Provisions on access to algorithms and datasets in the digital markets act proposal

While the role of access to data and algorithms in digital markets is debated in scholarly literature, it is evident that there are circumstances in which it is necessary to scrutinize databases, algorithms, and source code that are used in digital services for the purposes of the enforcement of the relevant regulation. The question which this post aims to answer is how does the legislative proposal of the Digital Markets Act (DMA) approach these needs in regard to the structure of competition in digital markets. The main purpose is to provide a better understanding of the regulatory act proposed by the Commission, and in particular, the provisions of DMA that include solutions which aim to ensure access to databases and algorithms used by big tech companies.

- Articles 19 and 21 of the proposal of DMA directly identify databases and algorithms as well as explanations on algorithms and databases as specific types of information that can be requested by the Commission.

- Neither the term ‘database’ nor ‘algorithm’ is defined in the DMA. This may limit the effectiveness of including this provision in the proposal, as the undertakings may e.g. provide general descriptions of the algorithms and refuse access to the source code.

- The elements of the provisions which concern access to algorithms and datasets are separated from the provisions on access to information. This may cause problems if algorithms and datasets are not directly mentioned in a particular context. Thus, it would be more efficient to provide a broad definition of information, with an open catalogue of examples such algorithms, data and datasets, and source code.

Who is covered by the DMA’s provisions regarding access to datasets and algorithms?

DMA focuses on the regulation of core platform services providers: online intermediation services, online search engines, online social networking services, video-sharing platform services, number-independent interpersonal communication services, operating systems, cloud computing services, advertising services, and, in particular, the biggest providers of these services (gatekeepers). However, in terms of ensuring access to algorithms and databases, it refers to undertakings and associations of undertakings. This is understandable, since ensuring the access is supposed to allow the Commission to monitor, implement and enforce the rules laid down in DMA, and thus the undertaking to which the request for information is addressed may not yet be identified as a gatekeeper. The approach adopted in DMA can be described as technologically neutral: if the undertaking or an association of undertakings provides services identified as core platform services and, therefore, may fall into the category of ‘gatekeeper’, the Commission can request access to its algorithms and datasets, independently of what kind of technology the given undertaking uses.

Access to what and for whom is foreseen in the proposal of DMA?

The most important article of the DMA in this regard is Art 19. It allows the Commission to require, in a manner of simple request or by decision, undertakings and associations of undertakings to ‘provide all necessary information’. The article directly mentions databases and algorithms as well as explanations on algorithms and databases of undertakings as specific types of information that can be requested by the Commission. However, neither the term ‘databases’, nor ‘algorithms’ is defined in the DMA. This may limit the effectiveness of including this provision in the proposal, as the undertakings may e.g. provide general descriptions of the algorithms and refuse access to the source code.

What seems to be problematic is that Art 19(2) refers to the requests concerning ‘information from undertakings and associations of undertakings pursuant to paragraph 1’. Considering that Art 19(1) differentiates ‘information’ from ‘data-bases and algorithms’, the reference to ‘information’ in Art 19(2) might be interpreted as not including databases and algorithms. Such a distinction is supported by the content of Art 19(3)-(4). While Art 19(3) defines the conditions which must be fulfilled by simple request made by the Commission, Art 19(4) refers to two types of decisions that can be issued by the Commission requesting access to the relevant information. The first type concerns, again, information. The second type refers to decisions which require undertakings to provide access to its databases and algorithms. These decisions should state legal basis and the purpose of the request, time-limit for providing the access, and information about the penalties for not complying with the request. Moreover, such decisions may impose periodic penalty payments. It also seems that only this type of decisions should include the information that the undertaking has the right to judicial review of the decision by the Court of Justice of European Union.

Information collected based on, among others, Art 19, can be used only for the purpose of the DMA. This begs the question whether it would be possible for the Commission to, firstly, use the algorithms or datasets in other types of proceedings – if they were perceived as something different to information. Secondly, it raises concerns regarding situations in which the Commission would identify uncompetitive behaviour which is not covered by the DMA. In the light of the DMA’s provisions, it seems necessary for the Commission or national competition authorities to collect the relevant information once again.

Next to the possibility of requiring access to algorithms and databases by the Commission that the DMA foresees in Art 19, Art 21 broadens the scope of the access to include auditors or experts appointed by the Commission. While based on Art 19 the Commission seems to be allowed to require the relevant information at any time, even prior to opening a market investigation or a proceeding, Art 21 concerns on-site inspections at the premises of an undertaking or association of undertakings. During on-site inspections the Commission and auditors or experts appointed by it may require access to and explanation on, among others, the IT system, algorithms, and data-handling. Such an inspection should be ordered by the Commission which, among others, specifies the date of the inspection. The fact that the inspections would have to take place after informing the undertaking of their dates may limit the effectiveness of this tool.

Concluding remarks

What is crucial in the proposal of DMA is the terminology. While the DMA mentions access to algorithms and datasets directly, one can wonder whether it is the right solution. None of these terms is defined in the proposal, which blurs the scope of permitted access, e.g., in terms of understanding what is an algorithm and whether it is possible to access source code if only the term algorithm is mentioned in the given provision. Moreover, elements of the provisions which concern access to algorithms and datasets are separated from the provisions on access to information which may cause problems if algorithms and datasets are not directly mentioned in a particular context. Thus, it would be more efficient to provide a broad definition of information, with an open catalogue of examples such as algorithms, data and datasets, and source code.

Moreover, the proposal shows that the Commission favours the regulatory solutions which replicate to a great extent the ones existing in competition law. They provide this institution with a power to enforce the proposed regulations and, to enable such an enforcement, the power to request necessary information. Such a regulatory strategy leaves us with the question whether the Commission will be able to efficiently use the powers it is about to acquire and, on a more general note, whether the focus on solutions strongly inspired by the ones developed in the context of traditional economy will prove adequate for combating challenges linked to the digital one.

| This guest blog was written by Joanna Mazur for the IGIR and METRO Faculty of Law Maastricht #COMIPinDigiMarkts2022 project - More blogs on Law Blogs Maastricht |

This guest blog is part of the project #COMIPinDigiMarkts2022. These blogs have been specially prepared by participating internal and external project members and focus on competition law and IP law, with particular reference to the digital markets.

Other blogs:

Also read

-

In its fining decision of 14 September 2021 regarding Samsung, the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM) imposed a fine of over EUR 39 mln on Samsung Electronics Benelux B.V. (Samsung) (the Decision). According to ACM, Samsung coordinated the retail prices of Samsung television sets...

-

Digital platforms are one of the key developments in facilitating industry 4.0 and are at the center of the multifold benefits the consumers derived through this. An important feature of the digital platforms is the presence of high sunk costs and low marginal costs (UNCTAD, 2019). This occurs since...

-

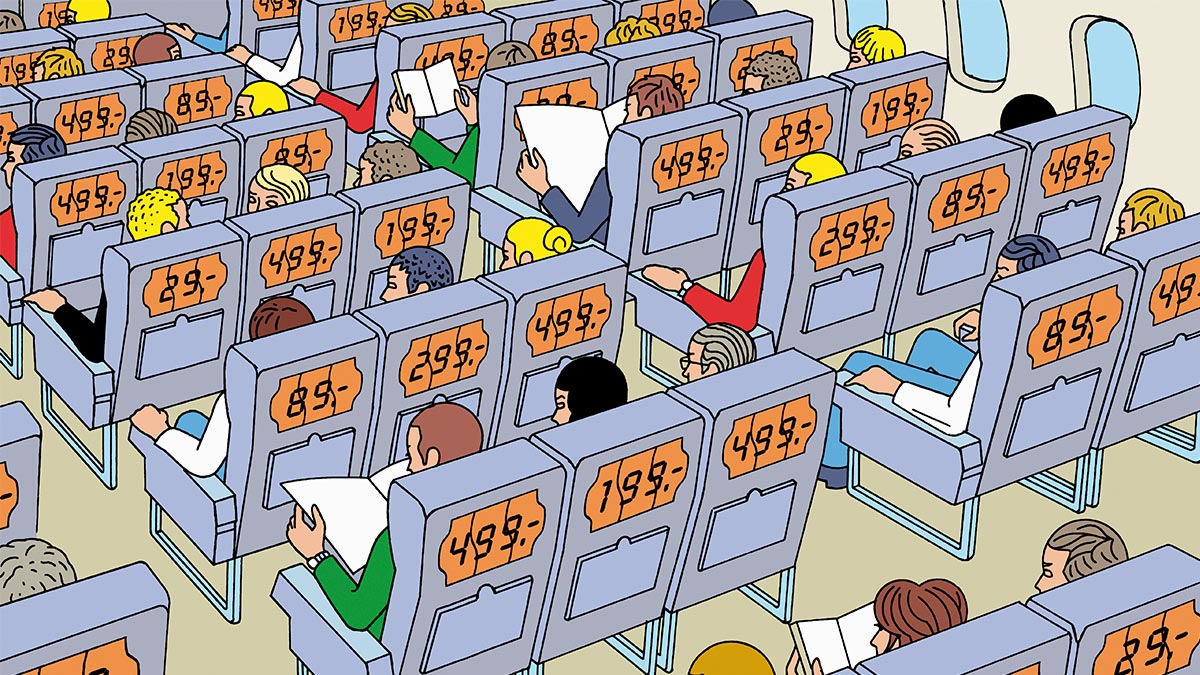

Digitalization has gradually changed business models and reshaped human lifestyles. The rise of business models based on the collection and processing of consumer data allows undertakings to charge business customers and final consumers different prices for the same goods or services, offered at...