Bulger case is ‘celebrating’ its 25th anniversary. This revives the debate on how we should deal with children suspected and convicted of serious crimes.

-

On 21 December the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) held its official closing ceremony. The Tribunal is thereby a thing of the past. But it lives on in the countries of the former Yugoslavia, first and foremost in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), but also in Serbia and...

-

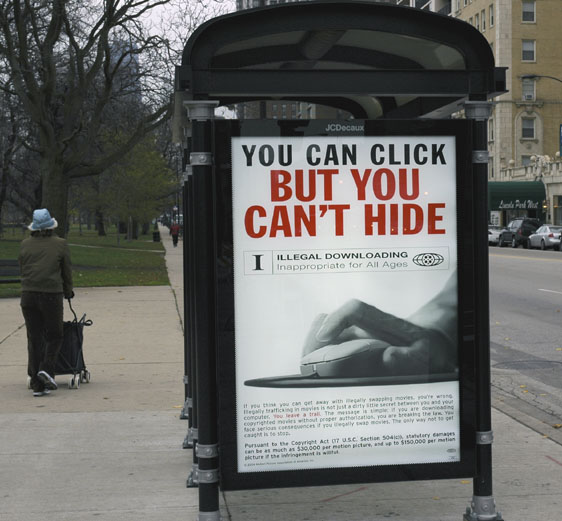

Where in 2010, about 40 per cent of the population downloaded music, the figure is now a quarter, partly because of the arrival of Spotify. The best strategy to avoid illegal downloading, according to Bastiaan Leeuw, is a mixture of punishment and temptation.