Week from hell

Theresa May’s favoured Brexit deal is finished. The question remains when the Prime Minister will finally be prevailed upon to understand this reality – and when Parliament will finally take charge of the process.

Summary: Theresa May’s trials and tribulations continue with withering criticism of the Draft Withdrawal Agreement, whilst the Prime Minister must battle intra-party opponents, deal with an indecisive opposition and struggle with persuading fellow EU leaders to improve on the DWA – all the while the opposition dithers and fails to exploit the vulnerabilities of the Conservative Party. Finally, it will be time to reflect on the only solution to the current impasse.

______________________________________________________________________

For Theresa May, the last seven days were a week from hell. First, she continued to face criticism for the Draft Withdrawal Agreement that her former Brexit Secretary Dominic Raab had negotiated in Brussels – and then resigned over. The central points of contention included: the extendable transition period subsequent to the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union (EU); the financial settlement over Britain’s remining budgetary obligations; the residual jurisdiction of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) over the terms of the Draft Withdrawal Agreement (DWA; especially, but not limited to the rights of EU nationals remaining in Britain); and, most crucially, the so-called Irish backstop – a temporary administrative solution retaining the entire United Kingdom in a customs union with the EU until such time that both sides are able to agree on the terms of a final trade agreement, especially in light of the stated aim (of both sides) to preserve the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. The agreement was relentlessly criticized by the united opposition, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) from Northern Ireland, Conservative backbenchers supporting the United Kingdom’s continued membership of the European Union, and Conservative MPs who are looking for a complete rupture from the EU. Next, the opposition Labour Party demanded the release of the Attorney General’s full legal advice regarding the DWA.

Fuelled by the lack of support on all sides, Prime Minister May realized that her chances of successfully navigating the DWA through the House of Commons were virtually nil, and cancelled the “meaningful vote” in the House of Commons. This, in turn, led to increased dissatisfaction within the hard right of the Conservative Party in the House of Commons, which promptly decided to table a no-confidence motion in May in her capacity as Conservative Party leader. The no-confidence motion, voted on by all MPs of the Conservative Party, was defeated by a margin of 200-118, but left May teetering on the brink of collapse. These are the facts. But what are the implications? Let us take each of the latest developments, reflect on them and examine the likely consequences for the United Kingdom and the European Union – and then make the pivot towards the only solution that can fix this mess.

Incalculable: The Attorney General’s Legal Advice

Upon bringing home the Draft Withdrawal Agreement, running over 535 pages, and the Political Declaration on the intended future UK/EU relationship, Parliament subjected the DWA to closer scrutiny - the Labour Party, under its leader Jeremy Corbyn, and other opposition leaders subsequently demanded sight of the legal advice provided to the Prime Minister by the Attorney General Geoffrey Cox. The government’s chief law officer had long resisted having the advice disseminated to the wider public. However, in an extraordinary move unknown in the United Kingdom (though already seen in other Commonwealth jurisdictions, including Canada), Parliament held Her Majesty’s Government in contempt of Parliament – thus successfully compelling Leader of the House of Commons, Andrea Leadsom, to perfunctorily announce that the Attorney General’s legal advice (“the Legal Advice”) would be released in short order. What it revealed was the deep cognitive dissonance between Prime Minister May’s public position of attempting to make Brexit a worthwhile endeavour, and the inconvenient truth of the complexities involved with extricating a major industrial nation like the United Kingdom with a major legal, commercial and political endeavour it was intertwined with for 43 years.

The following will address the Legal Advice in respect to the DWA Protocol on Northern Ireland (“the Northern Ireland Protocol” (page 301 onwards)). It confirmed that the “backstop”, the temporary arrangement designed to avert the need for a traditional “hard” border” between the Republic of Ireland (which remains firmly committed to its EU membership) and the British province of Northern Ireland (which is scheduled to leave the European Union, alongside the remainder of the United Kingdom, on 30 March 2019), would introduce a distinction between Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales) and Northern Ireland on the other. The backstop is also designed to avoid the EU Single Market – easily one of the Union’s principal tenets – from being undermined by British goods permitted to enter EU customs territory without the necessary customs formalities.

In concrete terms, whilst the entire United Kingdom (Great Britain and Northern Ireland) will form a single customs territory for the purposes of a (temporary) customs union with the European Union, the arrangements will apply differently in Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Northern Ireland will remain in both the EU Customs Union and the EU Single Market on Goods – requiring supervision of its compliance with the EU’s customs rules by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) and the European Commission (para 7 of the Legal Advice). This would allow goods from Northern Ireland to freely circulate within the EU, thus rendering the need for a hard border with the Republic of Ireland moot – and preserving the central operating premise of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement ending the de facto civil war in Northern Ireland. Meanwhile, Great Britain would enter into a separate customs union with the EU and would ostensibly no longer by subject to CJEU jurisdiction – but would henceforth be treated as a third country, necessitating customs checks between Great Britain and Northern Ireland for any goods passing between these two entities (para 8 of the Legal Advice). Additionally, Great Britain would have to abide by a range of EU regulatory standards in fields like competition, labour and competition law (with the major area of state aid aligned with the jurisprudence of the CJEU).

Bound Forever?

Next up, the Attorney General also addressed the duration of the backstop agreement. He acknowledges the generally stated position, namely that the arrangement is supposed to be temporary in nature and scheduled to conclude upon the signing of a successful agreement governing the future EU/UK relationship (para 12 of the Legal Advice). However, given the protracted and acrimonious nature of the withdrawal negotiations ever since the Article 50 notification was given by Prime Minister May, the question what would happen if the EU and UK failed to reach a post-Brexit agreement appears legitimate. The Attorney General concluded that Article 1(4) of the Northern Ireland Protocol essentially premised the agreement remaining in force until a subsequent EU/UK post-Brexit agreement was in place – crucially, under international law, the Protocol would remain effective even in the event of a complete breakdown in talks between the two sides (para 16 of the Legal Advice). Compounding this problematic conclusion, the Attorney General further concluded that the mechanism on the review of the Northern Ireland Protocol was somewhat superfluous, as its termination would only be possible upon mutual consent of the UK and the EU – and only likely to be used in the event of a post-Brexit agreement being concluded anyway.

Crisis of Confidence

The publication of the Legal Advice led to the next act of the Brexit drama. The hard right of the Conservative Party, clustered around the European Research Group (ERG) faction led by North Somerset MP Jacob Rees-Mogg, was incensed about the Northern Ireland Protocol. So was the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), the minor political force propping up Prime Minister May’s minority government in the House of Commons by virtue of a confidence-and-supply agreement. The reason? The Northern Ireland Protocol and the backstop arrangement, especially its creation of a de facto (if not de jure) regulatory border between Great Britain and Northern Ireland – thus treating the latter differently than the rest of the United Kingdom. The prominent role to be played by the CJEU and the financial settlement of the UK’s obligations to the EU raised further red flags for the Eurosceptic, pro-Brexit hard right. At the same time, the minority of Conservative MPs still vociferously mounting the case for a close EU/UK relationship opposed the DWA because, in their view, the UK would be left as a rule-taker, waiting for the proverbial fax from Brussels to align its legislation with the latest stipulations by the European Parliament and Council, or the jurisprudence from the Court of Justice – without the benefits of full membership, and whilst still obliged to make financial commitments until the end of the transition period. With the Labour Party and the other opposition parties also opposed, Prime Minister May pulled the final ratification vote in the House of Commons.

In a statement to the Commons, she acknowledged that the deal would have been soundly defeated. Naturally, this was seen as a sign of weakness by the Conservative Party’s hard right, which finally got the minimum of 48 signatures from the 318 Conservative Party MPs together to mount an internal no-confidence motion in Theresa May as Leader of the Conservative Party (and effectively, Prime Minister). However, considering the late stage in the Brexit negotiations, the wisdom of changing prime ministers did not appear apparent to political observers – particularly as the EU had made amply clear that no modifications to the text of the DWA would be forthcoming, regardless of who resides in 10 Downing Street. The no-confidence motion was defeated 200-118, this immunizing the Prime Minister from any further leadership challenges (within her own party, that is) for twelve months. Whilst Mr Rees-Mogg and others were left demanding the prime minister’s resignation, there is very little they can do. Meanwhile, it appears as clear as daylight that May is far from an undisputed leader in command of the Conservative Party. Moreover, the Prime Minister had to obtain the acquiescence of the majority of her MPs by promising that she will step aside by the time the 2022 general election comes around. The Prime Minister has been weakened, and it does not exactly render her in a stronger position to extract any concessions from her fellow EU colleagues.

Failure of Leadership

What has been apparent is Prime Minister May’s lack of political courage in the face of brazen sabotage by the likes of Rees-Mogg – whose position advocating a complete “No Deal” break from the EU commands the consent of a minority of Conservative MPs, a minority of the House of Commons and a minority of the British people. Mr Rees-Mogg and the ERG have been permitted to operate freely within the Conservative Party, flouting party discipline and forcing the Prime Minister into humiliating concessions to the hard right – with an amendment to the customs bill rendering a separate solution for Northern Ireland impossible being only the most egregious example. Considering the fact that the ERG has mandate on which it can base its stridency, it has made an art of winning confrontations that any leader with determination and strength would otherwise win instead. Mrs May is no such leader. However, feeling sorry for the Prime Minister is an inappropriate sentiment, for she has been the author of her own political misfortune. It is evident that her deal is dead on arrival and will not command majority support from the House of Commons. Having boxed herself in with her 2017 Lancaster House speech, she essentially failed to grasp the United Kingdom’s disadvantage and actually exacerbated it by hastily forwarding the Article 50 notification to the European Council in March 2017 – before her government and party had been brought in line and agreed on a unified course of action.

The lack of planning, coordination, a realistic assessment of the weaknesses of the UK’s position vis-à-vis the EU, or common sense (by both May and her Brexit Secretaries, David Davis and Dominic Raab) handed one advantage after another to EU Chief Negotiator Michel Barnier. What is even worse is the fact that the Conservative Party, already guilty of calling a national referendum for party political purposes, turned Brexit into a political football. Instead of resolving to pursue a cross-party approach and thus also securing the support of the Labour Party, the Liberal Democrats and the Scottish Nationalists, the Prime Minister kept engaging in trench warfare with disloyal MPs from the hard nationalist right. The EU27, already busy enough with other major crises to attend to (think Trump, illegal immigration, the rise of extremist sentiment in Italy and elsewhere, the overt defiance by the increasingly authoritarian governments in Poland and Hungary) was left shocked at the amateur antics of the British side.

Now, the British government and the European Commission have released details of their planning for a No Deal Brexit. Despite the fantasies of committed Eurosceptics, a No Deal Brexit would take a sledgehammer to the British economy, disrupt supply chains, lead to a standstill at Dover and Calais, possibly ground aircraft destined for the European mainland and the British Isles (except Ireland) and lead to shortages of medicines and food. In an announcement reminiscent of a looming civil emergency, the UK Government has placed 3,000 armed forces personnel on standby. Yesterday, a drone scare effectively terminated operations at Gatwick Airport, leading to travel chaos – the ripple effects of which will likely last for days. What Brexit without a Withdrawal Agreement would be like? Worse, especially for the UK.

The Way Out

The 2016 national referendum on the United Kingdom’s EU membership suffered from a range of defects, but not necessarily because of the final result per se – after all, the EU itself recognizes the right of every Member State to formally withdraw from the Union, in line with Article 50 of the Treaty of European Union (TEU). The problem was the manner in which the referendum came about and the framework that governed it. Here’s why.

Instead of being a principled decision of a Prime Minister truly convinced that it was time for the United Kingdom to leave the European Union, the 2016 referendum resulted from what can only be termed a tragicomedy of errors. You see, David Cameron (despite his repeated Eurosceptic statements during his own campaigns as an MP and as a Conservative leader) never had his heart set on putting the European question to the people. Instead, the promise to hold an In/Out referendum had been inserted into the Conservative Party’s 2015 general election manifesto (page 72, for those who are keeping score) in order to fend off a major threat from the populist-nationalist United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP). Indeed, UKIP had performed extraordinarily well in the European Parliament elections (which, ironically, they would not have if the European Union had not mandated a switch from First Past the Post to the proportional representation electoral system) – and was threatening to slice off enough Conservative voters in the 2015 general election to cost Cameron his post as prime minister.

Cue the promise to stage a national referendum on the United Kingdom’s EU membership – which Cameron may very well have hoped he would never have to keep. Bear in mind that at the time the pledge was made, the Conservatives were behind the Labour Party (led by former Environment Secretary Ed Miliband) and could plausibly have been expected to lose the general election. In the end, due to several missteps by the Labour Party (and Miliband proving to be a particularly unpopular and wooden opposition leader), the Conservatives won a surprise majority in the House of Commons. With Cameron forming a Conservative majority government, he was obliged to keep the promise concerning the In/Out referendum.

Uncertainties

The European Union (Referendum) Act 2015 did not specify a clear set of questions to be asked of the voters. Instead of asking a clearly worded set of questions separating the electorate’s views on the principle of leaving the European Union, and the actual method of leaving the European Union, the ballot merely asked a vague question about “remaining in” or “leaving” the European Union. Bear in mind that even the choice of words itself was loaded – with “remain” connoting stagnation, a static state of affairs and a lack of movement. “Leave” on the other hand indicated change, action and dynamism. Combined with the fact that the British people were called to vote on a vague question, rather than voting on a law or at least issuing specific instructions to Her Majesty’s Government, this resulted in a situation in which the supporters of the Leave campaign could float promises of the UK staying in a EEA/Norway-style arrangement (thus participating in the Single Market and Customs Union) and once the referendum was over, claim (without any major pushback from the broadcast media) that a mandate had been given to execute a hard Brexit. No such mandate was given.

Fanciful Notions

Besides, the franchise of the referendum was another problem – with up to a million UK citizens living across the EU27 having been excluded from the right to vote in the 2016 national referendum, the referendum itself being held in the middle of the university holidays (when turnout in pro-Remain university towns would be low) and, typically for the UK, on a working day (Thursday) – which depressed turnout. Despite the Prime Minister repeatedly claiming the national referendum to be the largest democratic exercise across the UK, turnout only averaged 72%, lower than several past general elections and also much lower than the Scottish independence referendum. Given the closeness of the result, the notion that 52% of the 72% who did vote to leave the European Union, should be able to effect a major constitutional change is rather fanciful.

Opportunities Unused

Even if that were not the case, the cold hard fact remains that the proponents of Brexit have been campaigning for this outcome for years (and in some cases, decades). That is plenty of time to propose and prepare implementing legislation. That is also plenty of time to reflect on the United Kingdom’s negotiating objectives and position during the negotiations in an intellectually honest fashion. Those advocating Leave had the choice to actually frame withdrawal in terms of a fresh start, not an acrimonious divorce – as the first phase towards the UK taking a central role in developing the European Free Trade Association as a viable alternative to the European Union, for all those Member States wary of federalist ambitions among some elected officials in Brussels, but still appreciative of the commercial benefits of trading together. The Leave referendum campaign could have been led by pragmatists, not hardened ideologues and fantasists, and with a genuinely optimistic note. After all, Article 50 TEU itself recognizes every Member State’s right to leave (with the CJEU’s recent decision in Wightman clarifying every withdrawing Member State’s right to revoke the Article 50 notification unilaterally, prior to the withdrawal becoming effective). Instead, Leave chose campaign tactics imported from across the Atlantic to demonize Remain supporters and thus fractured the political cohesion necessary to obtain a good negotiating result from the EU27.

Poisoning the Mood

The Prime Minister failed to discipline key ministers threatening the EU27 via the media, and thus witnessed any goodwill the EU27 might have had towards the UK being frittered away. It is evident now that Theresa May’s deal is dead. It is also clear that there is no parliamentary majority for a hard Brexit. It is also clear that Brexiteers have had a full two years to make the democratic mandate conferred by 52% of the 72% participating in the advisory referendum work. They have failed to do so. If anything, Brexit is emblematic of a failure of leadership on part of Prime Minister May, the Brexit faction within the Conservative Party and (crucially) also the shambolic leadership of opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn – who is defying his own Labour Party’s stated policy to prevent a second referendum for as long as possible, since he himself is a thinly veiled Eurosceptic himself. The result is an impasse, with the UK approaching the precipice of a No Deal scenario.

Return to the People

The way out is to return to the British people and seek a fresh set of instructions in a second national referendum. Despite the claims of the hard right, the will of the people is not static and democracy does not equate to blindly executing a mandate that was given in the absence of reliable information – and a lack of knowledge about the concrete consequences of the decision. Following the Article 50 process, the United Kingdom had been given a generous opportunity to demonstrate the soundness of its negotiation strategy. Brexit advocates could have shown that their assumptions about the intentions of key EU Member States would be right. But instead of putting their car industry first, Germans opted for the integrity of the Single Market. The French care more about the European project’s long-term viability than champagne sales. The Brexiteers were wrong because they did not want to face the facts. The facts are clear – the Prime Minister has tried to secure a favourable deal. She has not done so. The assertion of Brexiters that the 2016 referendum result in which a bare 37% of the eligible electorate voted to terminate the country’s EU membership has to be implemented, no matter the cost and the disruption to the country’s economy and its people is not just irresponsible, but disrespectful of the very citizens they claim to speak for. These people have the right, like in any democracy, to change their minds – to deny them the right to issue fresh instructions, that is the ultimate sign that the Leave advocates see democracy as a slogan, not a principle to be lived by.

Second Referendum Mechanics

How could a second referendum happen? Whilst there are many proposals out there, let me add my two cents: Given the Prime Minister’s defiance, Parliament itself (maybe centred around senior figures in all parties) would have to take charge by passing a new European Union (Confirmation Referendum) Act. Such new legislation, which could use many (but not all) parts of the European Union (Referendum) Act 2015 as its template would do several things the 2016 referendum did not: first, provide a clear set of questions to be asked. Second, provide for the referendum to be legally binding and mandate automatic steps to be taken upon a certain result prevailing; third, take measures regulating equal airtime and social media campaigning – something that was a major problem in 2016; fourth, mandate a request regarding extension of Article 50 by the United Kingdom Government and fifth, expand the electorate to include the British citizens living in the EU27 whose rights will be affected by the referendum result.

The referendum ballot should ask three questions:

Question 1 would ask about Theresa May’s deal in the following terms:

“Do you wish to give Her Majesty's Government the mandate to execute the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union under the terms of the Draft Withdrawal Agreement of 15 November 2018? YES/NO”

Question 2 would ask voters what they wish to do in case May’s deal fails to get a majority:

“In the event that the majority of voters does not give a mandate to Her Majesty's Government to execute the withdrawal under the terms of the Draft Withdrawal Agreement, do you wish for Her Majesty's Government to remain in the European Union? YES/NO”

Question 3 would ask voters what were to happen if both May’s deal and the Remain option were voted down:

“In the event that a majority of voters does not authorize the Draft Withdrawal Agreement or continued membership of the European Union, do you instruct Her Majesty's Government to negotiate and execute a withdrawal from the European Union under the following terms?

- Leave the Single Market YES/NO

- Leave the Customs Union YES/NO

- Leave the European Atomic Energy Community YES/NO”

Such a referendum would enable a clarification of the will of the British people, enable their informed consent to either of the options enable them to make their final decision in light of all the potential consequences they could not have been aware of prior to the withdrawal negotiations beginning. Democracy does not end with an election or a referendum. It is a continued process. Given the impasse and the failure of leadership in Westminster, it is time to put faith in the voters making a fresh decision – and then carry out the result with clarity. At this time, it is the only way out from the risk of a major precipice. Time for the adults in the room to take charge.

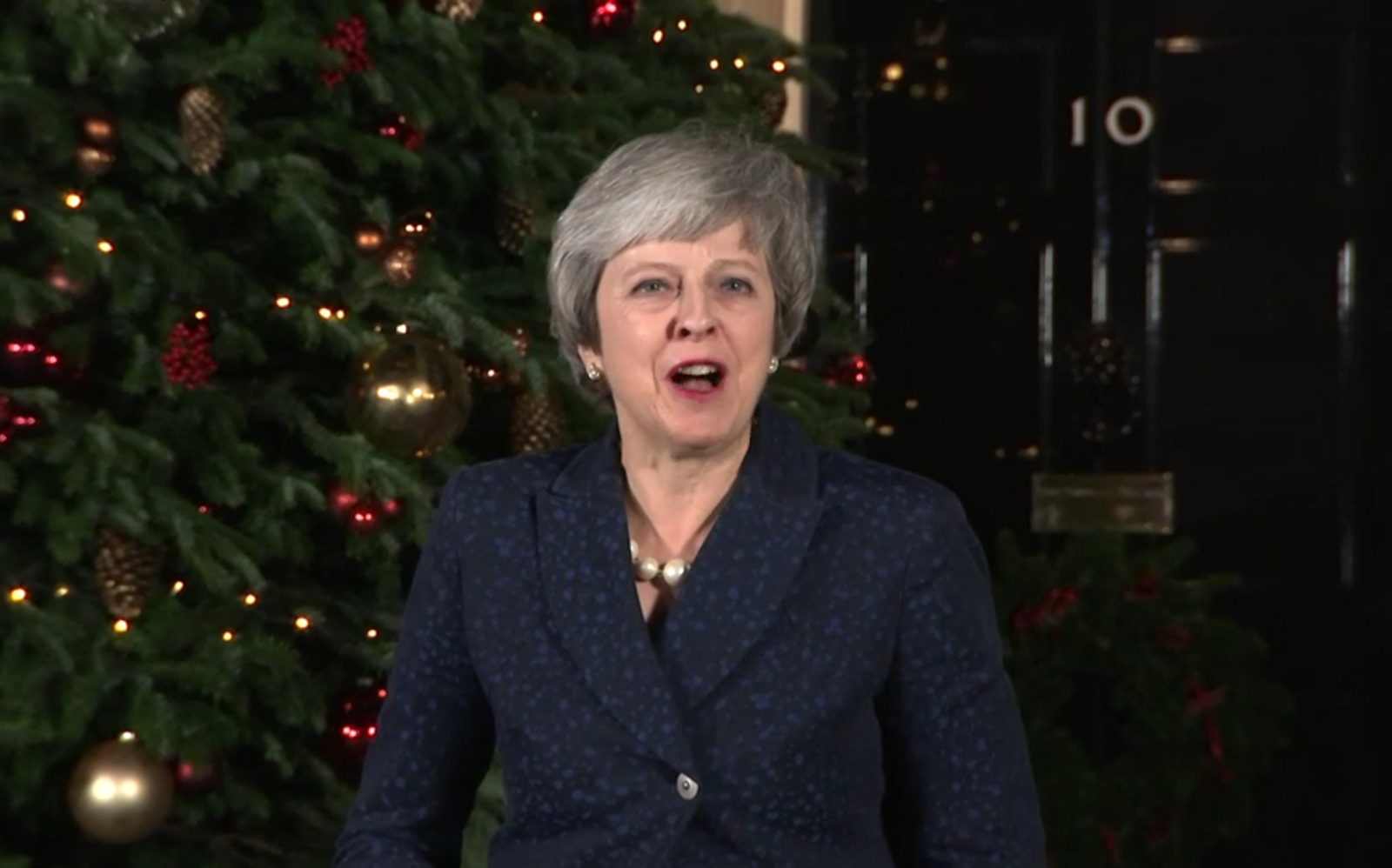

Images by Flickr, image Theresa May by Tiocfaidh ár lá 1916 and image UK flag by Elliott Brown

| More blogs on Law Blogs Maastricht |